On a cloudy Saturday morning, Stacia Knowles sits criss-cross in her seat on the patio of Jittery Joe’s, a thermos of tea positioned in front of her. If not for the navy blue scrubs, Knowles’ calm appearance and articulate speech give off the impression of someone who just woke up after a restful night of sleep. In reality, however, Knowles has just finished a 12-hour shift at St. Mary’s Hospital in the Neuroscience Critical Care Unit (NCCU) where she regularly treats “the sickest of the sick” and spends most of the shift on her feet.

Several studies, including a 2019 study by Amber Adams, et al., identify nursing as a profession that leads to burnout without treatments for burnout ever entering the conversation. The study found that implementing a “toolkit” of resources for emergency department nurses, including added support, reduced nurse turnover and burnout. Additionally, a 2017 study by Reihaneh Babanataj, et al to determine the effects of resilience training in ICU nurses states that ICU nursing exposes nurses to more stress than other types of nursing, which can lead to “occupational stress” or burnout.

Although she has always worked in high-stress environments like the NCCU, Knowles, 39, is an example of a caretaker who manages her stress through communication and habits formed in nursing school; as a result, she has avoided the burnout that plagues others in the profession. Having experienced burnout in her previous job working in animal control, Knowles stepped into her new career with strategies to prevent it from recurring.

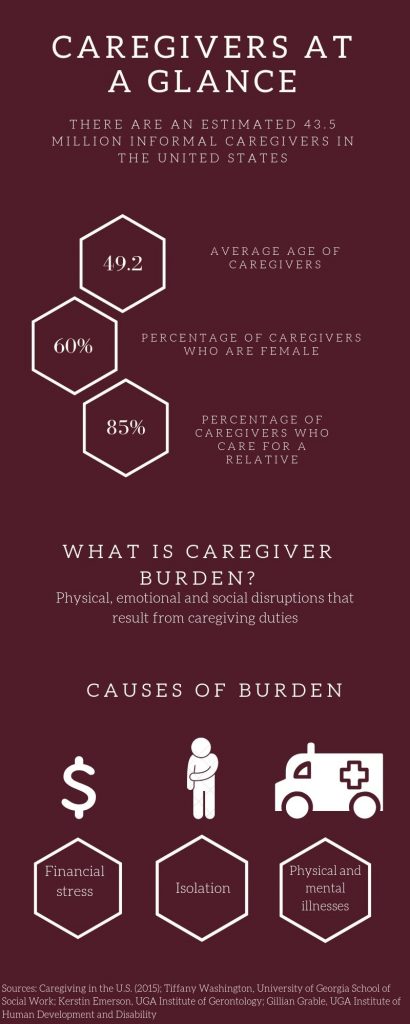

Caregiver Demographics

Caregivers can be divided into two categories: formal and informal. 43.5 million caregivers are cited in a 2015 study called “Caregiving in the U.S.,” and they are classified as informal, meaning they are family members, friends, neighbors or community members who go unpaid for their work.

“Caregiving in the U.S.” identifies that caregivers come in all ages and ethnic groups.

With this diversity in the United States in mind, 60% of caregivers are female and the average age of caregivers is 49.2 years, according to “Caregiving in the U.S.” Additionally, Hispanics had the highest estimated prevalence in the study, reporting 21% in the survey.

Conversely, the average age of a care recipient is 69.4 years, and 65% of those surveyed in the “Caregiving in the U.S.” study are female.

With all the concrete details of the profession in mind, a less tangible factor among caregivers is a desire to help people.

Knowles is a caretaker professionally through her nursing job, but was once one of the millions of informal caregivers in the United States. For her, caretaking is something that transcends her work life, and she feels like she cannot “turn off” her compassion.

“You don’t do this to get rich,” Knowles says. “You can be comfortable, but you do it because it’s like this need to fix things and it’s a need to help people.”

Loneliness and Caregiver Burden

In the 2017 book, “Something’s Got to Give: Balancing Work, Childcare, and Eldercare,” authors Duxbury and Higgins reference a definition of caregiver burden as “the physical, psychological or emotional, social, and financial problems that can be experienced by family members caring for older adults.” Caregiver burden results from duties of caregiving and can manifest itself in different ways. For caregivers, the duties and the people they work with can contribute to this burden, and the effects can be wide-ranging as well.

