The jaws of the machine tear and pull at the stubborn ground like a mechanical madman. Dirt clods fall from the teeth of the machine as gravediggers force the ground to make way for another body — another COVID-19 body.

This is what the gravediggers at Master Grave Service, Inc., a grave opening and closing service in Bogart, do day in and day out. They have 19 to 20 staff members who dig graves for 35 to 50 funeral homes, spread as far away as the Georgia mountains to Augusta and into Atlanta.

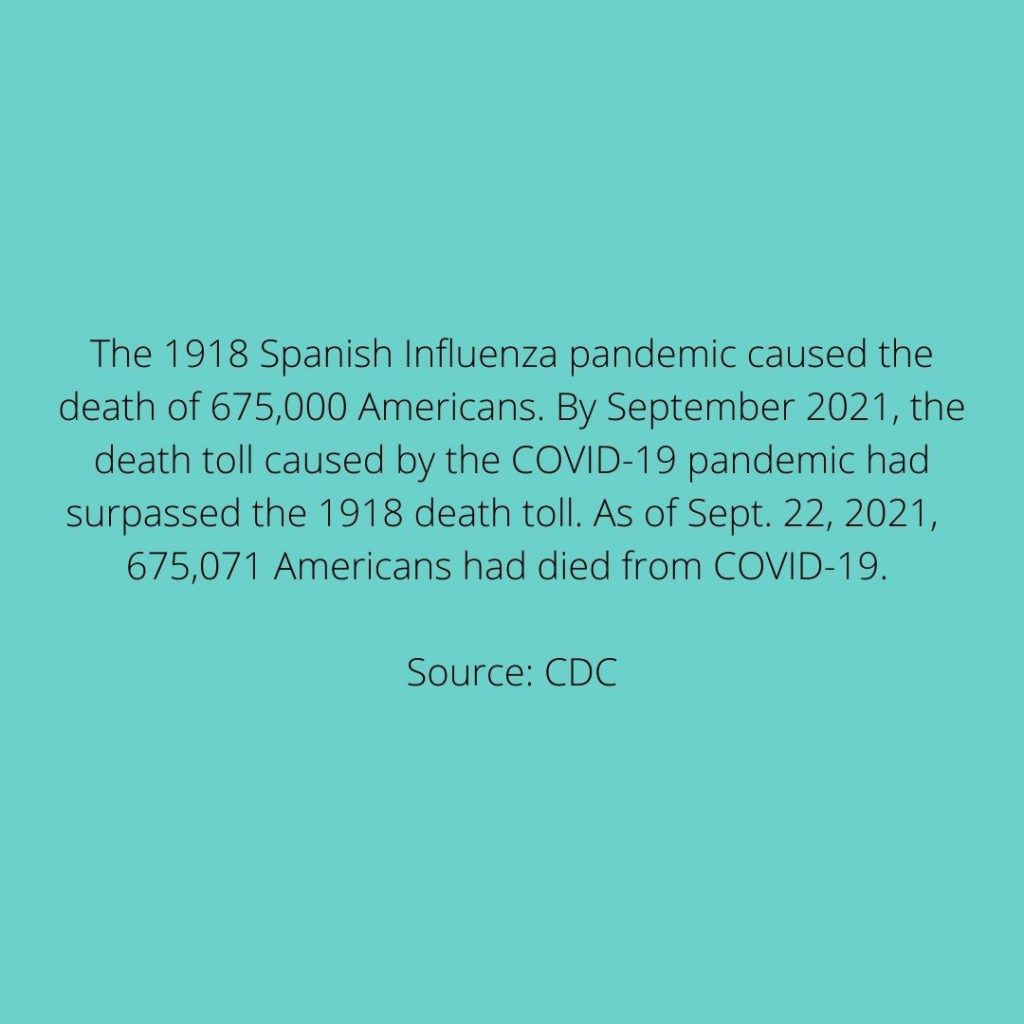

Why It’s Newsworthy: As of Oct. 1, 2021, COVID-19 has taken the lives of over 694,000 Americans, and it’s been up to the funeral industry to deal with those deaths. Their stories show how the pandemic has impacted yet another group of workers who often get overlooked.

