As the smallest county in Georgia with the oldest public university, Athens-Clarke County utilizes revitalization to balance the community’s historic value with modern development.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Across Athens, visible change is evident, as new properties are constantly under construction and old buildings are being repurposed for new use.

Before redevelopment construction can even begin, there are considerations of historic preservation and sustainability. The process of planning is a long one. Rehabilitation is a multifaceted process involving the development of new properties and the renovation of old ones, which often results in increased home values.

Rehabilitation to Historic Properties

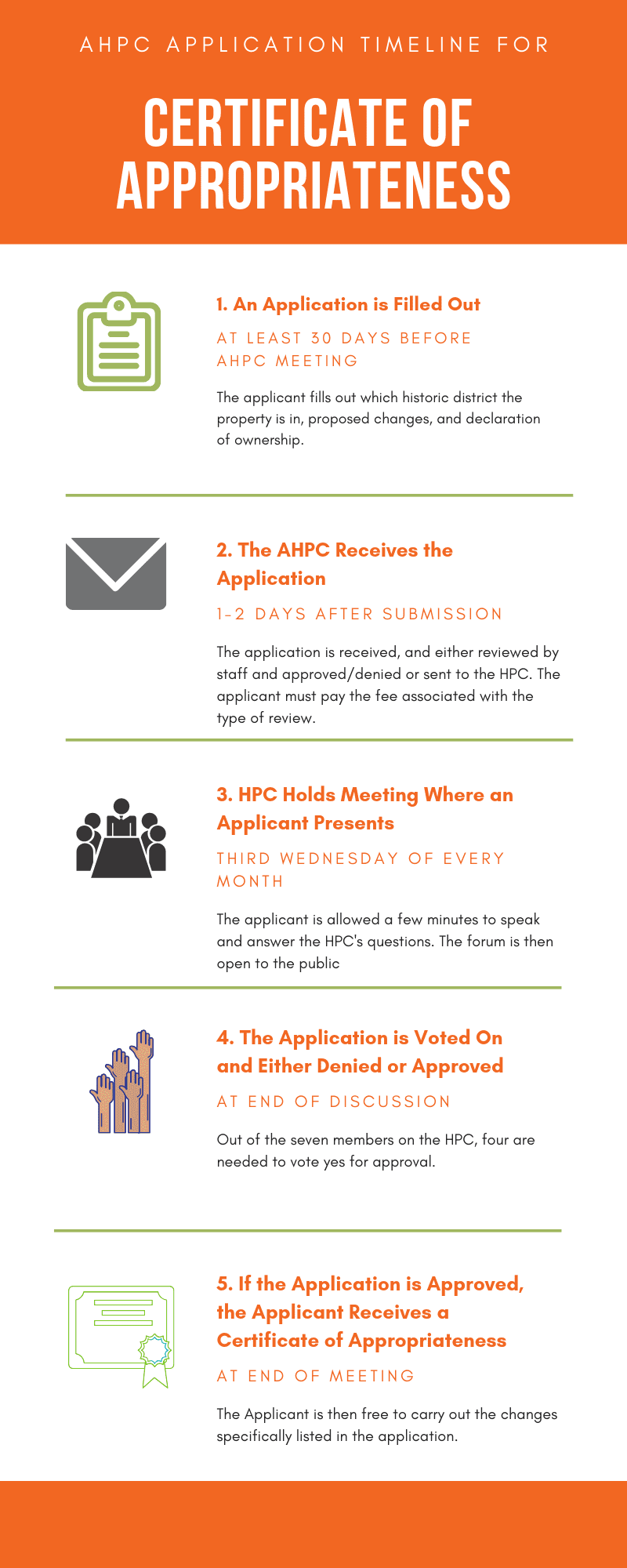

The Athens Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) received a total of 133 applications for design changes to historic buildings in 2017 and 118 of those were approved. While most requests are accepted, there are many challenges in terms of processing fees and time that make rehabilitation in Athens a more complex process.

Before revitalization of any property is carried out, an owner or developer has to find out whether the property is historic or not. There are a total of 15 historic districts in Athens, and many have different guidelines.

“The types of projects requiring review are the same for both contributing properties and non-contributing properties, though what is considered appropriate may be different,” said Amber Eskew, preservation planner for the HPC.

Contributing properties are those that are considered to contribute to the historic character of the area while non-contributing properties do not. Several properties in the area fall under one of those categories and thus, must go through the commission for approval.

