Jasmine Best grew up in the hills of North Carolina watching her grandmothers and great grandmothers sew and crochet — which led her to develop an interest in the craft.

“It’s kind of recontextualizing the women who taught me these skills or had to use these skills and putting it into a context they never would have dreamed of,” she said. “I don’t think any of my grandmothers or great grandmothers ever would have thought of their sewing work or their crocheting work being in a gallery space, which would have been kind of blocked off to them.”

Now an artist specializing in fabrics and textiles, Best is a first-year MFA student at the University of Georgia. Some of her artwork that focuses on Black identity and womanhood in the South is currently displayed at Lyndon House Arts Center, making it one example of the uptick in representation of Black artists in museums and galleries since the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the United States in 2020.

Best said that she’s noticed this increase, and while it is great to have more representation, she believes not all of it has been genuine.

“I think right now is an interesting time to be a Black artist or a marginalized artist. I think there’s definitely been an increase in grants and certain residency opportunities and funding,” said Best. “I think there’s kind of a flipside to that where there has been this practice of tokenism. I know during 2020, everyone was in a mad scramble whether it was a museum or a corporation to just capitalize on Black voices.”

More Inclusive Workplace

Best added that there needs to be more work done to diversify the administrative aspect of the art world.

“I don’t know if we’re seeing as much of the board members being changed, maybe looking into who’s funding these things or who is working,” she said, “What’s the hierarchy structure of who’s running the museum?”

Didi Dunphy, program and facility supervisor at the Lyndon House Arts Center, also said there needs to be more diversity in the different branches of art “whether it’s an exhibition of an artist hanging on the wall or a staff person, specifically people in higher ranking positions in the art world.”

She said this kind of work can be difficult and takes time.

“In our experience here, you can’t just like flip a coin and ‘oh we have full representation.’ This is a long-term investment,” said Dunphy, who said that effort has to extend beyond the conference room.

“You have to put it front and center. You cannot just wait around for something to happen. Many cases you need to go to the community. You need to reach out. You need to build your relationships outside of just your meeting area,” she said.

According to 2019 Census data, an estimated 24.7% of Athens-Clarke County’s population’s racial makeup is Black, which Dunphy said is important to take into consideration when curating exhibits that represent the people that live in the area.

“When we are designing programs whether that is in education or in exhibition or in outreach or in professional practice, the first question that I usually ask the team is ‘where are the people of color in this equation?’” said Dunphy.

Changing Narratives of Southern Art

While representation has risen in gallery spaces, Best said there also should be more work to examine the experiences of Black artists.

“What is Southern visual arts? Southern contemporary art?” she said. “The answer is really clear when it comes to what is Southern food, what is Southern music, what is Southern literature, but for visual art it’s not as clear.”

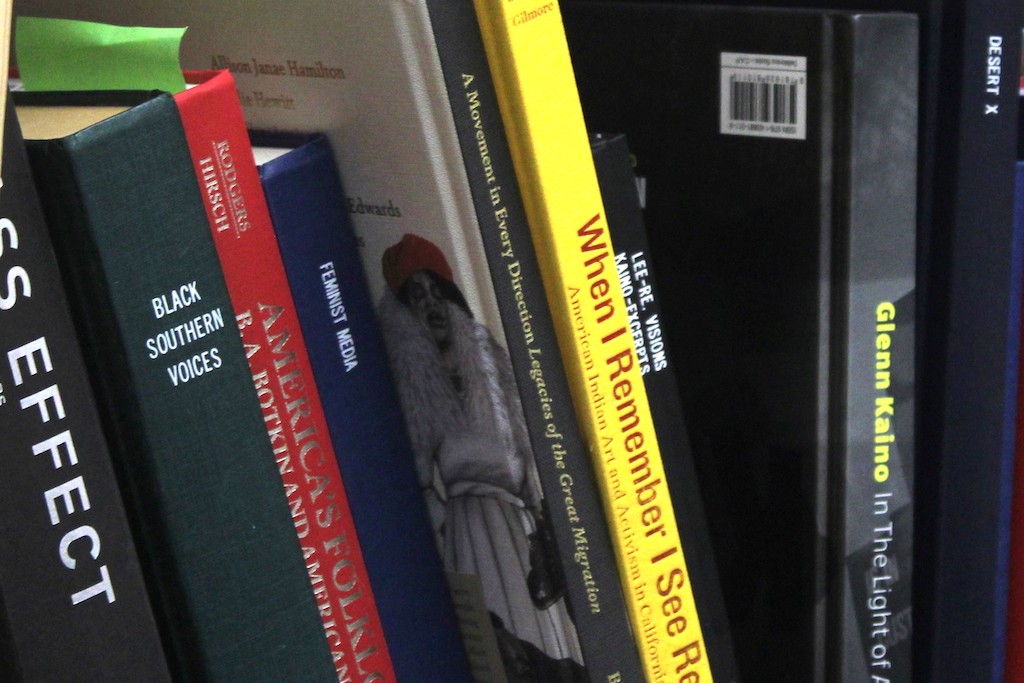

She has seen narratives that focus on the artists who moved to the North during the Great Migration, but not as many from Black artists who stayed in the South.

“I think being Southern is something bigger than preferring a certain kind of food or the way you talk,” said Best. “I think it’s acknowledging the legacy that slavery has below the Mason-Dixon line because if it affects everything from the way streets are named or the way the infrastructure of a city is held or the education of a school district, then it must affect the people who live there.”

She said Black art should not have to focus solely on racial issues either. Best said, “They are allowed to do things that their non-Black counterparts are allowed to make freely without really questioning it.”

Best said it is an integral part of art to create diverse perspectives.

“The more viewpoints or cultural viewpoints that people have, I think the better their lives will be, the more rounded,” Best said.

Julianne Akers is a fourth-year journalism student at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)