In laying people to rest, gravediggers provide a last act of kindness to strangers. They perform a necessary role in society, but they often get overlooked.

“[People] don’t see the hours we put in. They don’t see the service we provide. They don’t see what we take home to our families because we give all that we can to these families that are in need,” Robby Smith, sales director at Master Grave Service, Inc. said.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Master Grave Service worked overtime to help families in need, but it came with a cost.

An Increase in Death

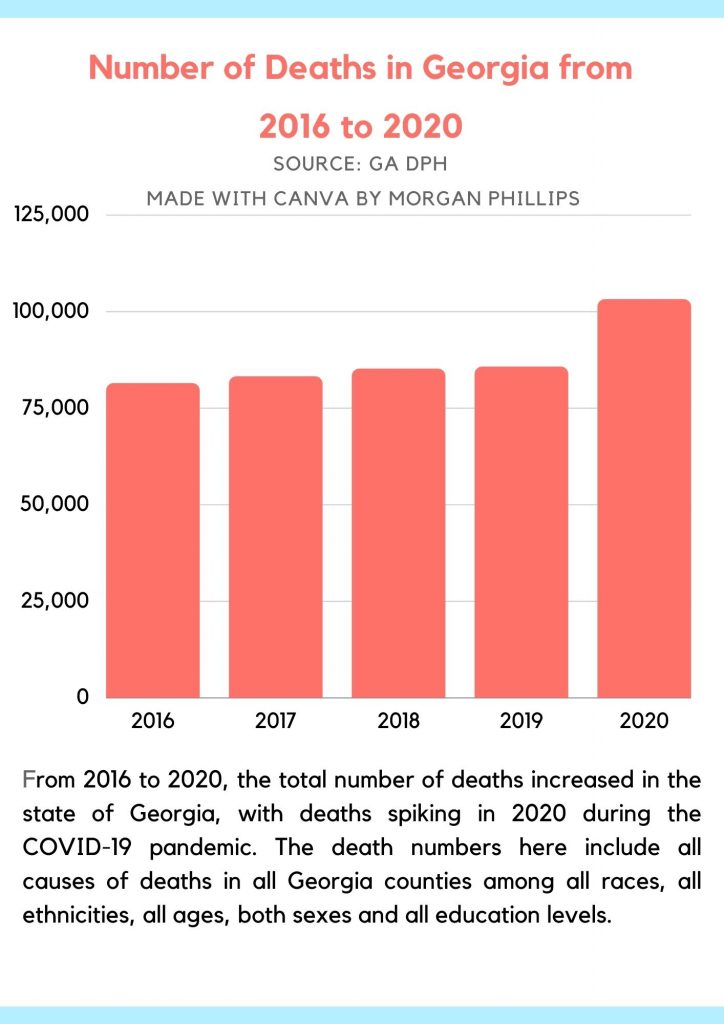

Typically, the funeral industry plans for a predictable amount of bodies they have to handle each year, but the increase in deaths caused by COVID-19 has overwhelmed and strained them. It’s been no different for Master Grave Service.

“We’ve seen a huge increase in the amount of deaths, just in this short amount of time … We’ve never seen this before. I’ve never even seen it in my 25 years,” Smith said.

Smith doesn’t know the exact number of bodies, but he knows that his staff has had to bury more COVID-19 bodies and that they’ve been busier since the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, their gravediggers were running three diggers between eight to 10 hours a day to keep up, and even now, they are still overwhelmed with bodies.

“It’s making everyone work seven days a week — that’s where we’re seeing most of the impact. [We are] having to tell funeral homes you have to call us to see if we can handle [another funeral] service that day — if we can take any more,” Smith said.

This level of strain for gravediggers hasn’t happened since 1918.

