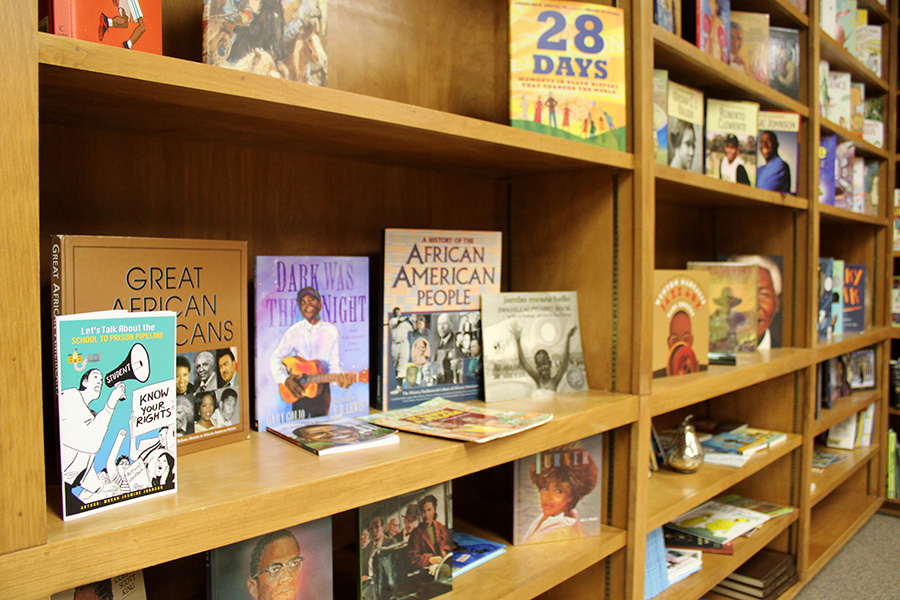

Books focusing on Black history and pride fill the shelves of a library. Along the walls, there are posters about historical Black figures, like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks, and there’s even a Juneteenth flag proudly hung in the center of a classroom.

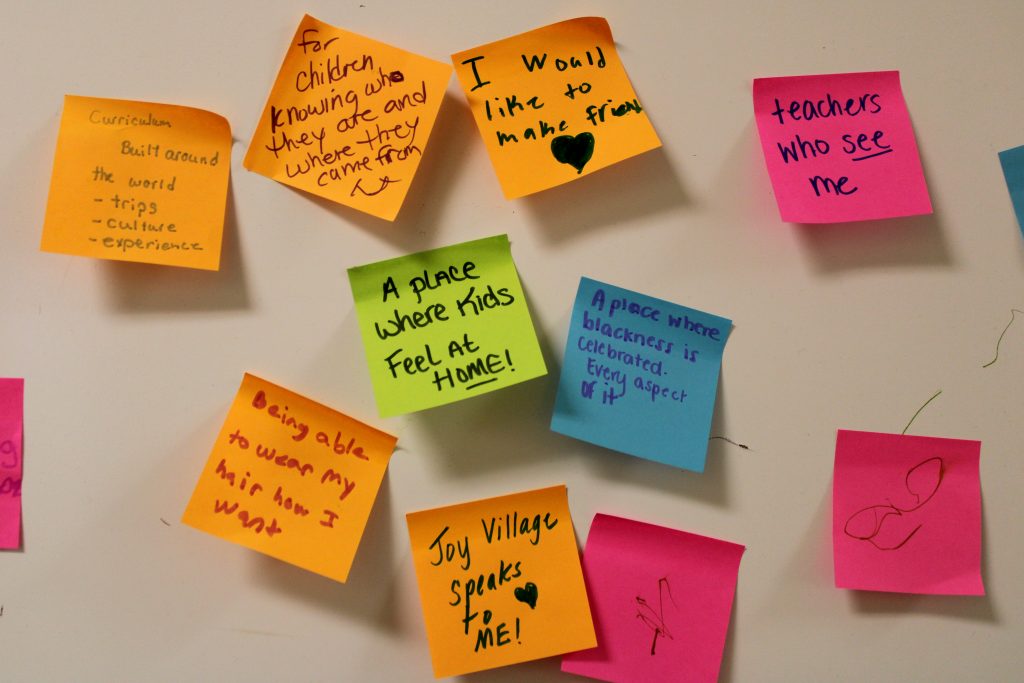

Walking around the Joy Village School, a K-8 private school opening in August 2022 that centers on the joy and thriving of Black youth, you can already see the work that goes into making the environment a place where Black students can learn and thrive. And although the school will focus on the thriving of Black youth, children of all races are welcome to attend.

According to Achievement Gap in CCSD, Clarke County School District’s student performance on the 2019 Georgia Milestones reflects that African American students from CCSD performed well below the state average and below their student group counterparts statewide.

Along with that, according to Student Discipline in Clarke County School District, an analysis of trends and disproportionalities in disciplinary infractions and consequences from 2014 to 2018, “African American students account for the majority of disciplinary infractions and that African American students comprise 50% of CCSD’s enrollment but 80% of students are referred for disciplinary infractions.”

CCSD declined to comment at this time.

