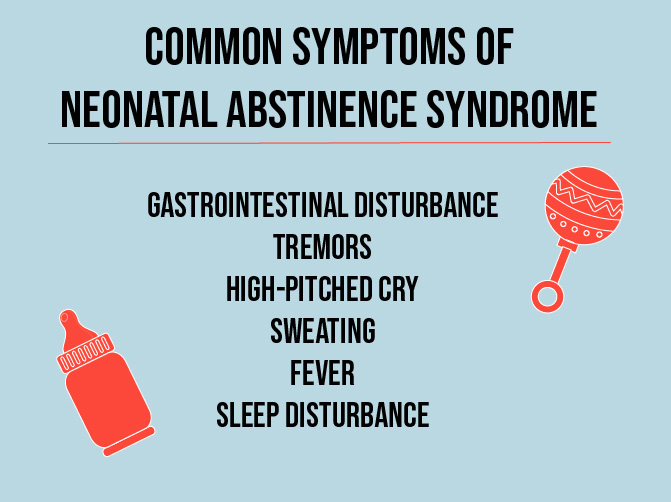

Georgia’s number of confirmed cases of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, a withdrawal condition babies may experience due to prenatal exposure to opioids, almost doubled from 2016 to 2017, according to a statewide Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome summary conducted by the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Pregnant women face many barriers to receive treatment for substance use disorder. Despite Georgia’s opioid awareness initiatives, there’s still a long way to go in terms of pregnant women receiving adequate health care.

Karen Kuehn Howell, assistant professor at Emory University School of Medicine, examines high-risk maternal behaviors and developmental issues. Yet after 30 years of research, Howell still notes the complexity of the situation.

The lifestyle of a pregnant woman with substance use disorder can be fairly chaotic, including irregular doctor visits, inadequate nutrition and lack of prenatal care which are huge developmental risks for a baby, according to Howell.

Treatment Options

Medication-assisted treatment, specifically involving the drug methadone, is the standard of care for treating opioid addiction, according to a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Nobody feels great about giving an addictive drug to a pregnant woman, but methadone during pregnancy has been found to level off use of other drugs and reduce the chance of overdose,” says Howell.

But if the mother uses methadone, the fetus still might have withdrawal issues. The average hospital treatment for a baby with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome is 16 days, according to Howell.

The irony here is that you treat the baby’s opioid withdrawal with another opioid,” says Howell. “Hopefully, by the time the baby does leave the hospital, it’s free from any kind of pharmacologic intervention and could probably be cared for just like any newborn.”

Amanda Abraham, assistant professor of public administration and policy at the University of Georgia, stresses that extensive research and clinical work makes medication-assisted treatment a valid option.

“If it’s against their beliefs or they feel like it will be stigmatizing or it won’t help them, they don’t have to take it,” says Abraham. “[Medication-assisted treatment] is the gold standard in care and there’s the most scientific evidence around using medications with behavioral therapy.”

In Athens-Clarke County, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities funds Advantage Behavioral Health Systems, which offers residential treatment specifically for pregnant women or mothers who have children with a substance related disorder.

Advantage Behavior Health Systems allow the child to live on-site with the mother as long as the child is under the age of 12 and in custody of the mother.

Access and Availability

After 13 years of looking into the barriers to medications, Abraham found that insurance and cost are some of the biggest obstacles for those seeking treatment for opioid addiction.

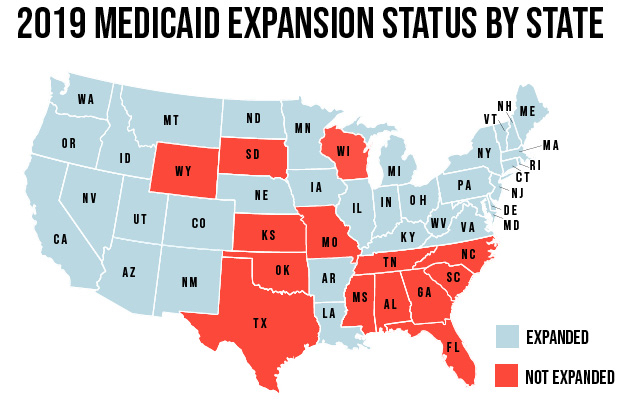

One way that Abraham recommends breaking down these barriers? Medicaid expansion.

“Under Medicaid expansion, those plans are required to cover treatment for substance use disorder,” says Abraham. “It’s the first time that any insurance plans have ever been required to cover it in history…Georgia did not expand.”

Without Medicaid expansion, the state has the burden for providing treatment for people who aren’t insured, according to Abraham. This means that patients are limited to the treatments and services available from the state.

But what would Medicaid expansion cost Georgia? Abraham suggests that the shift of people from uninsured to Medicaid would actually leave the state with more money.

“All of the money that the state is using to pay for the uninsured could be used to address the top needs,” says Abraham. “The state could recoup some of the money on the treatment services for people who are uninsured because those people are shifted to Medicaid.”

Fear and Stigma

In addition to tangible barriers, pregnant women also face unique psychological factors when pursuing treatment for substance use disorder, according to a report on opioid use in women by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health.

Andrea L. Dennis, law professor at UGA, finds that fear of incarceration and custody loss creates a difficult cycle for pregnant women who want to get help with addiction, but are apprehensive about the possible consequences.

One way that Athens-Clarke County addresses this cycle is through family treatment courts for parents with substance use disorder. During the 12-18 month program, participants will follow a treatment plan to help expedite recovery and family reunification.

However, Dennis recognizes that, in some cases, health care within the criminal justice system may be the most optimal alternative for a mother with substance use disorder.

I would say that the access or level of prenatal care in a corrections facility is not that high, but maybe the argument is that it’s better than what would be received or not on the streets,” says Dennis. “At least some care is better than no care, if no care would’ve been the other standard.”

The Office on Women’s Health’s report also states that social stigma around mothers dealing with addiction could be a factor for women seeking treatment.

Women with caregiving responsibilities may find going to treatment and receiving treatment more of an issue, suggests Howell, because the mother must find and pay for child care.

How does Georgia tackle the stigma and shame that mothers face when pursuing treatment? Howell proposes public awareness and education.

“I think the only “good” thing that comes from the whole opioid crisis is that it has raised a level of awareness about substance use disorder and addiction in general,” says Howell. “I hear so much more talk about treatment than I ever have before. I’m very optimistic.”

Mallory Thomas is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.