Turkey legs, funnel cake and lemonade are just a few staples at the Georgia National Fair in Perry, Georgia. Cindy and Junior Jimenez, siblings from South Georgia, always make it a point to each get a turkey leg. As they attended the fair for the second year in a row, they decided to take advantage of the fair food and drink that only comes around once a year.

People often consider what delicious food they’ll get at the fair, but many overlook the waste associated with the treats. Each turkey leg and lemonade comes with packaging that, as soon as it is consumed, goes straight into the nearest trash can. In 2018, that turned into 168 tons of trash. According to George Neal, the Georgia National Fair’s Physical Plant Director, this year’s total has yet to be calculated, but 2018’s total is about average.

Finding a Place for Waste at the Fair

According to Neal, the 2019 fair had a record 565,000 people in attendance. To handle the waste created by a fair of this size, 250 trash cans are placed every 100-150 feet on both sides of the road throughout the fairgrounds. “Anywhere you’re standing you can see a trash can, so that will try to deter people from just throwing it on the ground,” said Neal. There are crews that walk around the fairgrounds picking up litter and changing out the trash cans as they get full to keep ahead of potential overflow.

The layout of the fair allows for certain areas of the fairgrounds to be more easily controlled. Most of the vendors whose sales create waste are located in one general area, so extra trash cans are placed around the vendors and eating areas to compensate for a higher congestion of foot traffic and trash. Once the trash is collected, Advanced Disposal is hired each year to haul the trash away.

Some vendors even provide their own trash cans to supplement those provided by the fair. Kevin McGrath, who owns the vendor chain “The Best Around,” sets out a few trash cans of his own around the designated seating area for his customers.

“This is where our customers sit and eat their food, so we put a couple extra out just so they have one close by,” McGrath said.

McGrath has his own employees change out the trash bags, simply leaving the full bags for the crew to pick up at a later time. However, McGrath said the fair crew sometimes change out the bags in his trash cans in addition to the “Keep America Beautiful” donned trash cans the fair provides. “They empty those for us too a lot of the times.”

Vendor Roles in Waste Management

Vendors apply to be part of the Georgia National Fair as early as February. According to the Georgia National Fairgrounds & Agricenter’s Exhibitor’s Guide, they are required to follow guidelines regarding space regulations, advertising, electricity and sound equipment. The only regulation regarding waste is that they will “sweep all refuse from their booths to the aisles after closing where it will be picked up by the janitors provided by the Authority.”

The vendors are free to sell and package their food however they want, as long as it complies with the Houston County Health Department regulations. According to Neal, the amount of waste can’t be regulated because it depends on the number of people in attendance. “Most of the food they serve is a grab and go type food, that’s usually with a piece of paper or something like that,” Neal said.

Of the 53 vendors in attendance in 2019, most were not willing to talk about the types of packaging they used for their food or its possible environmental impact. McGrath, one of the willing few, said most people are conscious of typical food packaging waste, but at an event like this “you’re going to have some kind of waste. Entertainment has some falls to it.”

McGrath’s booth uses deli-wrap paper to serve food. Despite making an effort to not bag everything or use Styrofoam containers, he said “there’s always room for improvement, without a doubt. Nobody can say there isn’t.” While he can’t put a number on how much deli-wrap paper the booth uses, he said they “always try to waste as little as possible.”

Joe Dunlop, the waste reduction administrator at the Athens-Clarke County Waste Reduction Center, said the deli-wrap paper isn’t ideal. He instead suggested compostable wears, which according to Commit to Green, are “single-use disposable food service ware items that are manufactured from materials that degrade rapidly and safely into a valuable soil-like material when these items are sent to a commercial or municipal composting facility along with other compostable materials such as food scraps and yard waste.”

That would require trash cans and composting cans, and everything would go into one of those two cans. “They could get everything compostable serviceware and then collect all those compostables. It then goes off to a composting operation,” said Dunlop. “We could take it in Athens. Although I don’t know if they want to ship it all that way up here.”

Recycling as a Potential Solution

Like most large events, the vendors who sell beverages offer cheaper choices in a small paper cup or a more expensive choices in a plastic refillable cup. The plastic cups are a popular choice among fair-goers. Everywhere you look on the fairgrounds, someone is holding a plastic cup.

Cindy Jimenez too noticed that most people at the fair throw their thick plastic cups away when they’re done using them. Jimenez and her friends, however, take advantage of the refills. “Some of my friends and I use them every year because of the refills.” Jimenez said. “I like to reuse them, I don’t throw them away.”

Junior Jimenez thinks that more people would be inclined to keep their cups for multiple days or even years if vendors were to lower the price of refills. “If they lowered the price of refills people could actually buy them,” Jimenez said.

Until people are more incentivized to keep their cups, they continue to be thrown away. While a solution could be to start a large scale recycling program at the fair, Dunlop said large events like these can only recycle if the infrastructure is there. Recycling centers not only have to be geographically close to the fairgrounds, but they also have to be equipped to handle the recyclable material and willing to be a part of the fair’s initiatives.

“It all depends upon the local will to do something different and the local infrastructure to be able to do something different, if they wanted to,” Dunlop said.