Gravediggers and Past Pandemics in the U.S.

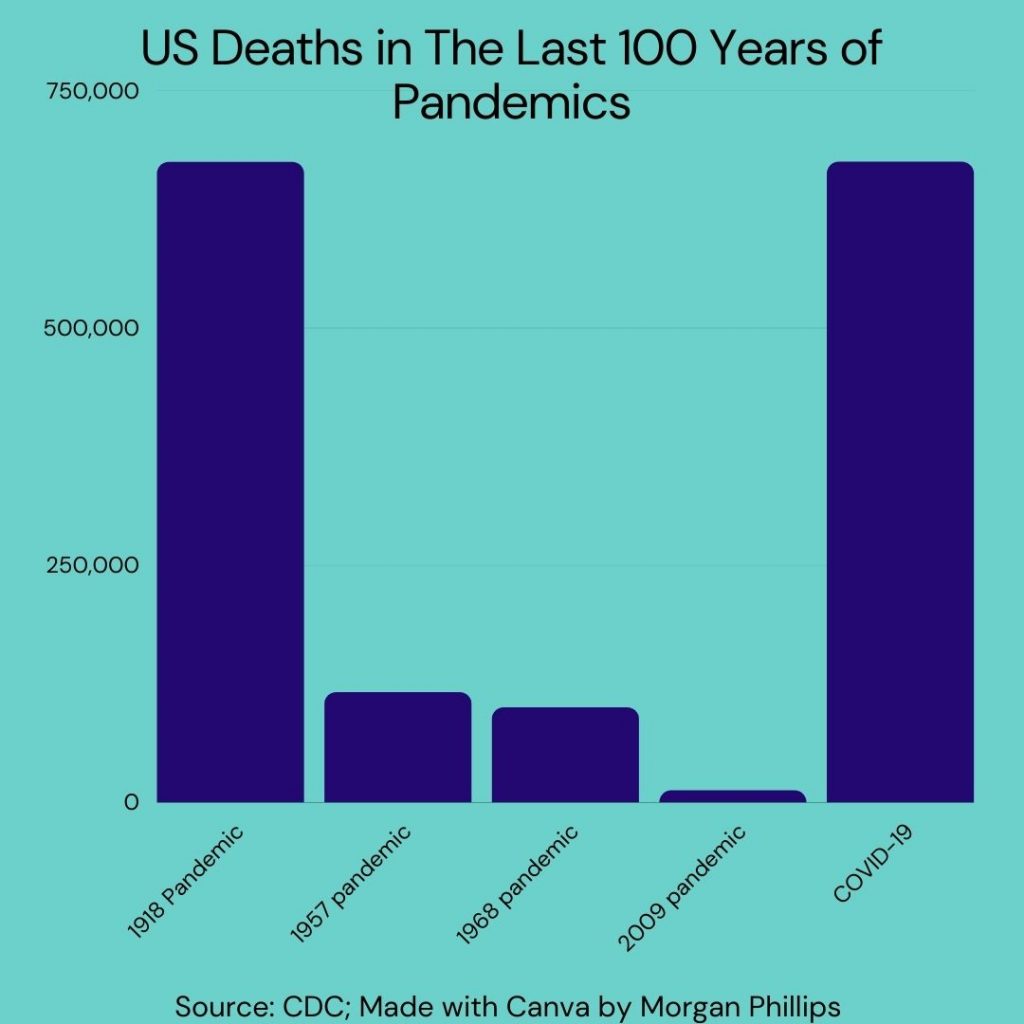

In the last 100 or so years, there have been four pandemics in the United States, according to the CDC — the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, the 1957 pandemic, the 1968 pandemic and the 2009 pandemic.

Of those pandemics, only the 1918 pandemic overwhelmed gravediggers because it claimed the lives of 675,000 Americans. The sheer number of bodies overwhelmed undertakers, gravediggers and casket makers. Across U.S. cities, bodies crowded morgues, were dumped in mass graves or were stored until burial.

