CORRECTION: Jenna Jambeck, Ph.D, and Kyle Johnsen, Ph.D, are not University of Georgia graduates. They both graduated from the University of Florida College of Engineering. Grady Newsource regrets the error.

Take a walk around your neighborhood: maybe to the closest busy intersection, maybe on the trail behind your house. What do you see?

Likely, litter. Nearly eight billion people inhabit the Earth, so it’s difficult not to become desensitized to the growing presence of chip bags, plastic bottles and cigarette butts along roadways, sidewalks and even out in nature.

But what if there was a way to track the amount and type of litter we see – to quantify the problem and eliminate the possibility of desensitization?

The Marine Debris Tracker (MDT) has been legitimizing that idea since 2011, and local players like litter abatement organization Keep Athens-Clarke County Beautiful are furthering the app’s influence in Athens a decade later.

The Marine Debris Tracker

The MDT is a database of litter concentrations in localized areas fueled by citizen science. It was created by Jenna Jambeck, Ph.D, and Kyle Johnsen, Ph.D, both graduates from the University of Florida College of Engineering and now professors at the University of Georgia. Their vision for the MDT app is to give citizens a tool to log the amount, type, brand and other characteristics of litter they find on organized cleanups, or just walking their dog. By logging this litter, Jambeck hopes to better understand how types of litter in certain locations can show what environmental efforts are needed in that area.

Why It’s Newsworthy: As responsibility to keep the Earth clean falls more and more on citizens alone, an app that quantifies the user’s positive impact on the environment while contributing to a larger database can help us understand the power of individual action.

Taylor Maddalene, the Director of the Circularity Assessment Protocol (CAP) at Jambeck’s Circularity Informatics Lab at UGA, said a simple way to determine what environmental services a city is missing to control litter is by first turning to science.

“This kind of data will inform what’s working and what’s not and will be an easy way for cities that have implemented things like [plastic] bag bans to see clearly if that translates to less litter,” said Maddalene.

Nearly four million items have been logged in the app since its creation. CAP uses this database to research litter abatement and more. The data is open source, so anybody researching this plastic pollution problem can access it via the MDT website. Organizations can even create their own lists in the database that encompass only the items from their cleanups to make visualization easier.

A Circular System

Understanding “what’s working and what’s not” means finding out what types of litter are escaping the circular system of the waste stream. That’s right: circularity isn’t just an economic buzzword, but an environmental solution. Without litter, every output in a waste stream goes back into an input, creating a closed loop where no waste escapes onto roadways and into nature.

“When patterns start to emerge, you can understand why things are escaping a waste management stream,” which is the primary goal of MDT, Maddalene said.

Litter items may escape the waste stream because they’re too lightweight and are blown out of the system. Local options to recycle that item could be lacking, or there could be too few public waste bins or household collection services. These are localized environmental needs that can be determined by studying the circularity of waste through MDT.

For example, nearly half of plastic produced is lightweight plastic packaging, which largely consists of single-use items intended to be used for 10 minutes and then thrown away, said Maddalene, former Director of the Plastics Initiative for the National Geographic Society. Most of those items cannot be recycled, creating a very linear waste chain.

“The idea with circularity is that you don’t have that, ‘create it, use it once, discard it’. You either create things that are durable and reusable or you create something that can be repurposed, recycled efficiently,” Maddalene said.

Enter: Keep Athens-Clarke County Beautiful

But who are these citizen scientists collecting circulatory data for MDT?

They’re average people, many of which make up organizations like Keep Athens-Clarke County Beautiful (KACCB), an affiliate of Keep America Beautiful (KAB) housed in the Athens-Clarke County Solid Waste Department, whose goal is to empower citizens and businesses to implement litter abatement and beautification strategies in their communities.

“You want to be proactive about litter,” said Stacy Smith, the Program Education Specialist for KACCB, “We don’t want to always be picking it up, we want to understand what’s going on and get it before it flies out the window or gets dumped.”

Smith knows a tool is only as good as its application, which is why in April 2021, the nonprofit partnered with The UGA Office of Sustainability for the UGA Earth Day Global Community Cleanup, a campus-wide effort to pick up as much litter as possible the week of Earth Day.

Through the “Keep Athens-Clarke County + UGA” list on the MDT app, all parties involved collected 870 debris items in that week across a total 579 cleanups, primarily around campus, according to MDT datasets.

Kira Hill, a third year genetics and psychology student at UGA, used the app for the first time during the cleanup. She said that digitally quantifying the endless amounts of litter she found on trails behind her Athens apartment added to the triumph she feels from physical cleanups alone.