Changes visible from the street are ones that are most heavily regulated. The new Chick-Fil-A, opening downtown across from the University of Georgia arch, had to submit several applications to the HPC for different storefront modifications, as the historic building has housed various restaurants and businesses over the past century.

The changes were all eventually approved, but the process did take a bit of time.

“The deadline to submit a Certificate of Appropriateness [application] to go before the HPC is 30 days prior to the hearing, so [it takes] at least a month but maybe more if the application was turned in before the deadline,” Eskew said.

There are also different fees for an HPC application, ranging from $50 for minor projects to $500 for some of the more major developments.

Minor design changes can bypass the HPC and go straight through to “staff review,” which take up to three business days, but most applications are sent to the HPC.

The University of Georgia Alpha Phi Sorority filled out an application this past spring for the historic house they are renovating on South Milledge Avenue. The proposed change was to pave the driveway with asphalt as opposed to concrete. The application for Certificate of Appropriateness (COA) was sent to the HPC and subsequently denied.

“Had they been asking to change the material to one that was considered appropriate by the design guidelines and fit with the historic character of the area, then staff could have approved it,” said Eskew.

According to HPC bylaws, asphalt is not considered appropriate, which is why the application was sent to the HPC instead of going to staff review.

“They could seek approval from the HPC to determine if there were circumstances that made the material appropriate in that case that were not generally true,” said Eskew of the application.

There are seven members on the HPC, all appointed by the mayor and the commission. They meet once a month and oftentimes hand down unanimous decisions, but there are some applications with which there is more disagreement.

“The harder cases to review are when a proposed change can be seen as attractive but [not yet] in line with the design guidelines,” said Eskew. “The HPC must follow the principles of the design guidelines in their decisions and sometimes that goes against their initial feelings on a design proposal.”

Bigger projects require multiple applications. Alpha Phi submitted another application in July to pave the parking lot on the property. Structured gravel was approved, but the paving was not.

“For larger projects, it is common for design changes to cause a return with a new application as the bidding is done and true construction costs or engineering happens,” said Eskew.

The historic Alpha Phi house is scheduled to open in 2019 after renovation.

Sustainability and Redevelopment

As older and sometimes historic homes get redeveloped and remodeled in Athens, another major factor is sustainability. While some sustainable practices have always been around, energy efficient and green features in houses have steadily risen in popularity.

As more and more consumers look for environmentally conscious homes, firms that specialize in this type of construction, like Architectural Collaborative, have more opportunities to build new spaces and renovate old ones in a responsible way.

“I would definitely say it’s trending in the field of architecture, you know just to do the right thing, to consider green and responsible practices and materials,” said Lori Bork Newcomer, co-founder and architect at local firm Architectural Collaborative.

With housing supply as limited as it is in Athens, some buyers buy older homes, some with historic value, with plans to renovate. Firms like the Architectural Collaborative renovate these homes, and make them more energy efficient while preserving their heritage.

“One thing that matters to us is maintaining our cultural heritage. When you go into a new development and you see all new construction, it doesn’t have any of the character that a space with mixed ages in the housing stocks would have. To me, it’s important to keep the cultural heritage, to have varying ages of homes,” Newcomer said.

Above is an example of a current project on a historic home that Architectural Collaborative is set to begin construction on. They recently completed the design phase, and have sketched the projected result. The next step is to start the redevelopment process.

However, the process of design and redevelopment is lengthy and can end up costing buyers as much, or more, than the price of a new home.

“Almost every place is reworkable, it really depends on the integrity of the structure, that’s the first step. It’s really about finding the right kind of client, one who is ready to invest in the culture of an older home, because it’s really about the character and the history,” said Newcomer.

While renovating an older home can be expensive, investing in sustainable construction can greatly reduce a home’s energy and water costs. Decreased utility bills each month can make a large impact in savings over time, which is a big draw for some homeowners.

Architectural Collaborative has two LEED certified architects, which means they are qualified to build homes according to the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design standards. These homes are accredited with a LEED certification, which is the most widely used green building certification in the world.

LEED certified buildings must adhere to a strict set of principles that determine construction, resource and energy practices. These principles ensure that buildings have been designed and built in the most energy efficient way.

One of the local leaders in green construction is Hotel Indigo Athens, a boutique hotel in downtown Athens, which boasts one of the world’s first LEED Gold certifications for a hotel. This certification is one of the highest levels of energy efficiency a business can achieve.