There has been a similar level of strain seen among Georgia’s funeral industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. As of Sept. 23, COVID-19 had taken the lives of 25,338 Georgians, according to USA FACTS, and that number was in addition to the number of deaths occurring in Georgia each year.

Dealing with that increase in bodies took its toll on the gravediggers at Master Grave Service.

From the Mouth of a Gravedigger

Terry Thurmond is a gravedigger and vault technician who has worked at Master Grave Service since 1985. These days, he gets to work extremely early, receives his orders for the graves that have to be opened that day, climbs into his work truck and heads out to the first cemetery of the day. His truck is loaded down with a mechanical digger, wheelbarrow, funeral tents and shovels.

When the pandemic first hit, Thurmond was overwhelmed with a sense of urgency as more and more burials came through.

“I [just] wanted to make sure that we had our part taken care of for the family [because] the families were having a difficult time,” Thurmond said.

Eventually, the pandemic impacted Thurmond as well. He worried about his ability to do his job without getting sick, and he struggled with staying motivated to dig graves.

“Lots of deaths were occurring, and I [just] had to keep moving,” Thurmond said. “I just went to work harder.”

But the exhaustion kicked in nevertheless.

After a long day of digging graves, “[I was] exhausted, physically and mentally,” Thurmond said. “There were more deaths than we had experienced in many years.”

Thurmond and the other gravediggers at Master Grave Service have to be prepared to dig a grave in 24 hours time or less.

With the number of bodies, “that was difficult at times,” Thurmond said. “People [just] expected it to be handled [but] had no clue how much we worked.”

From the Mouths of Staff and Customers

The supervisors at Master Grave Service saw firsthand how the pandemic affected their staff.

Smith recalled nights during the pandemic when his staff had to stay after dark and finish filling a grave by hand, when normally they would quit at nightfall.

“There were times we’ve had to turn the headlights on on the truck to finish up the gravesite, which is dangerous. You can fall in a hole, hurt a leg or an ankle or a knee, but we’ve had to do it,” Smith said.

Some of Smith’s gravediggers reached a breaking point during the pandemic, and after hitting that point, they didn’t come back to work. Smith said they had lost between 10 to 12 gravediggers since the start of the pandemic.

“We have a lot [of gravediggers] quit. We have a lot of no-shows. We can see the exhaustion level on their faces and the stress,” Smith said. “They couldn’t take it … People [were saying,] ‘I just can’t do this anymore’. They were so emotional. They were so overworked. There was just so much for them to do.”

For the gravediggers who stayed, the emotions intensified.

“[They were] distraught, trying to do the best they could for those families [even] in the amount of deaths we were seeing … especially when it was about midway through [the pandemic], it was really just exhaustion and these raw emotions [were] coming through on these guys and for all of us. You were losing family and friends, and it was heartbreaking,” Smith said.

Funeral homes that Master Grave Service served during the pandemic also saw the toll on gravediggers.

Stan Evans, funeral director at Evans Funeral Home in Jefferson, Georgia, who contracted out his gravediggers from Master Grave Service said the gravediggers stayed in high gear to keep up with the bodies.

“People didn’t quit dying. When there were more of them dying, it really became a challenge to physically and mentally get through it all,” Evans said. “You really had to get into high gear to keep up with all this going on. It was a lot of work, but it was also a lot of mental stress trying to keep up with everything.”

The Strain Continues

It’s been a year and a half of dealing with more bodies than usual for the gravediggers at Master Grave Service, but Smith said that strain isn’t letting up.

August is typically their slowest month, but this year, it’s been one of their busiest months so far.

“We’ve never seen this. Summertime is always a little slower but not this year,” Smith said.

Yet, Smith said his guys are a breed apart.

“They’re in go-mode when they hit the door. They’re ready to get their orders, get in their truck and go do what has to be done,” Smith said.

As Thurmond said, “Truthfully, it’s just what we do.”

Morgan Phillips is a senior majoring in anthropology and journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (2)