This was Ashley Dai’s experience, a first-year advertising and public relations graduate student at the University of Georgia from Shanghai, China.

Members of the Asian community across the United States have experienced increased racism since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, including a stabbing of an Asian-American family at a Sam’s Club in Texas.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Due to the origin of the novel coronavirus, which was first reported in Wuhan, China, on Dec. 31, 2019, there has been a rise in racist words and actions directed toward people of Asian descent.

Despite messages from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization against calling COVID-19 the Chinese virus or Wuhan flu, people and organizations continue to use the racialized term.

In a press conference on March 18, 2020, President Trump defended using the term “Chinese virus” and said, “It’s not racist at all.”

While he later condemned violence against the Asian-American community in a press conference and on Twitter, it hasn’t stopped distrust and racial scapegoating.

Finding a scapegoat is one of the most common responses to, among other emotions, anger and frustration, according to an article published in Psychology Today, and the current climate surrounding COVID-19 is no exception.

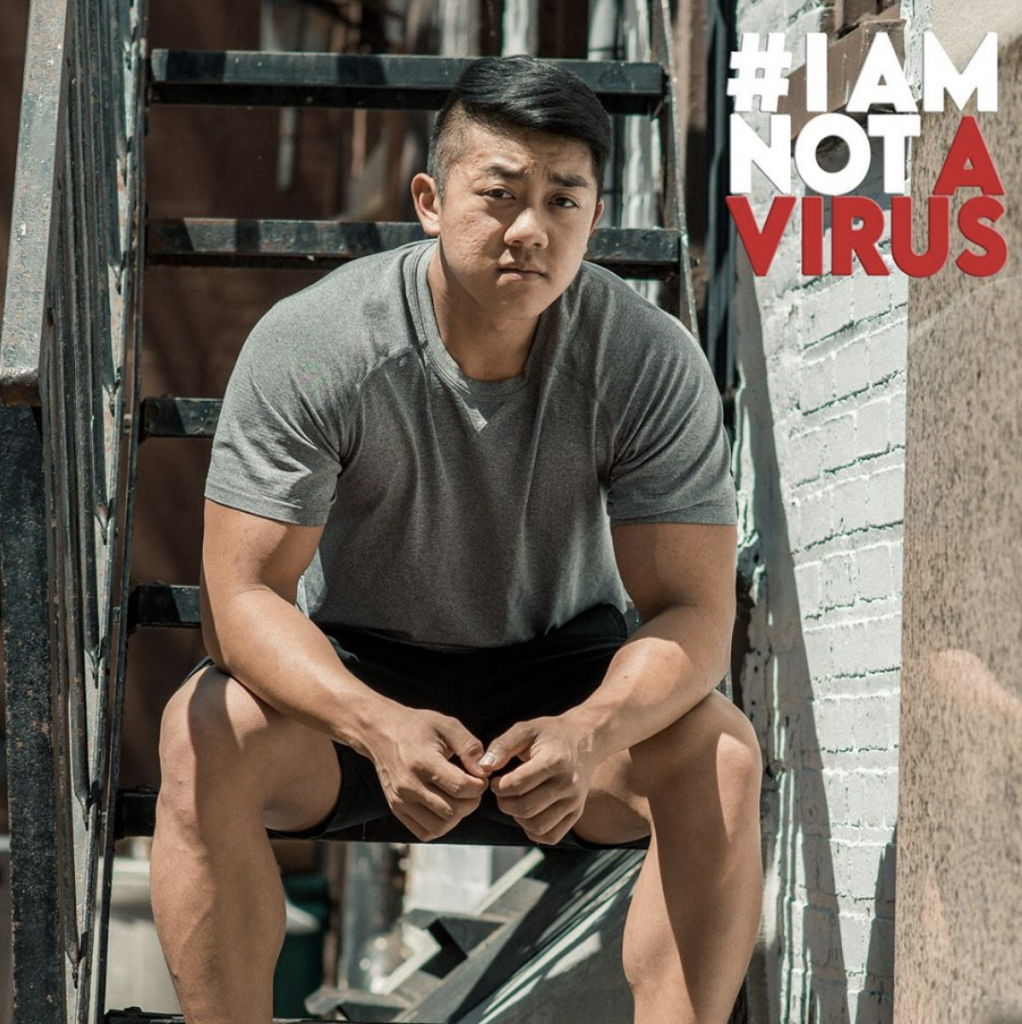

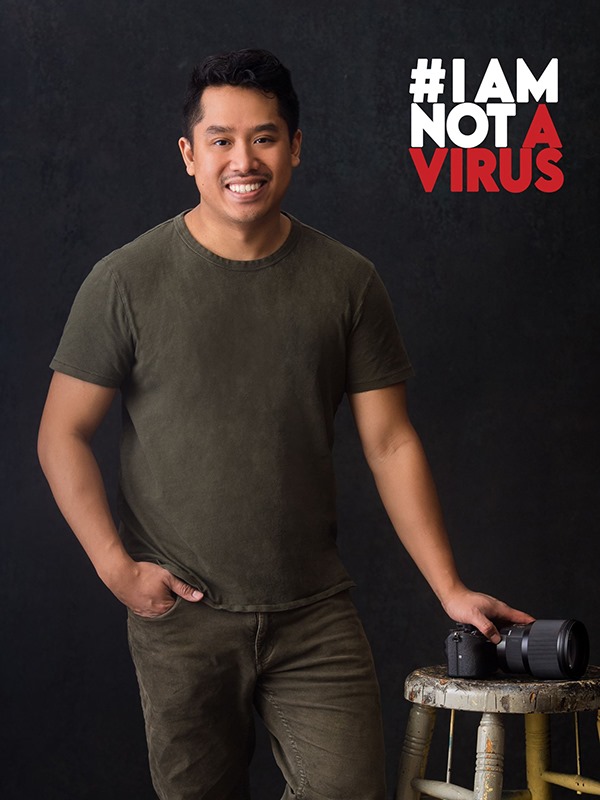

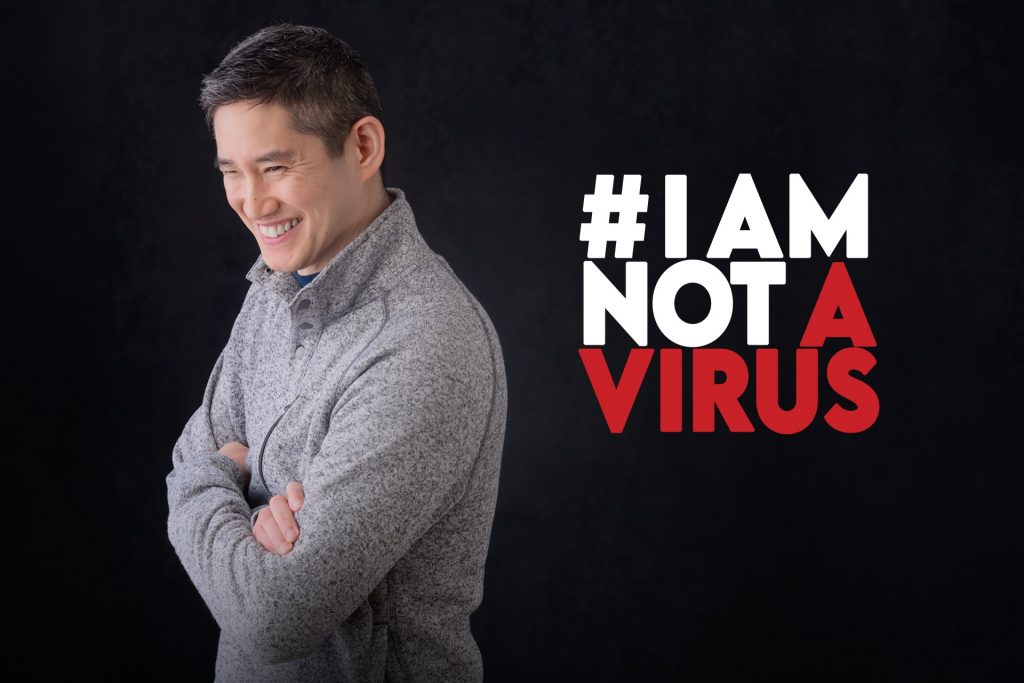

In response to a rise in xenophobic and racially-fueled actions, Connecticut-based photographers Moses Farrow and Mike Keo launched a social media campaign in March using the already popular hashtag #IAMNOTAVIRUS to increase visibility and encourage compassion for the Asian-American community.

Since then, Kelly Ha, a first-year graduate student at the University of Connecticut, has joined the campaign as its manager and has begun a mental health initiative.

