Linnentown descendants gather at Ebenezer Baptist Church West in Athens on June 23, 2024. Many of the Linnentown descendants are involved in activism and want redress for an urban renewal program that destroyed Linnentown, according to activist and Linnentown descendants Hattie Thomas Whitehead and Christine Davis Johnson. (Photo Courtesy/Christine Davis Johnson)

Sixty years later, Christine Davis Johnson still remembers how the city would send tractors at 1 a.m. to push dirt into walls encircling her house in Linnentown. A historically Black Athens neighborhood, Linnentown was destroyed by urban renewal in the 1960s to make way for University of Georgia dormitories.

“The people came up and told the people in Linnentown they had to move and take the money or … they could take the land,” Davis Johnson said. “They would take the dirt and, 1 o’clock at night, they just pushed it, but they wouldn’t hit the house. They would push it.”

According to Hattie Thomas Whitehead, former Linnentown resident, author, activist and co-chair of the Linnentown Justice and Memory Committee, UGA has not taken full accountability for contracting with Athens to buy Linnentown without the residents’ approval or knowledge. She and other descendants want an apology.

“What I would like for them is to come to the table with the justice and memory team that the mayor assembled and work with us,” Thomas Whitehead said.

An apology would be the first and foremost.”

The Land of Linnentown Today: High Rises and Profit

Today, high rise dormitories on that property generate a value of $71.63 million for the university, according to qPublic records. It was once where Black families built community in segregated Athens.

When reached for comment, UGA media spokesperson Greg Trevor pointed to the acquisition as being a “lawful purchase.” He added that interviews with Linnentown descendants are recorded and stored in the Athens Oral History Project, maintained by UGA Libraries, as well as other aspects of Linnentown history that have been preserved in the UGA library system. According to Trevor, Linnentown descendants have been invited to add their interviews to the project.

“The Board of Regents lawfully purchased this tract of land from the City of Athens after an eminent domain proceeding,” Trevor said in an email. “Under Georgia law then and now, only the Board of Regents may acquire and own property on behalf of member institutions of the University System of Georgia.”

Descendants of Linnentown

Born in 1943 in Savannah, Georgia, Davis Johnson was raised in Linnentown. She lived there with her mother after her father passed away until 1965, when the city and university forced them out of their home. For years, she didn’t know she and other former residents of Linnentown were eligible for redress until UGA researchers Joseph Carter and Rachelle Berry reached out to them.

In the 1960s, the local Athens government used a federal program called urban renewal to force all Linnentown residents to sell their homes for less than they were worth. A report estimated that the loss of property cost the families a little more than $5 million. Davis Johnson and her mother were the last to leave in their part of the neighborhood, on a hill that a parking lot now spreads over. Her mother did not want to sell their house, but they were forced to accept a low price, according to Davis Johnson.

Urban renewal was a system that took place from the 1940s-1970s when the federal government used legislation to give funds to cities like Athens to use eminent domain to take land and use it for public redevelopment projects. The University of Richmond’s “Renewing Inequality” project found that 298 families in Athens were displaced by urban renewal projects between 1950-1966, the majority of them families of color.

“Sometimes you don’t have a choice,” Davis Johnson said.

My mom was not going to fight, but she wasn’t going to be pushed out until they started pushing that dirt.”

According to Thomas Whitehead, she and her family were also forced to move, and she has since spearheaded the movement to claim redress and recognition for Linnentown. Those efforts include her activism, the publication of her memoir “Giving Voice to Linnentown” and the creation of a musical, “Linnentown: The Musical,” which was performed at the Classic Center in spring 2024.

“We moved to public housing on Rock Spring homes, because at the time we moved, it was segregation, so we couldn’t move to anywhere, we had to move to Black neighborhoods,” Thomas Whitehead said. “It was just stressful, and trying to find affordable housing in Athens, which was not affordable then and not affordable now either.”

Because of the Linnentown Project’s efforts, the ACC Mayor & Commission approved a resolution in 2021 recognizing the harm caused to Linnentown residents by Athens and UGA. This led to ACC pledging $2.5 million to create more affordable housing for lower income Athenians and to create the Athens Center for Racial Justice and Black Futures, which is slated to begin construction of a physical location at the Classic Center in 2025. The other $2.5 million was supposed to come from UGA, but the university has so far refused to acknowledge its role in evicting the Linnentown families.

While descendants have physically moved on, the memories remain. In the meantime, Davis Johnson wants UGA students to remember Linnentown.

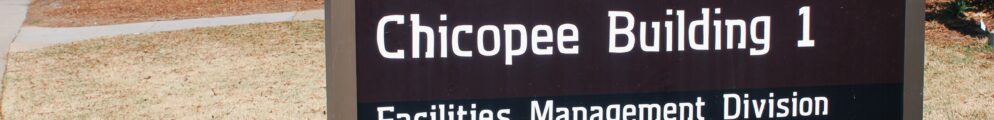

“Just to know that there was a thriving Black neighborhood, and to just see some of us, where we are, what we’re doing,” Davis Johnson said. “That would be great, just for them to know. And when they see the sign down there and see Linnentown Lane and understand why it was changed.”

ACC is still involved in efforts to preserve the memory of Linnentown. Currently, they are working on getting an art piece and signage on Linnentown Lane, but Thomas Whitehead hopes that there will be no obstacles from UGA.

“I’m hoping that UGA plays a role in helping this come to pass,” Thomas Whitehead said. “I hope there’s no obstacles thrown up to prevent it from occurring.”

Katie Guenthner is a junior majoring in journalism, Spanish and Latin American and Caribbean studies.

Show Comments (1)

albert

Please show the general location of this project and the land taken– map or diagrm with street names – thanks sj