Where: Science Library on South Campus

When: Nov. 30-Dec. 16

Off campus:

Where: Creature Comforts

When: Dec. 18-Jan. 27

Delicate molecular models rest on the window sill of Yohanna White’s one bedroom apartment, catching the light and casting a shadow of webs onto the crown molding. Miniature dragons and air plants are carefully balanced on the beams and elbows of the models, creating a sort of medley of science and art in her home.

White has never been particularly artistic herself, but she has an appreciation for the eclectic and demonstrates her love for both art and science through these tokens on her window sill. Before now, White existed in a catacomb of mostly science. She works as a computational chemistry student at the University of Georgia and spends most of her time interacting on a highly science-oriented level.

That began to change after White received an email inviting her to collaborate with a print maker in an effort to translate science into art. White was instantly intrigued by the goal of this project, the Head and the Art, which is an art exhibition organized to pair artists and scientists together to show the possibilities of art and science collaboration.

“I think people like to think of art and science as separate ends,” White said. “A lot of people in science say they can’t do art and a lot of people in art say they can’t do science. So I feel like that’s why there hasn’t been a lot of collaboration between the two.”

Megan Prescott and Taylor Newman, science-grounded graduate students at the University of Georgia, felt the same as White, and they wanted to shrink this divide.

Why It’s Newsworthy: A new wave of cross-disciplinary collaborations among the humanities and sciences is beginning to spread. Wisconsin Institute of Discovery and Harvard pioneered the catalyst for this academic medley, with the University of Illinois following close behind. Prescott and Newman are bringing this collaboration to UGA through the Head and the Art science and humanities alliance.

The array of artists participating include sculpting, metal working, painting, a tattoo artist, weaving and even a solo performer who is both a dancer and a scientist. The scientists study topics ranging from hard to soft sciences, including entomology, disease ecology, genetics, forestry and psychology.

“I think a lot of times people think that people in the arts and people in the sciences are very different and that there’s no way that there could be a collaboration or a desire on the scientists to do something different,” Newman said.

Cross-Disciplinary Outreach

In the Head and the Art, the artists are given the power to pick to which scientist they are most drawn. The artists use their talents to interpret the scientists’ field of study through their medium of choice, while the scientists are challenged with explaining their practice to the artist, and in turn, to the viewers of the exhibition.

Strategic outreach is at the heart of this exhibition, and a key audience is the high schoolers within Athens-Clarke County, along with college-age individuals. In addition to the education through the art exhibition, Newman and Prescott will visit Clarke Central High School to teach students how to create pigments for art through traditional chemistry processes. Any art these high schoolers create can be showcased at the exhibit as well.

Both Prescott and Newman largely exist within the science community exclusively. They both see firsthand the void of science and art collaborations. Seeing this void drives them to emphasize making the sciences more accessible for all interest groups through the Head and the Art.

I feel like, especially in this day and age, there is a lot of miscommunication about science and the best way to reach people for me is to talk to people directly and talk to people not normally interested in science so they can get that interest on their own,” Prescott said.

Within the science community itself, educational outreach is modeled in a vacuum, Newman and Prescott said. When outreach is structured, it adopts a language often only understood by other science-minded people. This hinders others from understanding even the most conceptual of ideas because the language used to describe these concepts is elevated to an exclusive level.

“I know some people try to outreach to the community about science but it is still just showing people a science display,” Prescott said. “It may be in layman’s terms but it still approaches it in the traditional ways of explaining science, whereas we are trying to approach it as, ‘This is art.'”

Newman and Prescott are striving to overcome this hurtle with creative outreach. Prescotts’ inspiration to kindle this marriage came from a Carl Sagan quote saying that both arts and sciences use creativity, problem solving, innovation, experimentation, to display some kind of truth or understanding.

“Science does this by making the invisible, visible and art makes the unknowable, unknowable and when you combine the two of those you can visually express a concept that people may not have access to otherwise,” Prescott said.

Marrying the Participants

In contrast to the perception of the science community communicating in a bubble, Prescott and Newman were surprised to see the art community already reaching across the divide. It is not uncommon, they found, to see artists participating in social commentary on scientific topics like global warming and colony collapse.

Yohanna White, a Ph.D. student studying computational chemistry at UGA, is excited for the opportunity to collaborate with artists through this exhibition.

While there is a shortage of outside communication within the science community, White finds this exhibition an opportune breaking point to push past these barriers.

White looks forward to seeing how the artist interprets her work. Explaining her work to the artist was the biggest obstacle for White, as she has never been asked to communicate about her field in such detail to someone outside of a science-based field. She sees this exhibition as a growing experience for not only her own understanding and communication, but the viewer’s understanding as well.

“It’s a very unique experience to me,” White said. “Just even explaining to [my partner] what I am doing, you get to practice your science communication and I get to learn something from her. It opens up both of our worlds.”

For Nicole Solano, participating in this exhibition is a way to make both her art and her science accomplishments visible. With a Bachelor’s in dance, Solano is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Ecology. While these subjects seem to be on opposite ends of the spectrum, Solano finds linking commonalities between the two to be a natural process.

Solano will perform alone, combining her science background with her dance background to produce a choreographed dance depicting her research in mosquito borne diseases. She intends to portray the life cycle of the mosquito through dance, while showing how the environment may affect the decisions these insects make along their arc of existence.

