When Sahana Parker, a fourth-year majoring in astrophysics and geography, was a first-year student, she saw people on bright orange trikes whizzing across campus and wondered what in the world they were doing.

She knew she had to find some way to get involved with that program, whatever it was.

“I saw people riding the orange trikes around and I was so jealous. I was like, ‘I want to be them … I have to ride that bike,’” Parker said.

As a fourth-year student, Parker is now the lead intern for the Campus Composting Program, a student-run initiative housed in the University of Georgia (UGA) Office of Sustainability that collects food waste from over 100 sites across campus, according to the program’s website.

Now, 2023 marks the 10th year of operations for the program, according to Justin Ellis, program manager at UGA’s Office of Sustainability. He oversees the Campus Composting Program, and noted that it is one of the longest-standing student-run programs. He credited the longevity and scale of impact of the program to its collaborative, team-oriented nature.

“We have really focused on how important it is to structurally build the capacity of a team and build the definitions of what the different roles are,” Ellis said. “When you’re pushing something good, people want to be involved in it.”

Why It’s Newsworthy: With increasing concerns about how food waste contributes to the mounting climate emergency, the Campus Composting Program tackles the problem through a highly visible, long-lasting initiative that continually seeks to expand services and make composting more widely available to the entire UGA population.How Did We End Up With Orange Trikes?

The program didn’t always have a flashy symbol.

Beginning as a grant-funded project from the Office of Sustainability, the Campus Composting Program was run by a small group of student volunteers that picked up composting at various locations across campus in UGA Facilities Management vehicles, according to Parker.

“That program did really well, so they kept expanding it,” Parker said.

As a new means of transportation, the program began utilizing electric bikes with specially-made carts attached to the back of the bike, Parker said.

In 2019, the program began using the orange Radburro trikes — a symbol widely seen across campus, Parker said.

