A perfectly curated photo begs to be shared. In a millisecond, with the click of a mouse, a human commands a computer to upload the photo to the internet. The computer displays a loading symbol, but no signs of progress. The photo might finish uploading in the morning, but the user can’t be sure.

This is the process of uploading a picture to the internet as experienced by Madison County resident John Graves. He and other county residents are familiar with the inconveniences of slow internet or complete absence of broadband. Their accounts vary greatly from that of the average internet user.

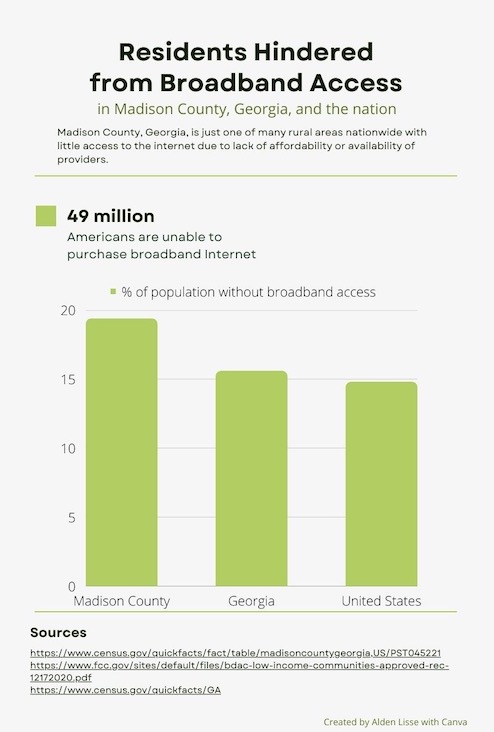

Why It’s Newsworthy: Limited access to broadband connectivity mostly affects residents of rural communities, not just in Madison County, but across the state of Georgia and in other parts of the nation, as well. High-speed internet is essential to the fields of education, healthcare and employment, but 14.8% of U.S. households don’t have a broadband subscription, according to U.S. Census data.“If this past year has taught us anything about our infrastructure, it is that current broadband Internet access is insufficient to reach all of our communities,” U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde said in an email. “Nearly every American has relied on high-speed internet to continue their day to day lives, but unfortunately, way too many of us have experienced significant connection issues that have hindered our productivity.”

Loss of Opportunity

A hindrance to productivity is exactly how Kerry Godfrey describes the broadband issue’s impact on sales at her farm, The Naked Farmer, which she runs with her fiance, John Graves. Their farm’s website features an online store, where the couple sells their products to customers nationwide.

“The Naked Farmer is an e-commerce,” Godfrey said. “That’s how it started. And because COVID was really, really good to us… to have reliable internet is everything.”

The increase in online shopping brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic helped the Naked Farmer grow 600%, according to Godfrey. However, the couple is waiting to expand into a Madison County storefront as soon as their area receives adequate internet service.

So it’s blocking us from being able to be more productive because you can’t have a storefront and not have internet… It blocks us from growing,” Godfrey said.

Graves, who has had the same provider since he purchased an internet subscription for the first time in 1998, ssaid he has paid more every year for the same internet speed. At his home in Commerce, Georgia, Graves said he can download something from the internet at a rate of 1.6 megabits per second. In the United States, the median fixed broadband download speed is 159.31 Mbps, according to the Speedtest Global Index.

Graves lives on one of the busiest roads in the county, according to traffic count data from the Georgia Department of Transportation. How could high speed internet not reach Madison County’s busiest road? Graves’ internet issue isn’t an anomaly in the county. According to the newly published Georgia Broadband Availability map, 37% of Madison County is currently considered unserved by broadband services.

“There are people that have farms that don’t have internet… There’s residents and some farmers that don’t have it, and they don’t have a choice,” said Graves. “So a lot of them use their cell phone or hotspot. That’s not reliable. And it’s expensive.”

Mapping the Problem

Broadband availability data from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) previously underestimated the number of unserved counties in Georgia. A recent revision of this data revealed approximately 10% of Georgians have little to no internet service, according to Eric McRae, the associate director of the Carl Vinson Institute of Government at the University of Georgia. The new map, produced by McRae and his team, considers an area unserved where 20% of homes and businesses can’t access the standard broadband speeds of 25 Mbps downloads and 3 Mbps uploads, according to the Georgia Department of Community Affairs.

The bulk of Georgia’s unserved locations tend to be rural counties, according to McRae. He says the cost of expansion to rural areas sometimes outweighs the return on such an investment for internet providers. Federal funds to cover these costs are being distributed to providers, but smaller communities are dependent on their local governments to receive such funding.

“These locals should reach out to their local leaders to basically, you know, encourage them that they do in fact want broadband,” McRae said.

Political Push

Broadband access has been addressed on local and national levels by politicians such as representative Clyde and Sen. Raphael Warnock. To address this issue in Madison County, Clyde introduced H.R. 5512, the Reviewing and Updating Regional and Local (RURAL) Broadband Mapping Act in 2021.

The bill would temporarily allow states to use their own statewide maps, which would represent broadband coverage more accurately. These state-developed maps could help identify broadband scarcities until the FCC updates its national map, as required by the DATA Act signed by former President Donald Trump in 2020.

Federal funding will help expand broadband access to unserved areas, but the expansion process takes time. If passed, Clyde’s bill would serve as an interim solution until the FCC can completely correct its map.

In the meantime, government programs have been approved to fund providers’ expansion to unreached areas. Madison County has been approved for the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), a $20.4 billion FCC initiative to bring broadband to unserved areas.

“I mean, it’s a waiting game,” McRae said. “But I mean, there is a light at the end of the tunnel where things are being built out. I know that there are fiber deployments all over Madison County, and they’re continuing to build.”

Alden Lisse is a senior majoring in journalism with a minor in religion at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)

Perpustakaan Online

How has the lack of reliable broadband in Madison County hindered the growth of local businesses like The Naked Farmer, and what specific infrastructure challenges have residents faced?