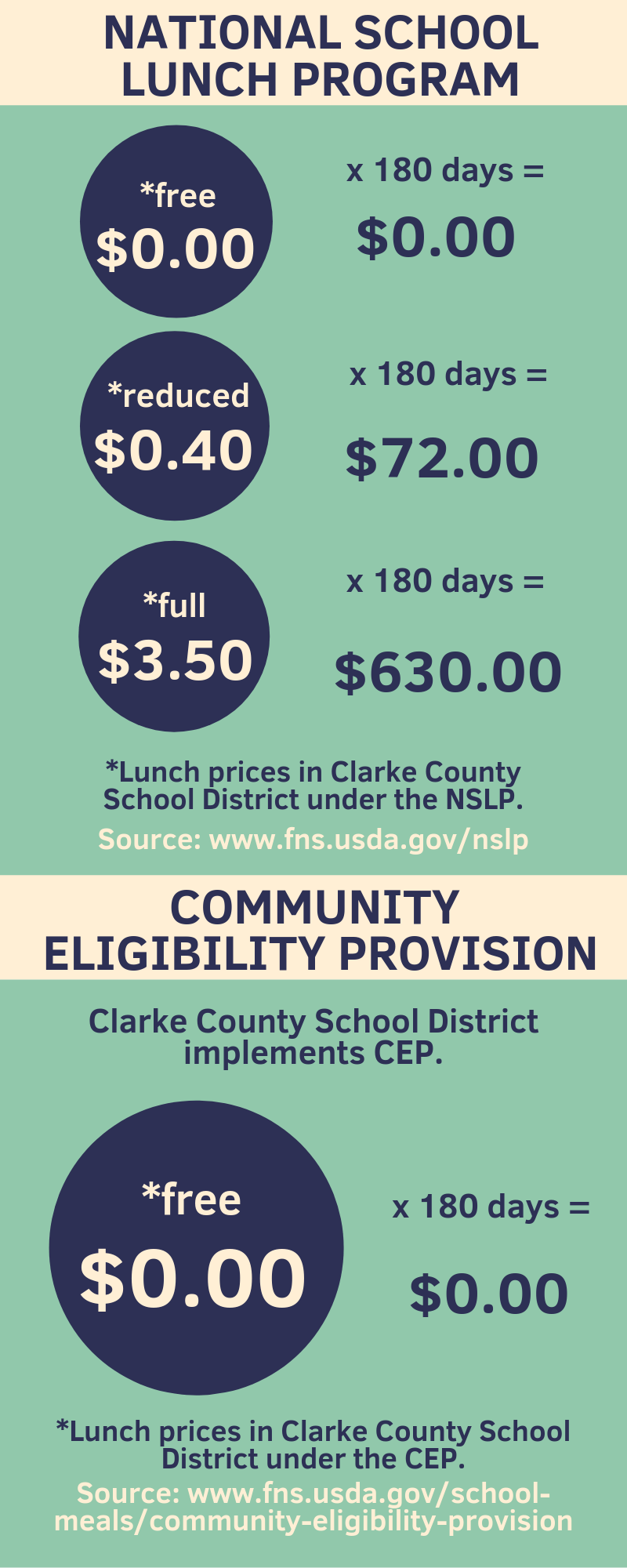

Free, reduced-price and full-price lunch designations—nationwide categories created by the National School Lunch Program—have no place at Clarke County School District in Athens, Georgia.

That’s because the 21 public schools in the district provide free meals to all students, regardless of financial need.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Tens of millions of children receive meals through the National School Lunch Program, many of whom eat both breakfast and lunch at school. Clarke County School District qualifies for the Community Eligibility Provision, which provides free school meals to all children, because of Athens’ poverty rate—26.6%. CCSD implemented the program in 2015, but it is not guaranteed forever, and the district must reapply every four years. The surrounding counties do not have enough financial need to qualify for CEP, but Madison County School District implements a different federal program—Provision 2—to provide free breakfast for all students.

Every public and nonprofit private school in America operates under NSLP, in which the requirements needed to qualify for free or reduced-price school meals are based on both family income and categorical eligibility. Such eligibility includes involvement in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, as well as children who are migrants, homeless, runaway or in foster care.

