It’s easy to miss the entrance to the Orange Twin Conservation Community. About 15 minutes north of downtown Athens, Georgia, it takes a couple of country roads off the highway and a keen eye to spot the welcome sign, hidden behind a layer of overgrowth.

Once a space thrumming with the energy of 2000s punk bands, Orange Twin has a different atmosphere now. Crowing roosters and barking dogs have replaced what might have been the sound of bassist and percussionists 20 years ago. Laura Carter, band member of Elf Power, is the only person living in the five-bedroom house now.

“We had 10 shareholders when we purchased the land,” Carter said. “Immediately after purchasing the land, we were offered this house to move; it was going to get demolished.”

This was back in 2000, when Carter, some bandmates and other friends and family raised enough money to secure 155 acres of land off Danielsville Road. By forming a limited liability company — Orange Twin Conservation Community LLC — the group was able to secure a loan to purchase the land. While 55 acres were set aside for development, the other 100 acres of forest and trails were put under a conservation easement.

Why It’s Newsworthy: In Athens-Clarke County, where an affordable housing crisis is paired with limited access to fertile green spaces, collectively owned land gives people education and experience in sustainable living.

The shareholders have grown to 23, including Carter’s mother, brother and father, as well as others living in the Northeast and around Georgia.

“We still are paying off the loan, but we’re in the final stages of it,” Carter said.

When the LLC first purchased the land, they had a vision — an eco-community with plenty of housing, garden plots and means to live off the land. The development plan was analyzed and approved by the Athens-Clarke County mayor and commission. But Carter said it would cost money — hundreds of thousands of dollars on top of existing property taxes and what’s left to pay off the loan — and they would have to tear down some forest. The same forest they’ve been protecting for 20 years.

“Seeing how much development has happened in town, our forest seems a little more sacred and precious,” Carter said.

Questions on Preservation

There are 45 conservation easements listed for Athens-Clarke County, according to the National Conservation Easement Database. The majority of outdoor spaces — including the 100 acres within the Orange Twin community — are held by the Oconee River Land Trust.

A conservation easement is a legal agreement that limits or restricts the development of land. Essentially, easements protect areas of land in perpetuity, or for as long as the easement is upheld by the parties involved. The shareholders for Orange Twin’s land went into one of these easements with the Oconee River Land Trust when the land was first purchased in 2000.

Conservation easements are a “really popular tool” for land conservation, said Christian Turner, associate professor in the University of Georgia School of Law. Turner has experience studying property and natural resource law.

“It’s a servitude on property that allows someone else power over the landowner’s use of their land,” Turner said. “What it does is it gives a third party the kind of right to enforce the agreement, and the agreement in these conservation easements is that they will not do certain things on the land.”

While conservation easements typically lessen the value of the land they cover because urban development is no longer an option, they create protections for that land in perpetuity, assuming the owner of the easement keeps it for that long. Public ownership of land — such as parks supported by taxpayers and managed by the government — is also an effective way to achieve conservation, Turner said, but it can be difficult to reach agreements quickly that way.

At Orange Twin, Carter said the shareholders have largely been letting the hardwood forest “heal itself.” While there are walking trails, an amphitheater and other features like a swimming hole and a stage, the forest surrounding the house has been largely untouched.

While future development of a “sustainable” community remains uncertain, 100 acres of hardwood forest will remain protected from large-scale development even when the shareholders aren’t in the picture.

“I would say it’s not a model for large scale protection of lands that we need to protect, important resources to restore wilderness and to fight against climate change,” Turner said. “But it’s a great model for protecting special places that people care about, and that they can passively enjoy.”

Collectively-Owned Spaces

Next to the house, Carter manages a flock of chickens, three goats, three herding dogs and a beehive the size of a fax machine. There are fruit trees — pear, apple and fig — littering the property. A muscadine vineyard sits less than a mile away. Small garden plots produce just enough beans, tomatoes, kale, mustard greens, okra and corn for Carter and her family to enjoy.

Behind a plastic picnic table in the side yard is a 9-foot tall banana tree, a “testament to global warming,” in Carter’s opinion. Access for recreation like camping, hiking and yoga at Orange Twin is limited to the shareholders, friends and family.