“For me the impact is when I can step away from the site and say, wow, that looks so much cleaner,” said Hill.

Like Hill, KACCB isn’t new to litter cleanups, just digitally tracking them.

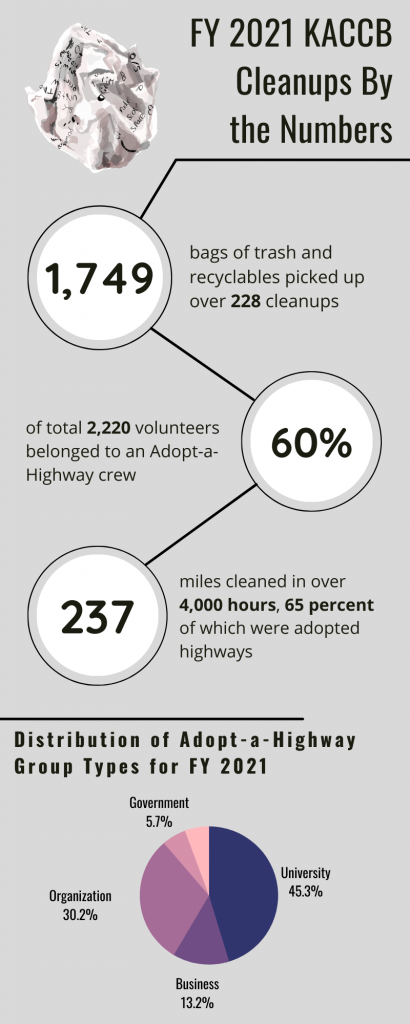

As of this year, they manage 78 Adopt-a-Highway groups across the county, 53 of which held a cleanup this year. Their total 101 groups collected 1420.5 bags of trash and 328.5 bags of recycling over 237.29 miles of ACC roads this year, according to KACCB cleanup data.

A Deeper Litter Index

However, these preexisting groups are slow to make room for MDT in their quarterly cleanups, so KACCB searched for ways to expand the success of the Earth Day cleanup into their everyday operations.

All KAB affiliates must track litter in a yearly litter index. In each commission district of ACC, six roads are chosen and driven down once a year to visually determine how littered they are on a scale of zero to four – zero being most clean and four being the level of illegal dumping.

The problem with the litter index? While it gives KACCB a general idea of which areas of the county are most littered, the information provided is too vague to be actionable. Further, many of the litter index sites aren’t centrally located in Athens, meaning few cleanup groups favor trash grabbing there. KACCB needs physical cleanups that show how different types of litter are concentrated in certain areas if they want to understand how to turn level four sites into level zero sites.

“A lot of the roads we know have major issues happen to be the ones that are maybe a little further out of everybody’s way,” said Smith.

On top of that, the COVID-19 pandemic put much of KAB affiliate duties on hold, including reporting the annual litter index. With this new freedom, Smith said KACCB was able to step back and do something different.

Moving Forward

So KACCB turned back to MDT. Within the app, they added “target survey areas” for users in their list to see which areas are in higher need of a pick up. These basically correspond to the six old litter index sites in each county district.

KACCB plans to encourage use of these target survey areas by organizing quarterly cleanups at them where tracking via the MDT app is the priority. Preexisting events where this structure could be implemented include another Earth Day campus cleanup, the annual Rivers Alive waterway cleanup and potential event to fall during KACCB’s regular yearly litter indexing time.

“The information obtained just passively with the app being out there and people using it is a lot of good information. And then being a litter abatement organization, being more systematic about it would be awesome,” said Smith.

As of now, KACCB hasn’t yet reported these MDT findings to KAB, and there’s a possibility that KAB will continue requiring only the nationwide zero-to-four litter index surveys. In this case, KACCB will boil their MDT data down and report the index as they always have.

“But we will have more specific information about the litter in our community,” said Smith.

The app itself is constantly being reevaluated for updates that make it more user-friendly and easy for students like Hill to use on a walk around town, said Maddalene.

“The intent with these kinds of free, open source, widely available citizen science tools is putting as much data in the hands of the people that have the ability to affect change, and doing that in a way that’s easy for them and meaningful,” said Maddalene. This is what Jambeck’s Circularity Informatics Lab at UGA is constantly working towards.

So, maybe next time you take a walk and see a plastic bottle or scrap of metal, you’ll pull out your smartphone and get tracking.

Reed Winckler is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and minoring in anthropology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)