“We actually use about 33 percent less energy than a traditional hotel, which pretty drastically reduces our costs,” said Abby Hicks, the director of sales at Hotel Indigo Athens.

The hotel, which opened in 2009, emits less greenhouse gases than a traditional hotel, and has reduced its water consumption by 35 percent.

“When our owners were looking to build the hotel, they understood that it could impact the community and the environment in a positive way, by setting this standard for the LEED certification. That mattered,” said Hicks.

Since the hotel’s opening in 2009, the next building to receive certification in Athens was the University of Georgia College of Environment and Design’s Jackson Street Building in 2013.

Infill Impacts and Possibilities

As towns grow and change, developing new areas and buildings can just be part of the process in making the towns more habitable. In some cases, however, it makes more sense to build on what has already set a foundation for a town.

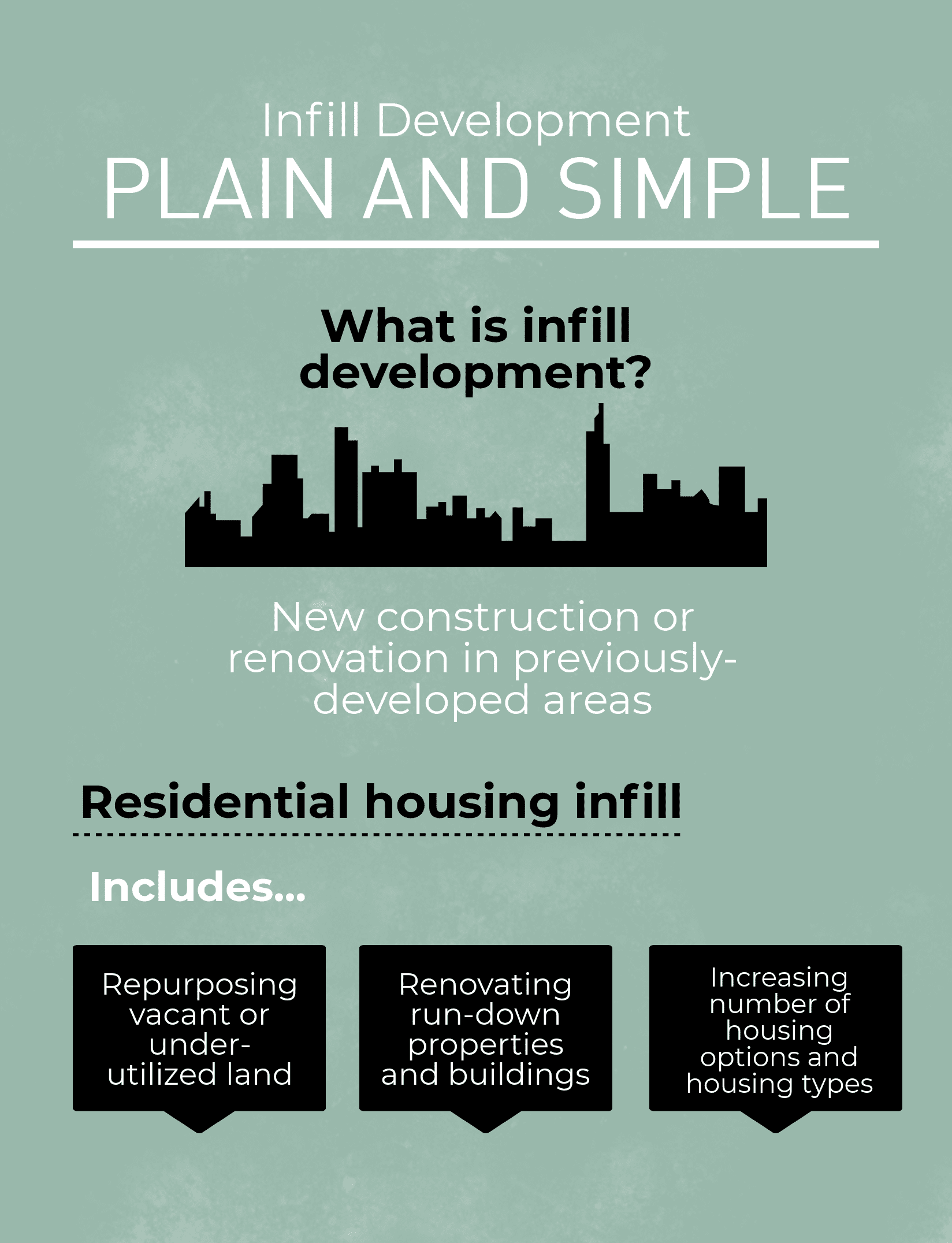

Infill, or infill development, is a way to do this. The term is hard to pin to one definition, but it can loosely be described as new construction or renovation in previously-developed areas. This mainly entails building new homes or businesses in existing, underdeveloped land but can also include renovating run-down properties.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency in a 2014 study, the demand for infill housing has grown and is expected to grow even more.