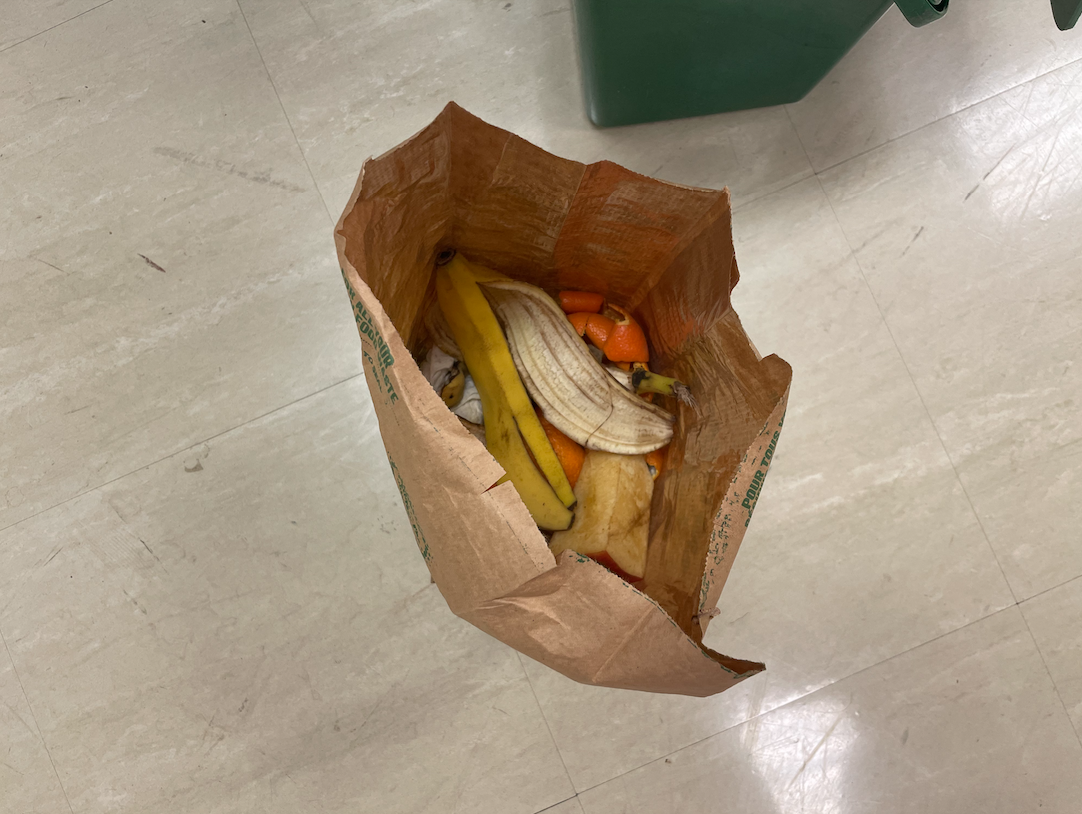

Today, Campus Composting interns ride the trike along different routes across campus to collect compost and bring it back to the Chicopee Building off Broad Street, Parker said. From there, the compost is collected by Athens-Clarke County and processed in their commercial composting facility.

Campus Composting interns like Kali Lyons service their routes weekly. Lyons said that the program is opt-in.

For Lyons, interacting with people who requested the bins and are enthusiastic about composting is a highlight of the program.

“I think that’s one of the best things is like, getting to talk to people and they’re just really excited about getting their compost bin,” Lyons said. “People actually care about this … and it feels good.”

Lyons said that recycling food scraps through composting is one small part of a larger movement towards sustainability that should include many different efforts and be accessible to anyone who wants to participate in living a greener life.

“I personally don’t like the very exclusive, like, ‘If you don’t use this metal straw every single time you’re a terrible person and you don’t care about sustainability,’” Lyons said.

Why Pedal Across Campus to Pick Up Food Scraps?

In fall 2022, the Campus Composting Program collected approximately 4,000 pounds of food waste and other compostable materials across campus, according to Parker.

Laura Ney, Athens-Clarke County Cooperative Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources agent, said she considers any amount of organic waste diverted from landfills and turned into nutrient-rich material as a success.

“4,000 pounds is 4,000 pounds; it’s not in the landfill,” Ney said.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, methane is an incredibly potent greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere, which contributes to climate change.

Diverting organic material, Ney said, has become increasingly important. She said that this category of waste is one of the costliest things to manage in the landfill and is also the source of the majority of methane emissions from landfills.

“Just keeping as much organic material out of our landfills as possible actually has an impact on global warming,” Ney said.

Equally important, Ney noted, is the attitude changes or questions that are often prompted by the visibility and longevity of the program.

“Just people being aware that there’s a composting program makes people ask, ‘Well, why is there a composting program?’” Ney said. “I think even just the fact of it existing 10 years has probably raised a lot of awareness beyond the weight of compost or matter that they’ve kept out of the landfill.”