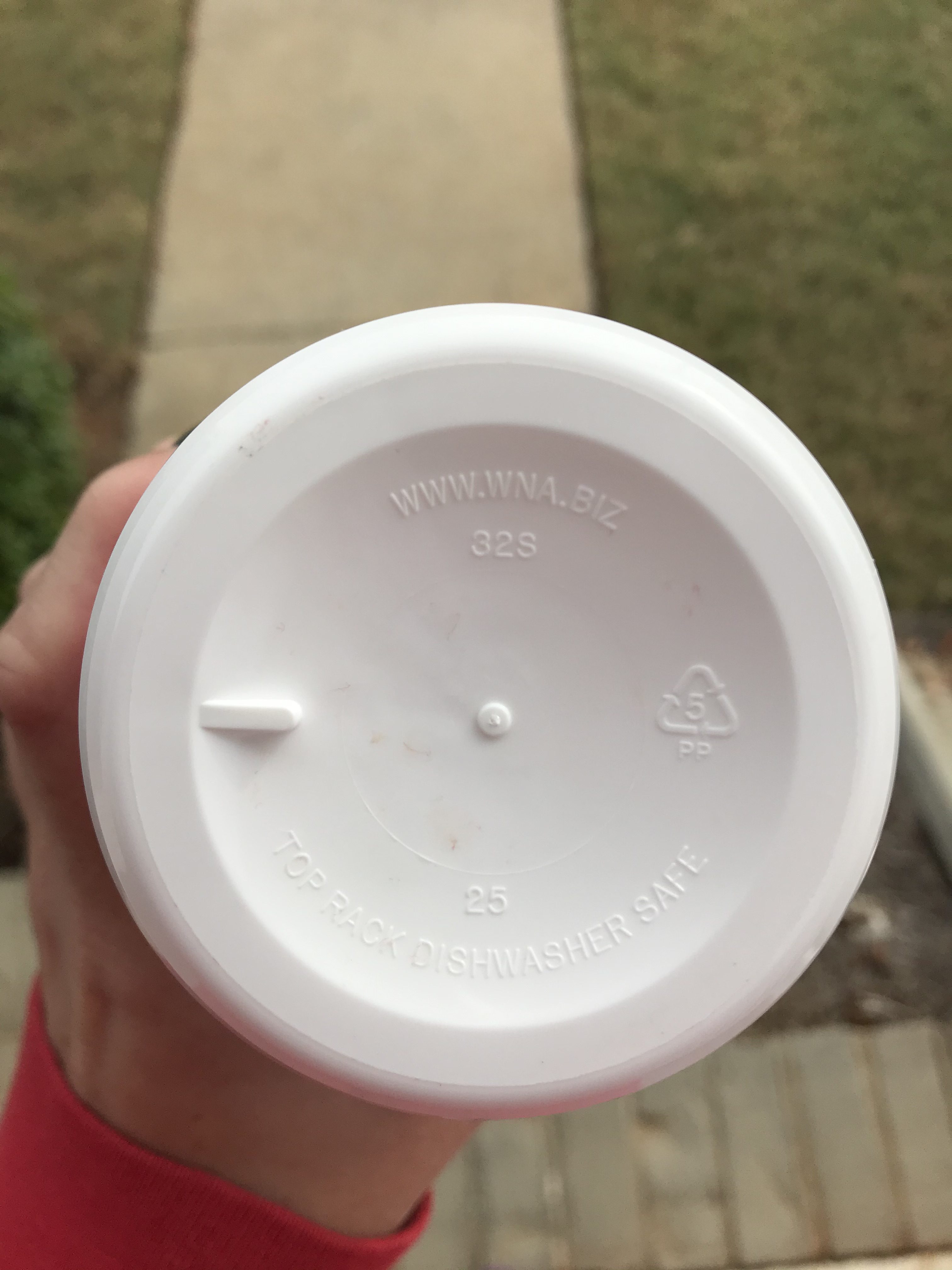

On the bottom of most plastic containers there’s a small number, usually inside a triangle. This number represents the type of plastic the item is made from. Most local recycling collection programs, according to Dunlop, only accept ones and twos. The fair’s plastic cups are fives.

Despite this constraint, the fair does recycle some. “We recycle all our cardboard but the commodity market is so low right now,” Neal said. “It’s hard, we’re actually storing all our cardboard.” This is the first year the company hasn’t bought it because “the market is dead right now.”

Perry is a physically large facility, which in itself creates an issue when considering recycling. “Somebody has to go around and collect all that stuff. It’s got to stay separated, it’s got to get to somebody who can do something with it in a condition that they can do something with it,” Dunlop said. “It then has to be bailed up and sent to a market. There’s a cost to all of that.”

There’s something to be said about needing the time and money to recycle. Even though the Georgia National Fair does put out bins for certain recyclable plastic bottles, according to Neal, people still end up using them as trash cans. “By the time we get through separating it all we have more labor than we can recover,” Neal said. “It’s not worth it to us, we can’t afford to do it and we haven’t found anybody willing to take the plastic with the trash to separate it themselves.”

Until the Georgia National Fair can find the funds and means to recycle food packaging waste items other than cardboard and plastic bottles, the fair will keep on running as is. It won’t stop individuals like McGrath from bringing back “The Best Around” or Cindy and Junior Jimenez from coming to get their beloved turkey legs and lemonade.

Emily Lanoue is a senior at the University of Georgia pursuing a bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in communication studies and a certificate in new media.

Show Comments (0)