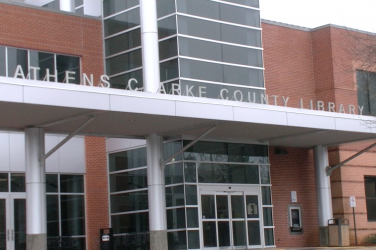

The public defender’s office for Athens-Clarke and Oconee counties handles thousands of cases in a given year, but the overwhelming majority of those cases will never see the inside of a courtroom.

Most cases are resolved through plea bargaining, a process in which the defendant agrees to plead guilty in exchange for a more lenient sentence or reduced charges.

In some situations, prosecutors will agree to drop charges in exchange for the defendant’s testimony in another case. If there are multiple charges, a defendant could plead guilty to have other charges dropped.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Jury trials can take months or years. Plea bargains make the courtroom more efficient, but it can push people to plead guilty even when it is not in their best interest.Around 90 to 95 percent of federal cases are resolved through these agreements, according to a report by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA).

Circuit Public Defender John Donnelly said the number of local cases that end in plea bargains is the same. “More than 90 percent,” he said.

Donnelly, 55, works at the Western Judicial Circuit Public Defender Officer, which handles cases from Athens-Clarke and Oconee counties. The office covers juvenile, traffic, misdemeanor and felony cases. Judges will appoint public defenders to represent people who cannot afford them.

The popularity of plea bargains in the United States grew in the late 19th century and early 20th century, according to a journal article by Albert Alschuler, a professor of law and criminology at the University of Chicago.

Alschuler writes that in 1908, half of federal cases ended with a guilty plea. In 1916, it increased to 72 percent, and by 1925, the number was almost 90 percent.

Similar numbers were found in surveys of states and cities during the 1920s, according to Alschuler.

Incentives to Plead Guilty

The rise of plea bargains coincided with the growing complexities of jury trials and the expanding length of trials, said Edward Brumby, staff attorney under Judge Lawton Stephens.

The system would come to a halt if every case went to trial,” said Brumby.

Brumby, 65, from Murphy, North Carolina, has worked as a prosecutor for the district attorney’s office for Athens-Clarke and Oconee counties and worked 13 years as a public defender in Athens.

“The system is structured such that it can be very disadvantageous for a defendant to go to trial,” Brumby said.

The length, financial burden and risk of trials can incentivize defendants to accept plea deals. For people who cannot afford to post bond and cannot miss work for an extended time, pleading guilty may be their only option.

“One reason that sometimes people will agree to a plea is that because they are in jail, and the only way they’re going to get out is by pleading to it, unless they’re going to wait for their trial, which could take a year,” Brumby said.

Defendants also have to consider the unpredictable nature of trials. There is no guarantee that a jury will take their side. The BJA report found that defendants that go to trial are more likely to receive harsher sentences.

Occasionally, defendants will accept plea deals even if they are innocent.

There has been a recent increase in exonerations of cases where the defendant pleads guilty, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, which analyzes all known exonerations of innocent criminal defendants in the United States.

From 2008 to 2013, there were 60 known guilty-plea exonerations, an average of 12 a year. There were 74 exonerations in 2016 alone.

“I had clients who maintained their innocence and may have been innocent, who ultimately decided to plead guilty because of the consequences of what the sentence would be after trial as opposed to what was being offered them in plea,” Brumby said.

Public Defenders are Underfunded

Contributing to the prevalence of plea deals, public defenders across the country typically do not have the appropriate number of attorneys to meet the guidelines provided by National Advisory Commission’s (NAC) numeric caseload standard.

Three in four county-based offices did not have sufficient staffing and nearly a quarter has less than half the necessary attorneys, a press release from the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported in 2010.

Staffing is not a major concern for Donnelly here in Athens. He has worked in the county for 30 years and handles serious felony crimes like murder and rape.

“I think the governments in this jurisdiction are appropriately funding us,” Donnelly said. “We could always use more attorneys.”

Athens public defenders are under the maximum number of cases for misdemeanor and felony cases compared to the NAC standards.

The four lawyers assigned to state court, which handles general misdemeanors, would have more than 100 open cases at any given time, Donnelly estimated.

An attorney should not handle more than 400 misdemeanors per year, excluding traffic cases.

The eight superior court lawyers, who handle felony cases, would have similar numbers, but their load is smaller, said Donnelly.

An attorney should have no more than 150 felonies per year.

Prosecutors Have More Power

While the public defender’s office may seem to match the resources of district attorney’s office, it covers more courtrooms and has comparatively less staff in felony cases.

The DA’s office is responsible for prosecuting felony cases in Athens, while misdemeanor cases are handled by the solicitor general’s office, according to Chief Assistant District Attorney Brian Patterson.

This imbalance can be observed in the courtroom. The defense team has two attorneys while the prosecution has three.

Ideally, I think that if there are going to be three prosecutors in the courtroom, there should be three public defenders,” Brumby said.

The relationship between public defenders and prosecutors is adversarial in nature, and while the offices are cooperative and professional in Athens, there is still lingering tension.

“What I think is a bigger issue is prosecutors filing and charging cases that they probably can’t prove. That happens too often in my opinion,” said Donnelly.

In February 2018, 30 criminal cases came before Judge Lawton Stephens in the Superior Court. Twenty-eight of those cases were resolved through plea deals. Two cases were jury trials. Only one came back completely not guilty.

Patterson, who has worked as a prosecutor for 22 years, thinks the adversarial system works effectively.

“I think it’s the best system in the world,” he said. “It’s not perfect. Resources is the biggest issue.”

Patterson, 47, from Cobb County, explained that the DA’s office under the direction of Ken Mauldin evaluates the evidence presented, the defendant’s criminal record, the victim’s wishes and other factors when deciding whether to prosecute a case.

“I worked for Mr. Mauldin,” Brumby said. “There was quite a bit of discretion, and so usually when you went forward on a case, it was because you believed it was in the interest of justice.”

Whitley Carpenter is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, English in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences and is pursuing a master’s degree in English at the University of Georgia.