“COVID-19 has affected my family socially and economically so I wanted to do something to make an impact. It greatly affects me seeing my family fear leaving the house because they worry that they will be attacked verbally and physically,” Ha said in an email. “All I want is for my family to feel safe.”

Farrow said the project began after reading a NPR article titled, “When Xenophobia Spreads Like a Virus.” One of the sources, a middle school student from Middletown, Connecticut, said other students in her class called her “corona” and asked if she ate dogs.

For Keo, pinning the virus to China is dangerous for the Asian community at large.

“This sets everyone on guard for anyone that looks Asian American … it’s highly dangerous,” Keo said. “It makes our community feel less safe and … I’ve heard from a few of our volunteers where they feel smaller when they’re by themselves.”

Since Dai was verbally assaulted while walking down the street, she hasn’t left her Athens apartment for fear of further abuse and even gets her groceries delivered instead of going out.

While Farrow, Keo and Ha didn’t share any personal experiences of racism or xenophobia, Keo said every experience is personal.

The campaign’s Instagram page features over 50 portraits of Asians and Asian Americans — from transracial adoptees to members of the LGBTQ community to those living abroad. At the project’s beginning, people came into the studio to get a portrait done. Now, members of the Asian community can submit photos, along with personal stories and three “I Am” statements.

The “I Am” statements, which come from Keo’s poetry background, seek to highlight who Asians are as individuals, as well as underscore the similarities that extend beyond any racial or perceived divide.

“It is a nice way for people to define who they are and the way they want to be defined,” Farrow said. “[It] gives them the power.”

Even before Farrow and Keo’s project, the hashtag was used by other members of the Asian community around the world to stand up for themselves and find a sense of solidarity and continues to do so.

Nurie Langlois, a sophomore Korean and Chinese major at UGA, is a member of the university’s Asian American Student Association and said the organization has used the hashtag on its Instagram story. She also spoke to the positive impact it has on the Asian community as a whole.

“It’s reminding people that we’re not the virus, we’re not the issue. We all have one common enemy, which is COVID-19, that we should be fighting,” Langlois said. “Don’t be fighting us.”

Finger Pointing

Even for those who continue to blame China for the virus, their threats and accusations often get hurled at other Americans of east Asian descent. Groups such as the Asian American Commission, based in Connecticut, and the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council have begun tracking violence against these groups.

Lehua Kono, who is of Japanese, Filippino, European and Pacific Islander descent, works in a pharmacy in Salt Lake City and said she’s had customers ask for another person to help them because of the way she looks.

Kono said it’s not uncommon for her to stand out in Utah, as the state’s Asian population is only 2.4%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. However, the sophomore international and Asian studies major at the University of Utah said she’s noticed people distancing themselves more from her since the beginning of COVID-19.

Kono also shared an experience her mom had when shopping at a grocery store where everyone in the aisle left when they saw her.

Back in Georgia, Langlois said she and her mother, who is Korean, were stared down by a caucasian woman while at a park before shelter-in-place orders went into effect. Langlois said the woman also coughed, without covering her mouth, and then walked away without saying anything.

“I don’t know if that was her being weird or her being subtle in some sense, but that was a very strange thing,” Langlois said. “My mom and I were definitely uncomfortable.”

For both Langlois and Kono, frustration stems from people blaming and scapegoating instead of fighting back against racism and supporting one another.

“It’s just unfortunate that an entire community … has to deal with this and be faced with the consequences,” Langlois said. “It became this kind of finger pointing of, ‘Who started this, who ruined my life,’ kind of deal.”

While the #IAMNOTAVIRUS hashtag is helping to spread awareness and combat racism, Langlois sees its online-only presence being a limitation since people choose who and what they want to follow on social media channels.

“I feel like it’s spread mostly within the Asian community … and also I feel like the people that are going to be spiteful in the first place normally aren’t the ones looking for that,” Langlois said.

On the other side, Keo said another challenge has been keeping up with the number of submissions and making sure everyone feels heard and supported.

And even though Farrow is no longer affiliated with the campaign, he said he will continue to advocate for the Asian American community — even after COVID-19 becomes a disease of the past.

“We’re definitely committed to … keep working as long as there’s anti-Asian rhetoric, as long as there’s Asian violence,” Farrow said. “It’s not like we can stop being Asian American and move on to the next thing.”

Rachel Priest is a senior majoring in journalism and history in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, respectively, at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)