More Progress To Be Made, Even After 10 Years

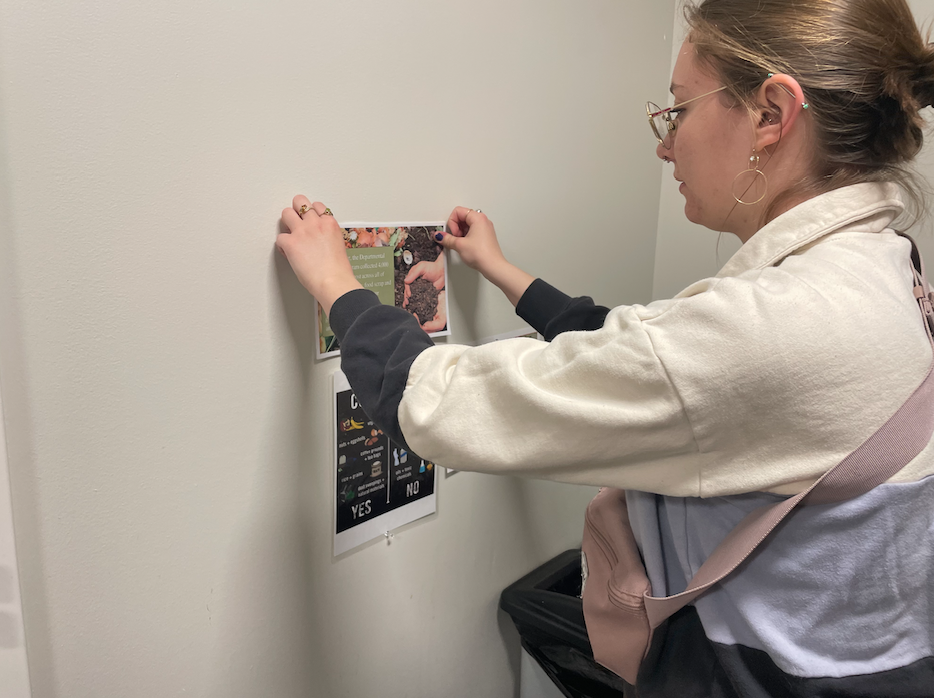

Even after the program has reached 10 years of diverting food waste from landfills and turning it into nutrient-rich material, Parker said she is currently working on a project to drive composting participation at the program’s bin locations.

Using behavior psychology principles, she designed a series of signs to be hung above certain bins across campus. Some show encouraging messages, some have messages expressing disappointment for not meeting the composting amount from the previous week and others have neutral, data-driven messages.

Parker said she hopes that adding to the existing signage above each bin will force individuals to face a conscious decision about where to put their organic waste and facilitate more composting.

“We’re just testing out what kind of techniques would work well,” Parker said. “Even if we could add one more sign that would increase people’s usage of the bins, I think it’d be pretty useful.”

Ella Filston, waste reduction coordinator in the Office of Sustainability with Waste Reduction Services, said that education and outreach are other crucial initiatives to expand the program and its impact. She noted that people understand the importance of recycling other materials, but don’t see the harm in throwing organic waste into the landfill.

“I think it’s really important to tell people why we’re doing this,” FIlston said. “I hear people say all the time, ‘Well, I get that plastic persists for hundreds of years. But who cares if I throw my apple core in the landfill?’” Filston said.

This compliments Filston’s other goal of adding widespread composting bins across campus–not just in break rooms, kitchens or other locations that are frequently staff- and faculty-only, and inaccessible to students. Eventually, she said, she hopes that an attitude of reuse becomes so widespread at UGA that a trash can is no longer necessary.

“Ideally, we go from the two bins we currently have–trash and recycling–to three bins–trash, recycling and compost–back to two bins, compost and recycling,” Filston said. “At some point, I’m looking for a world and a UGA where there isn’t a trash can.”

Parker echoed the hope that composting becomes more widely available for UGA students in particular, because she said they could have the biggest impact if this plan is implemented, particularly since they are interested in easy ways to contribute.

“It just makes me frustrated though sometimes because I feel like students have such a capacity to contribute to that, and most of our bins aren’t in an accessible location to students, it’s kind of hard to tell people about the program,” Parker said.

The Goal is … to Not Exist? Wait, Really?

Though the Campus Composting Program has been in motion for 10 years, the team agreed on an unconventional goal: they don’t want to see it around 10 more years from now.

They said they are aiming for this not because they think it needs to be retired, but because they hope that the commitment to composting outgrows what they can handle. Filston said she hopes composting becomes so widespread and normalized that it becomes absorbed by UGA facilities management.

“In 10 years, I would love for compost collection to be so institutionalized that a building service worker just empties the compost bin the same way they empty trash and recycling,” Filston said.

Parker acknowledged the peculiarity of this goal, but said she changed her mindset about the real long-term goals for the program once she realized the importance of growth in this initiative and other projects.

“It’s kind of weird to think about, that you’re working to be obsolete. But I think that’s the goal of a lot of sustainability programs, so it’s kind of a recurring theme there,” Parker said.

Lyons said that she is hopeful that, with expansion efforts, the program will outgrow the trikes and get larger institutions like Athens-Clarke County or UGA to collect the compost from each building because of the sheer size of the material composted.

“You just have so much volume that you couldn’t have enough people to do it by trike. I would really like to see that one day. I think there’s potential for it,” Lyons said. “That would be crazy. I think it’d be dope.”

Anna Chapman is a senior majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and obtaining a certificate in public affairs communications at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)