However, there are federal provisions created for schools with greater financial need. One such arrangement is the Community Eligibility Provision, which was developed by the Obama administration under the Healthy, Hunger-free Kids Act of 2010.

Implementation of the program requires each school, group or district to provide an established claiming percentage of 40% or higher of students identified as categorically eligible for free school meals. This information is gathered through census data, eliminating the need for application paperwork.

According to Paula Farmer, school nutrition director for Clarke County School District, the district adopted CEP in 2015 because of the high poverty rate in Athens, which is currently 26.6%.

“I will say I love CEP, simply because there’s no stigma,” Farmer said, “and we can … focus on why we’re here, and that’s to feed children.”

Since it is a federal program, local taxpayers are not directly affected by the school district’s decision to provide free lunches for all students. Kirk Smith, a 57-year-old resident of the district with no child in the school system, believes the decision was smart, even though he only indirectly contributes to its application through federal taxes.

“The program, I think, is good and needed,” Smith said. “To pretend that we don’t have an issue with that in our country, it would be just keeping your head in the sand.”

Instead of district taxpayer dollars, the district is reimbursed by the federal government for the free meals they serve based on its established claiming percentage. Clarke County School District receives $3.50, $3.10 and 41 cents for every meal served that would have been free, reduced price and full price, respectively.

Even though every meal is reimbursed, the amount is sometimes not enough. Farmer explained that it costs much more than 41 cents to prepare a meal, as milk alone costs 27 cents—and that doesn’t include labor.

“School nutrition is self-operating, meaning the money that we receive from reimbursement for the meals that we serve, the funds are used to pay salaries, purchase food and purchase equipment,” Farmer said.

One limitation of the program is the possibility of schools running out of food as a result of the limited stipends they receive.

Hunter Yelton, an 11th-grader at Clarke Central High School, has felt the effects of such limited resources. Yelton has the last lunch period on Wednesdays and said he once received only the chicken of the spicy chicken sandwich meal instead of the full sandwich with buns because the cafeteria had run out of buns earlier that day.

However, Yelton emphasized the positives of the free school lunch program far outweigh the negatives.

“It’s really good just to know that, you know, you have something that’s there for you,” Yelton said. “And I think it does help a lot of students out.”

The system also eliminates any potential food charges, meaning there is no outstanding debt from school meals for students at the end of the academic year. In districts without CEP, the accumulation of unpaid lunches leads some schools to take extraordinary measures to have it paid back.

However, CEP runs on a four-year cycle and requires schools to reapply after every cycle with a renewed eligibility claiming percentage of qualified students, so any school is able to begin—or stop—implementing CEP depending on updated census data in the district. And schools who get close to the 40% mark, but do not quite hit it, are not eligible for the program.

While this system works for Clarke County, Farmer said not all districts are able to participate in CEP because of the differing income rates of each county across the nation. Even though a community might not meet the set guidelines, she said, there may still be pockets of poor families struggling in the district.

“When there’s hunger, I think it goes without saying that sometimes our students rely on the school meals that they receive, and hungry children don’t learn,” Farmer said. “So, they play a huge role in the success of our students in the classroom as well as outside of the classroom.”

Neighboring school districts in the surrounding counties—Oconee, Oglethorpe, Barrow, Jackson and Madison—have lower poverty rates and do not fully qualify for CEP. Madison County implements a different free school meal program called Provision 2 for breakfast only.

Other programs, such as Provision 2, exist to provide free school meals to students, but the details of eligibility and funding can vary. CEP determines eligibility through census data and receives full government funding all four years, but schools implementing Provision 2 require financial need applications from each student to establish a basis for partial government reimbursement during the first year of its four-year cycle.

CEP and Provisions 1, 2 and 3 all reduce the application burden placed on families by the National School Lunch Program by limiting the amount of applications needed to determine financial need over a period of two to four years. Though the reduction of paperwork lessens parental burden, a district’s financial data may not accurately represent the needs and struggles of families at every school.

“The system’s broken,” Farmer said. “No matter what state you live in, there are issues for parents who can’t afford school meals.”

Gabriella Audi is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)