“It serves kind of as a kitchen garden with shareholders coming in and taking a plot or a row, or adopting something,” Carter said about the farmable land. “People have used the land and continue to use it from time to time for personal venture projects.”

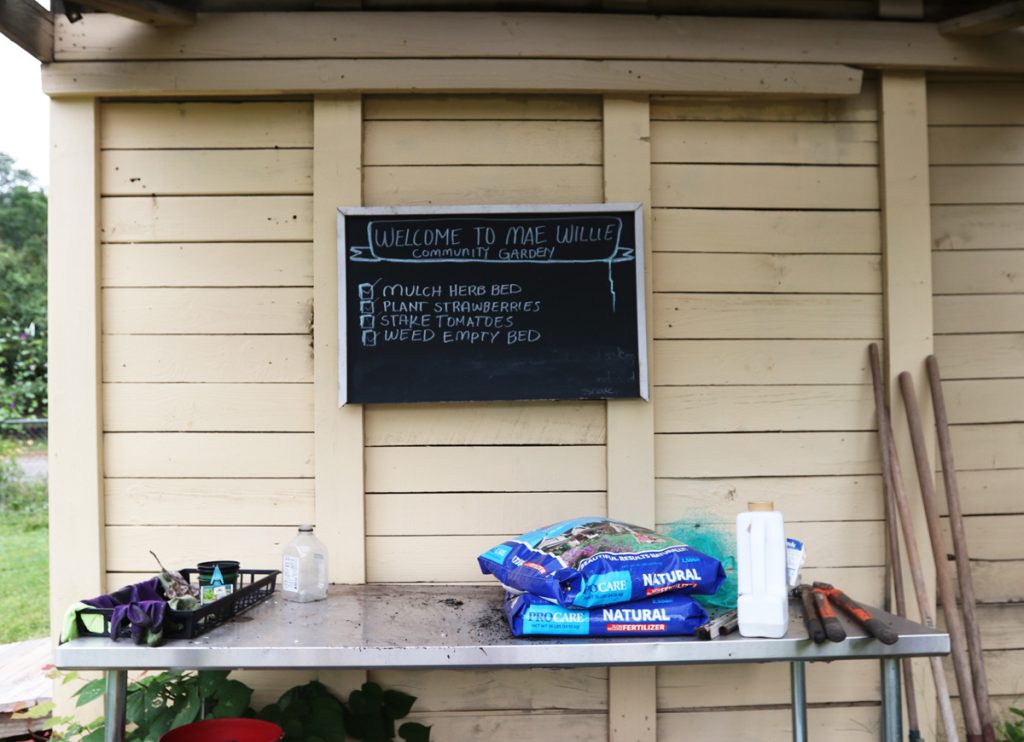

While Orange Twin’s land is protected in perpetuity, this idea of collective management can be tricky on properties with less security. Athens Land Trust Community Agriculture Coordinator, Cameron Teeter, spoke about her experience working with community gardens and shareholder-led management.

“One problem with community gardens is that they’re pretty vulnerable spaces,” Teeter said. “So people may allow us or allow a group to use a space, and then plans change for that property.”

The Athens Land Trust partners with more than 12 community gardens and holds conservation easements for 24 local properties.

“Ideally, what we do with our community garden network is that we have a strong group of people that come together and write the bylaws of how they’re going to use that space,” Teeter said.

In order to ensure the longevity of community-owned spaces, Turner recommends organizations and individual landowners consider how well shareholders can work together.

“It kind of depends on not only how reasonable the people are, but is their structure set up in a way to be resilient against kind of personality conflicts,” Turner said.

Back at Orange Twin, Carter and her mother, Nancy Carter, check on the chickens and set out water for the goats. The pair hope to see the original plan of an eco-community come to fruition someday, even if it just means having more people on the land, growing and learning.

Until then, the forest is protected.

“You can always turn a swamp into a parking lot,” Turner said about the value of protecting natural spaces. “The one thing we don’t know how to do is to turn a parking lot back into a working swamp.”

Sofia Gratas is a fifth-year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)