When working in local private schools, Smothers observed that there’s a lot about Black culture in those spaces that aren’t allowed. For example, they were supposed to make sure the kids weren’t listening to rap music, or that they didn’t have their hoods on, and Smothers felt like these kids couldn’t be themselves.

Smothers says that there’s a lot of disenfranchisement of the Black community that is hard to overcome in our current school systems.

“My goal is that by pulling away we can kind of build up this little realm of positivity that can then serve as an example to some of the other schools of what’s possible,” says Smothers.

History of Race and Education in Athens

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and was unconstitutional.

“It shook the world. It shook the South in particular. And so there was an effort to resist falling through with the order,” says Fred Smith, the Director of the East Athens Development Center, who is Athens born-and-raised and oversees the Athens Black History Bowl.

In Athens in particular, Smith says, that in the 50s, multiple schools were constructed and for the first time the state put a significant amount of money into Black education, which happened throughout a lot of the south.

In September 1963, Smith says the Athens local school district offered freedom of choice, which meant that students could decide if they wanted to attend previously all-white schools, so a couple of Black students started attending those schools.

In 1970, integration fully came to Athens when the white school, Athens High School, and the Black school, Burney-Harris High School, combined to make Clarke Central High School.

Smothers emphasize she had learned in schools that integration was a great thing, but that was not always the case because there was a lot of grief involved since their schools were forcibly closed.

Smith says one result of integration was that Black students started to be tracked into lower-level classes, which is a trend that he saw into at least the 90s when he was working as the president of the local NAACP in Athens.

According to “Black Segregation Matters,” throughout the nation, desegregation was durable and peaked in 1988, but since then the share of intensely segregated minority schools, which are schools that enroll 90-100% non-white students, has gone up from 32.1% in 1988 to 40.1% in 2018, showing the trend of resegregation.

“Fast forward to the 80s and 90s. I mean some people would call integration a failed project, because, at that time, a lot of the white families started to move elsewhere, like to Oconee County. And then there was this resegregation of our schools, which we see in full effect now,” says Smothers.

Black students are far more segregated from white students now than in the Civil Rights Era, according to “Black Segregation Matters.”

According to the American University School of Education, this problem of resegregation is making predominantly Black schools continue to face economic, social, and structural challenges that predominantly white schools do not.

Today, both Smith and Smothers agree that the education system is not operating as it should.

Beginnings of Joy Village School

In June 2021, Smothers started doing pop-up schools at different sites of historical significance to the Black community in Athens.

Smothers said she decided on pop-up schools because she had been reading about the history of Black education and found out that during the Reconstruction Era, women would do pop-up schools anywhere, like in the woods.

One pop-up school she did was at the Varsity where Smothers said she would read books, play games, tour the location, and have elders from the community come and talk about what it was like organizing the citizens to integrate the Varsity.

“It was really designed to be this interactive learning experience where both the kids and their parents were getting a taste of my philosophy of education,” said Smothers.

It then progressed into having some camps in fall 2021, said Smothers, and instead of it being just a Saturday morning pop-up school, kids would come and spend one or two days to have a whole learning experience.

Smothers said she found the location of the school in October, which is on 320 Research Drive, and began pre-leasing the building in January. Not long after, they began the process of hiring teachers and enrolling students.

How the School Will Operate

“I’ve always had this dream about having a school that feels like school in the morning and summer camp in the afternoon,” says Smothers.

Smothers says that students will do their core subjects in the morning, but in the afternoon she wants to expose the students to as many different disciplines and activities as possible, like music, poetry, foreign language, or sport. With that, she also has put the word out to the community for people to come and share their skill sets with the kids during that time.

In the afternoon when the students go to their lab, they will go in multi-age groups called houses.

“They’ll actually be split into houses, ala Harry Potter, to do their elective activities. But our houses are going to be named for some of the last black neighborhoods here in Athens, like Lennintown,” says Smothers.

Smothers is very excited about this cultural piece of the school because she wants the students to feel a personal connection to centers of local history that they can carry with them.

The main subjects that students will focus on will be language arts, math, and Black history, but Smothers says her goal is for the students to be learning in an interdisciplinary way.

Smothers says that funding for the school has come from donors, corporate sponsorships, grants, and fundraisers.

According to the Joy Village School Handbook, tuition for the school varies based on family income level and payment plan options.

The Future

Smothers says that the response to the school has been very encouraging and that all the people she has talked to have been very supportive.

Currently, there are 40 students on the waiting list, but Smothers’s goal is to have 100 students. Smothers does not think that goal will be hard to reach, especially since the school is partnering with the Apogee Scholarship Fund, to help make the school more accessible to all families.

Joy Village School is also currently in the process of being accredited by the Georgia Accrediting Commission.

Smothers plans to expand the campus. She wants to eventually own the property the school is currently on and acquire some more so that the school can keep growing.

Ultimately, Smothers wants the school to be a sustainable institution, but she also wants families to have a sense of relief that their kids have a place where they can thrive.

“I think our school is going to just have a buzz in the air. I think it’s going to be filled with movement and laughter and dancing and art. I’m kind of just envisioning Miss Frizzle’s classroom but Black,” says Smothers.

Erin Johnson is a senior majoring in journalism with a minor in fashion merchandising and a certificate in new media studies.

Show Comments (1)

Thebalitravels

Great plan for education. Thank you