According to Kerstin Emerson, clinical assistant professor in the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Georgia, risk factors for loneliness among older people include major health changes, widowhood and moving. This loneliness has been linked to physical ailments such as high blood pressure, disability and increased risk of illnesses like the flu.

Gillian Grable, community support at the Institute on Human Development and Disability at UGA, works primarily with people with disabilities, but says that their experiences often overlap with the experiences of older people. According to Grable, two factors that cause the most stress for caregivers are poverty and feeling isolated. Along with these factors, a care recipient who is angry or lonely can also affect the stress levels of the caregiver.

Even more stressors are presented in “Something’s Got to Give.” According to Duxbury and Higgins, the top objective burdens of caregiving, reported through a survey of Canadian caregivers, are connected to not having adequate time and energy. Objective burdens are defined in the book as “observable disruptions or changes in various aspects of caregivers’ life and household that can be attributed to their caregiving responsibilities.”

Knowles attended nursing school for four years at Athens Technical College. Prior to and during her time at school, Knowles was in a long-term relationship with a man named Josh, who had schizotypal personality disorder that eventually evolved into schizophrenia. In their 12 years together, Knowles often acted as a caretaker for Josh, as he was often unable to keep a job. Knowles cared for him while simultaneously working full-time in animal control and going to nursing school.

“I think personal caretaking is 10 times more stressful than what I do for a living,” Knowles says.

In January 2017, Josh’s paranoia along with other health problems worsened, and he committed suicide. Knowles was the one to find him. It took her a year to recover from the situation, and she focused heavily on her last semester of school during this period and also began going to therapy.

For Knowles, part of being a caretaker is the feeling that you have to save everyone, including loved ones.

“You don’t realize the ones you love are different, they’re not your patients,” Knowles says.

Effects of Caregiver Burden

For caregivers, burden presents itself most evidently in physical effects. Issues referenced by Tiffany Washington, assistant professor in the School of Social Work at UGA are depression, social isolation, stress and physical health conditions.

“Some of what we’re finding is that caregivers often neglect their own health as a result of their caregiving role,” Washington said.

Knowles works with patients with brain injuries, which requires physical labor such as turning patients. According to Knowles, this activity can cause physical strain for nurses over time.

A lack of knowledge for this specific aspect of caregiver-care receiver relationships is demonstrated in a 2019 study in the Netherlands by Wendy Kemper-Koebrugge, et al. “Actions to Influence the Care Network of Home‐dwelling Elderly People: A Qualitative Study.” The study focused on people of people age 75 and older with a combination of formal and informal care networks, studying the actions of these networks and how they affected the care recipient. For both types of caregivers, researchers found that both types “did not really know how the elder person perceived the support provided by them.”

For both groups, loneliness can foster physical ailments and vice versa. The relationship between caregivers and care receivers can also exacerbate these issues depending on the caregiving scenario.

For Jayne Placey, 47, coordinator of residential services/CDS at Hill Street and Arioli Residential Care Homes in Barrie, Vermont, checking in on everyone involved is critical when a patient is approaching end of life. Placey has been coordinator for 12 years and prioritizes supporting her staff of nearly 50 people.

“Probably the most stressful time is when we do have somebody that’s passing away, because for me in my role, I not only want to be here to support the individual passing, but also their family if they do have family and also the staff,” Placey says.

Combating Caregiver Burden

While doing rotations in nursing school, Knowles fell in love with the NCCU, the unit for patients with brain injuries, and knew she wanted to work in that department. According to Knowles, the typical path for nurses after school is to work as a floor nurse to learn the basics and work with more stable patients, followed by moving into other departments like the ICU. Knowles, on the other hand, went straight to the NCCU after school.

As an NCCU nurse, Knowles has to wear many hats. According to Knowles, nurses in her department are told they have to think like doctors to do the work they do.

