Georgia’s women writers — from Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone with the Wind” to Flannery O’Connor’s haunting Southern Gothic tales — have played a key role in shaping and redefining the landscape of Southern literature.

At the Richard B. Russell Special Collections Library in Athens, the archives reveal the legacies of these women through handwritten notes, unpublished letters and manuscript drafts. Collectively, they weave a narrative of literary achievement, cultural struggle and enduring obstacles — particularly for women of color.

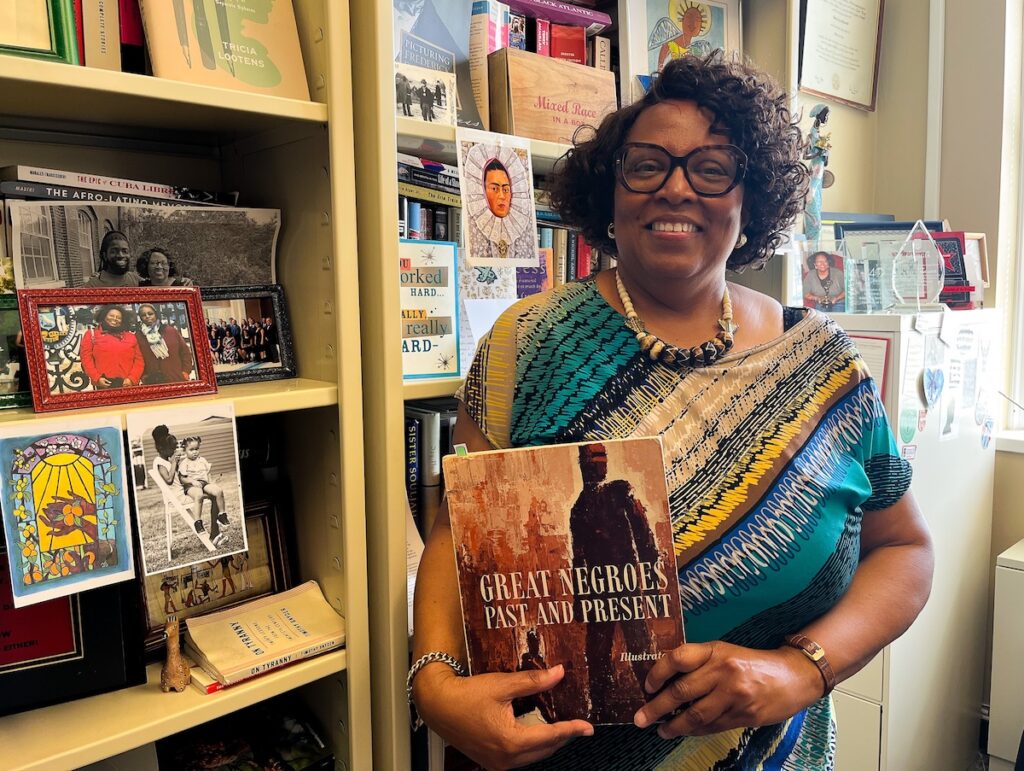

“Too often [we] have thought about Southern literature more superficially,” said Barbara McCaskill, Associate Academic Director for the Wilson Center for Humanities and Arts. “[We have] not been tuned in to the diversity of voices that come out of the South. Those voices are male and female. Those voices are Black, white, Latinx. There’s a diversity of voices that the mere label Southern woman writer confronts and often challenges.”

Why It’s Newsworthy: By spotlighting Georgia’s women writers and the archives that preserve their work, this story brings attention to the powerful literary voices that have shaped the state’s cultural history. It also underscores the importance of access, representation, and memory in how we understand Southern identity today.