A big part of this is the change in demographics of people who are likely to purchase a house. Infill projects for the baby boomer generation — namely senior living communities — are popping up more and more.

On the other side of this coin, the number of single-person households has increased rapidly. As of the 2010 United States census, single-person households made up 27 percent of all households. In some more densely-populated cities like Atlanta and Washington, D.C., this figure was more than 40 percent.

In these cases, infill housing is a smart choice, both environmentally and economically. But what does infill mean for a town like Athens, which is changing so rapidly and yet has a history that many don’t want to alter?

Infill housing is a topic that has been discussed in Athens for over a decade. A 2008 in-depth study on infill in Athens identified possible issues and strategies that infill housing would bring to the Classic City.

Logistic issues included compatibility with existing architecture, space utilization and meshing with specific design standards in Athens.

The study did lead to changes, but did not result in a passed infill housing ordinance.

In Athens, there are both ardent supporters and opposers of infill, one of the reasons that the ordinance did not pass.

A big problem that many Athens locals have with the prospect of infill housing in town is the possibility that it could detract from historical sites or lead to the gentrification of neighborhoods. This is still a concern, even when the 2008 study stated Athens’ historic districts “allow and even encourage contemporary infill construction” with careful planning and construction. Infill could even possibly lead to the displacement of existing owners due to an increase of property values and taxes.

Even so, infill housing can have its advantages. Repurposing land that doesn’t have a current purpose can lead to a more cohesive town design and open up space for more potential housing. For example, a plan was created in Portland that would connect old residential areas and added infill properties by using underlying “rhythms” in the buildings’ designs.

According to the EPA, another benefit of infill is its economic incentives. A combination of reduced infrastructure costs for amenities like public sewerage, streets and other transportation facilities and better economic returns could mean that infill will actually be the smartest way to approach housing as the markets change.

While the state of infill in Athens is still very much in the air, the conversation is happening. The proposed ordinance that was not passed was one attempt to bring infill housing to the Classic City, and it will likely not be the last.

The Effects of Revitalization and Redevelopment

According to Athens-Clarke County Chief Appraiser, Kirk Dunagan, over the past three or four years housing prices have been steadily increasing—and it’s not just because of the economy.

“Starting about in 2012, we were seeing some steady increases—just kind of nominal—things were starting to improve,” said Dunagan. “But over the past few years we’ve seen some pretty substantial changes in property value.”

Besides a general increase in the economy, Dunagan attributes this rise in housing prices to revitalization and redevelopment happening in neighborhoods across Athens.

“When you do put some work into your house and renovate it, you generally get a pretty good price for it, and we’re seeing quite a few people do that as well—in addition to the infill housing,” said Dunagan.

Not all people who are renovating their homes are staying in them. Dunagan has noticed that many homeowners are renovating their homes in an attempt to sell them for a higher price.

Dunagan said this overall price increase is happening all across Clarke County, but some neighborhoods are seeing more substantial price increases. A few examples of these neighborhoods are Boulevard, Cobbham and Talmadge (or Normaltown).

From 2009-2018, the average price of a home in Boulevard has increased by 149 percent, in Cobbham by 311 percent and in Talmadge by 84 percent, according to data from the Athens-Clarke County Tax Assessors and Appraisal Office.

According to the same data, in just a year (2016-2017), the overall price of a home in Athens increased by 6.37 percent.

Graphic by Becca Beato

When it comes to anticipating the future market, Dunagan doesn’t know what’s going to happen. In the ACC Tax Assessors and Appraisal Office, the trends they notice are from past data. They estimate the next year’s prices by looking at the data from the year before.

“We’re always kind of looking back not necessarily looking forward…but based on the last few years we’ve certainly seen those prices go up,” said Dunagan.

Lauren Funk, Lydia Megdal, Claire Cicero, and Becca Beato are seniors majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.