Nicole Solano is trained in dance and is earning or working toward a Ph.D. in Ecology. Marrying arts and sciences comes naturally for her, and she will be performing a solo dance performance.

The divide between the arts and science is not foreign for Solano. Most of Solano’s fellow dance students also had a second major or minor in a hard science like biology. As a result, it was not uncommon for Solano to produce commentary on science related topics or theories through dance like circadian rhythms, for example.

“Ecology is the interactions of an organism and its environment and so for me that’s like dance,” Solano said. “There’s emotions, there’s life events, sometimes we dance for celebration, for healing, for social commentary, but its always how a dancer perceives something, so how they interact with an idea or their environment.”

Solano thinks the disciplinary divide is rooted in misconception as well. This misconception that each subject is on opposite poles is ingrained in our education system and makes blending the two poles nearly impossible, she said.

“Science is seen as something more disciplined and something more rigid,” Solano said. ” It’s a lot of having to choose between one or the other. If we were to do a better job in the education system of incorporating both, it will be something that people continue to think about and realize aren’t so different.”

Gender Participation

An interesting element concerning the participants is their gender: Everyone is female. While this was not intentional, Prescott and Newman said they are not surprised to see the interest primarily from women.

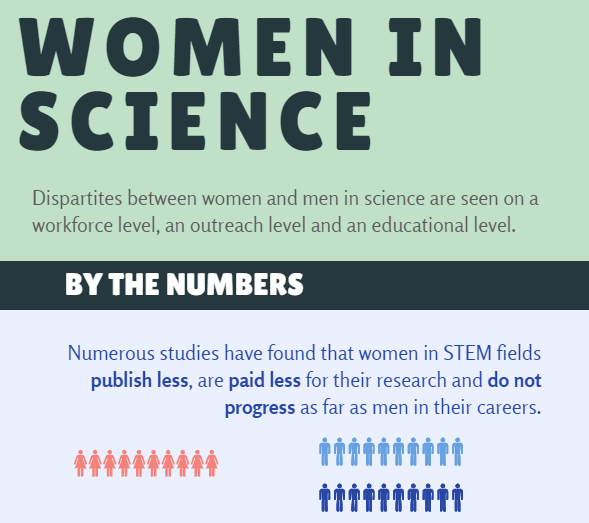

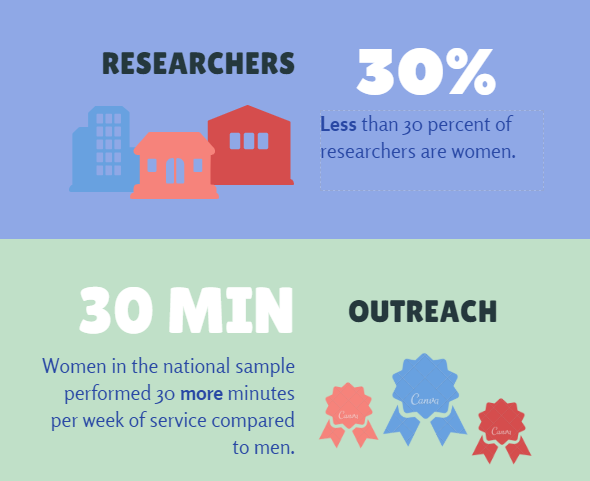

There is a disparity between men and women in the science field and workforce in multiple ways. Women make up half of the total U.S. college-educated workforce, but they make up only 29 percent of the science and engineering workforce. To break this down further, 35.2 percent of chemists are women and 11.1 percent of physicists and astronomers are women. Despite this, women do statistically more outreach than men in these same fields.

According to a study published in Higher Education that pulls data from a 2014 Faculty Survey of Student Engagement, women scientists exert more energy more in certain areas. They spend more time performing service activities and put more effort toward science communication that advocate for the advancement of the collective.

Women in the national sample performed 30 more minutes service a week compared to men, and 1.5 more service activities per year than men when measured on the local sample. What the author of this study, along with the women who organized the Head and the Art event concluded, is that the study raises questions about gender-based incentives, and individual versus collective reward.

While women strive to advance the institution’s collective outreach mission, having all women participate in this collaboration didn’t take the organizers by surprise.

“A lot of people think publishing your work in a scientific journal is a way to get your work out there but the only people who read your stuff in scientific journals are other scientists,” Prescott said. ” This is another avenue to make scientists’ work more visible.”

Campus and Community

The exhibition will be displayed in both an on campus location and a community location. The art will be displayed in the Science Library on South Campus from Nov. 30-Dec. 16. Following the on-campus exhibition, the art will relocate to Creature Comforts from Dec. 18-Jan. 27.

Newman and Prescott were intentional in choosing the Science Library because they wanted a space where individuals of all majors could see the exhibit without needing to intentionally seek it out.

White hopes that this exhibition not only promotes the marriage of these subjects to the college-aged viewers who frequent the Science Library, but to younger children as well.

“I hope that viewers would see that there is more of a bridge between art and science and that they have a better appreciation for both, not just one over the other,” White said. “It doesn’t have to be this or that, you can like both. I hope people, especially younger kids, can learn to like both.”

Finding a harmony between the arts and sciences starts with the seed of an idea that is driving the organization of an art collaboration, and can be seen spreading from high institutions like Harvard to the local level like Clarke Central. These two subjects are only as separate as curriculum will make them, and marriages like the Head and the Art are beginning to bridge this divide.

Maggie Holland is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.