Legacy & Controversy: Margaret Mitchell’s Old South

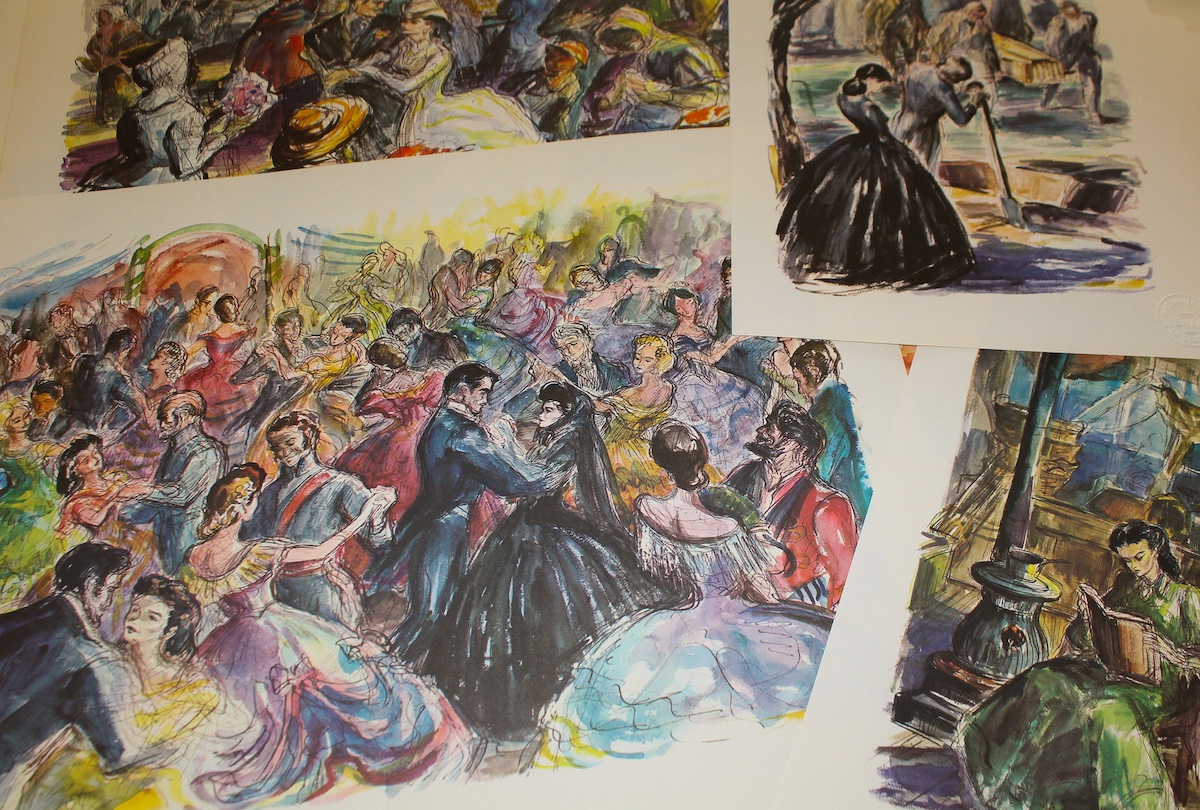

Margaret Mitchell remains one of Georgia’s most famous — and debated — literary figures. Her 1936 novel “Gone With the Wind” became a publishing sensation. The 1940 film sought to sanitize the novel’s racist elements, including references to the Ku Klux Klan and racial slurs. Yet, the novel remains tied to a nostalgic, if misleading, portrayal of the Old South.

Though Mitchell was never entirely comfortable with the cultural weight her novel carried, it became a symbol of Old South nostalgia.

An October 1940 letter from Mitchell details, “From the time when ‘Gone With the Wind’ was published, I have consistently refused to permit my name to be used in commercial promotions, and I have no intention of altering that policy.”

Despite this reluctance, the novel has been used in ways she likely never intended, including as a backdrop for Old South-themed events that glamorize slavery.

For women of color, literary recognition was harder to attain. McCaskill said they often relied on Black newspapers, academic institutions, and activist groups to build their own networks.

“The South faces, still today, perceptions from Americans who are non-Southerners that are negative,” McCaskill said. “That has influenced the reception that American readers and publishers might have toward Southern writers.”

Beyond the Belle: Enduring Power of Georgia’s Women Writers

Other prominent Georgia authors explored different approaches to storytelling.

Olive Ann Burns embraced the intricacies of Southern culture. Her novel “Cold Sassy Tree,” inspired by her upbringing in rural Georgia, offers a personal portrayal of small-town life. Burns’ background in journalism lent her writing a grounded, observational tone that resonated with readers.

Her husband often joked she was “born” into journalism; her father delivered her before the doctor arrived and laid her on a newspaper.

Anne Lewis followed a similar path. Through her tenure as editor of Georgia Magazine, Lewis provided a platform for emerging Southern writers. In her 1985 article series “I Was A ‘First’ In Buladen,” Lewis reflects on her time as a schoolteacher in Appalachian North Carolina, where an underfunded education system became starkly clear.

After her first week, Lewis found “some [students] who had trouble reading and knew no history or geography could figure like a computer.” This experience wasn’t just an observation. Lewis understood the power of storytelling as a medium to capture the essence of a region and its people.

Flannery O’Connor, perhaps one of Georgia’s most studied literary figures, gained national acclaim through her short stories, including “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” Known for her depictions of religion, morality and the grotesque, O’Connor remains a central figure in American literature.

Her legacy continues through the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, presented annually by The University of Georgia Press.

“We had almost 350 entries last year,” said Sarah Shermyen, a literary editor at The Press. “That has ended up kind of being a thing that helps authors start their careers.”

“The best-known Southern women writers … all kind of didn’t do the Southern Belle thing,” Shermyen added. “Their work continues to be so good because it pushed the boundaries of respectability.”

With ongoing debates concerning book bans and educational standards, McCaskill stresses the importance of these women’s works.

“There is no American story without the voices of Southern women,” McCaskill said. “There is no American story without the voices of women, and I’ll leave it at that.”

Gabrielle Gruszynski is a third-year student majoring in English and journalism.

Show Comments (0)