“You have to be a psychologist, you have to be a caretaker, a therapist, you have to do all of these things,” Knowles says.

ICU nursing may not be for everyone because of its intense and adrenaline-filled nature. This is the case for Allie Kerr, emergency room RN at St. Mary’s and friend of Knowles. The two met at nursing school and have been friends since, but work opposite schedules: Kerr works 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the emergency room, while Knowles works 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. in the NCCU.

I couldn’t do what she does,” Kerr said.

Part of the reason Knowles works well in the NCCU is her natural drive to work in high-stress environments, and the other reason is also related to stress: Knowles developed certain habits in nursing school to cope with stress.

One of her habits is taking walks around her property. At her old property, Knowles would take walks around the lake near her home with her dogs. Having recently moved to a new property with her fiance, Carden Price, Knowles has a farm of 27 acres where she walks her dogs and cleanses her mind of the previous night at work.

According to Knowles, older and more experienced nurses sometimes become jaded over time and struggle to empathize with patients, and they do this as a protective measure after years of interacting with patients who are sometimes violent and delirious.

“If I didn’t have my walks where I de-stress from the night and have that alone time, I would probably start getting the same way,” Knowles says.

Knowles also attributes stress relief to talking with both her therapist and Price. Price is also a nurse, and they met about two years ago working at the hospital. With their backgrounds in caretaking, Price is often able to detect when Knowles is stressed.

“As a caretaker, you try to hide [your stress] to an extent because you don’t want whoever you’re taking care of to see you getting stressed out, because it can stress them out,” Price says.

For Knowles, talking with Price, who is a more experienced nurse, helps her unpack the day. Together, they review different scenarios with patients including how they tried to “code” or resuscitate patients and treatments they used.

Through therapy, Knowles has been able to overcome some of the mental health struggles in the aftermath of her experiences with Josh. Speaking with her therapist, whether about personal issues or about work, is another way Knowles can handle the stress.

“It’s wonderful to talk to someone who’s a caretaker in another way,” Knowles says.

Like Knowles, Placey has some stress-relieving behaviors that she practices after work.

“I live on a dirt road up here in Vermont in a log cabin, and when I get off that main road and I hit my dirt road I try to leave everything I can from work at that dirt road,” Placey says.

Maintaining Momentum

Locally, nationally and internationally, methods are developing to reduce caregiver burden and the isolation it often produces.

According to a 2019 study in California by Lourdes R. Guerrero “Training for In-Home Supportive Services Caregivers in an Underserved Area,” undergoing training programs reduced the stress caretakers faced when caring for dementia patients.

For Grable, reducing caretaker stress is one of the priorities in her work, and she has worked with an approach called person-centered support. The goal of this approach is to help a vulnerable person remain in the community have a more fulfilled life. According to Grable, person-centered support comes in two phases. Phase one is a small gathering where the vulnerable person, such as an older person, brainstorms with their care network what they want to do each day and what they need help with; phase two is physically drawing and writing out the plan.

Part of the process is inviting other people into the network to help the person in these everyday tasks. According to Grable, vulnerable people are often hesitant to reach out for help with certain tasks even though people around them are willing to help.

“A lot of times it’s really hard for people to reach out because they’re afraid of being rejected, they’re afraid of hearing the ‘no,’ and yet a lot of times people are willing to help but nobody’s reached out and said ‘will you help me?’” Grable said.

Washington has research that involves designing interventions to support caregivers providing care for older adults or people with dementia. She is also building support for respite, or breaks for caregivers, in order to “give them an opportunity to step back temporarily so they have time for self-care.”

Placey and Knowles are two such caregivers who take time for self care.

Even though she manages her stress well, Knowles emphasizes that there is not one stress-relief method that works for everyone. However, having a support system, like what she has with Price as well as other nurses at the hospital and her therapist, is something she supports for all nurses.

Placey has worked in the field for 26 years. Part of why she has stayed in the profession is her passion for helping people.

“I think that everybody deserves a great quality of life,” Placey says.

Anika Chaturvedi is a senior at the University of Georgia majoring in journalism with a political science minor and new media certificate.

Show Comments (0)