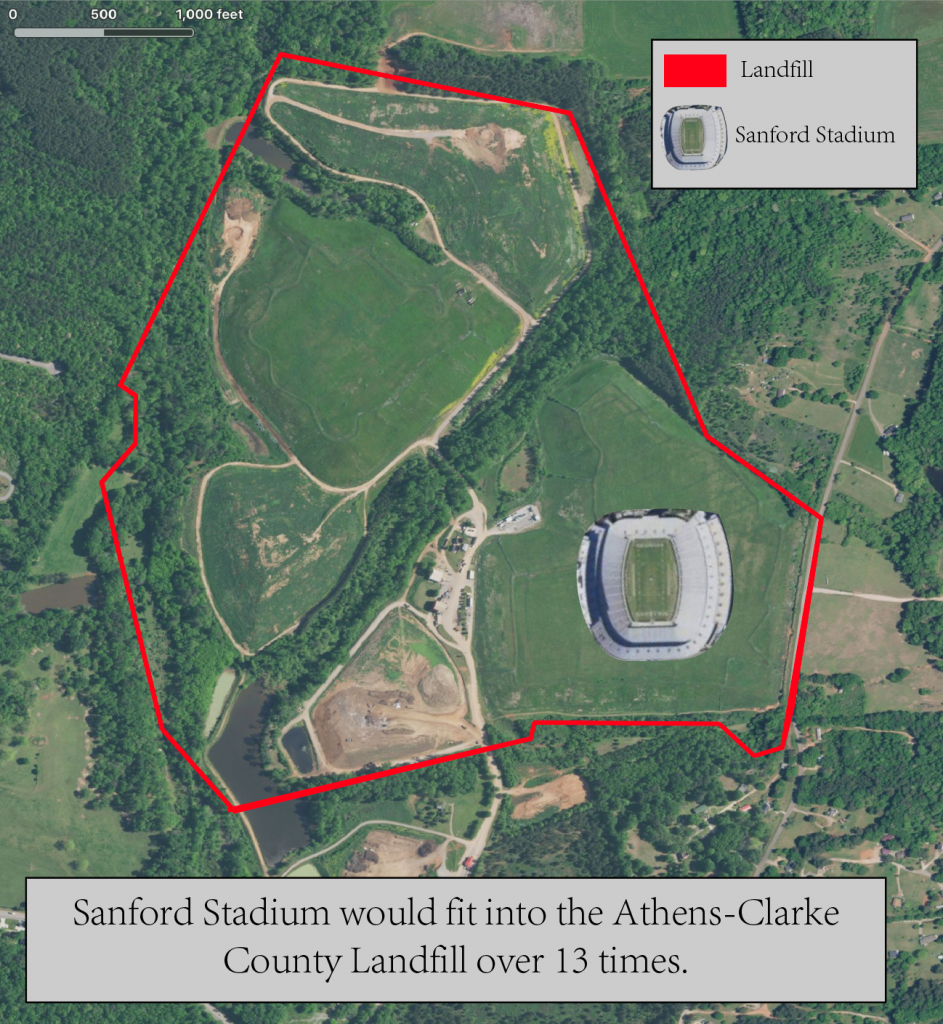

Approximately 300 tons of material is disposed of in the Athens-Clarke County Landfill daily. The average dump truck holds 12 to 14 tons of waste, so approximately 23 dump truck loads of garbage are dumped into the 289-acre landfill per day.

Yet, not all of it should be garbage.

“About 50% of what goes into the landfill is estimated to be recyclable,” said Athens-Clarke County Recycling Division Program Education Specialist Mason Towe. “And then about 30% could be composted.”

Towe hopes to eventually renovate the last 10–20% to keep it out of the landfill because the Athens-Clarke County Landfill is running out of space.

Composting and recycling are better alternatives than sending everything to the landfill, but they only work when done right.

Landfills are designed to store waste, not break it down. Yet, to make a dent, the public needs to be educated and more active, Towe said. “It honestly depends on how the community participates.”

The bottom line is, the Athens-Clarke County Landfill only has so much space.

In June 2008, Athens-Clarke County purchased 79 acres from Oglethorpe County to expand the lifespan of the landfill. The new site has “an estimated life of 30 years at current disposal rates,” according to a brochure created by the Solid Waste Department.

“Nobody wants a landfill in their backyard, so every time we expand, it’s getting a little bit closer to where you live,” Towe said. “Every time you put a little bit of trash in there, it is getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”

But space isn’t the only issue.

“Landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Methane, a greenhouse gas, composes 50% of landfill gas. Landfill gas is a natural byproduct of the decomposition of organic material in landfills.

Landfill Working Face

Momento360 | View and share your 360 photos and 360 videos, on the web and in VR

This is the working face of the Athens-Clarke County Landfill. Garbage trucks dump their trash here—about 300 tons a day.

“Methane is a potent greenhouse gas 28 to 36 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere over a 100-year period,” according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report (AR5).

The amount of methane can be reduced by throwing less garbage into landfills, and one way to reduce the waste in landfills is by recycling.

Recycling: Putting a Bandaid on a Bigger Problem

“We’re very fortunate in that Georgia is actually the number two state for industries that use recycled content after California,” Towe said.

Many industries located in Georgia purchase recyclables from the landfill. Novelis, an industrial aluminum company headquartered in Atlanta, recycles aluminum.

“Recycling aluminum saves 95 percent of the energy needed to produce new aluminum from raw materials and the energy saved from recycling one ton of aluminum is equal to the amount of electricity the average home uses over 10 years. That means you can make 20 cans out of recycled material with the same amount of energy it takes to make one can,” according to “Rethink Waste: Recycle,” a UGA Extension article.

Carpet manufacturers in Dalton, Georgia, the carpet capital of the world, use recycled polyethylene bottles. Strategic Materials, a recycling company with two locations in Atlanta, processes recycled glass.

In addition to being environmentally friendly, “Georgia mills using recycled content employ 7,000 people” according to “Rethink Waste: Recycle,” a UGA Extension article.

“The problem is everyone’s wanting to send their stuff to those same markets, so there’s a surplus of material and the value has really gone down,” Towe said.

The industries have become more selective of what they’re willing to take and process.

“We have to process it more, which is more expensive, so we’re spending more money to make less money right now in recycling,” Towe said.

Nethra Rajendran works with UGA dorms as a housing intern for the University of Georgia Office of Sustainability where she helps implement waste diversion tactics and recycling education programs to assist building service workers with recycling collection.

These programs help to save potential recyclables and money—if the recycling doesn’t get contaminated. If a truck is contaminated, its contents could be taken straight to the landfill.

“We don’t want it going up the line contaminating other good recyclables. Right now, we are between a 10-15% residual rate,” Towe said.

Meaning, only 10-15% of what is sent to be recycled is processed. A lot of people don’t know what they can recycle, Rajendran said. Rajendran also helps out with an event called Dawgs Ditch the Dumpster & Donate, where students can donate household items instead of throwing them away.

Yet, nearly 28 percent, or 2 million tons, of Georgia’s household waste could have been recycled, according to “Rethink Waste: Recycle,” a UGA Extension article.

However, Towe says recycling shouldn’t be our main focus.

“Recycling is not going to fix all of the waste reduction issues,” Towe said. “Waste reduction and reuse are the ones that we need to focus on a lot more. There is so much food waste in landfills that we have got to ramp up our composting.”

Reducing Food Waste Through Composting

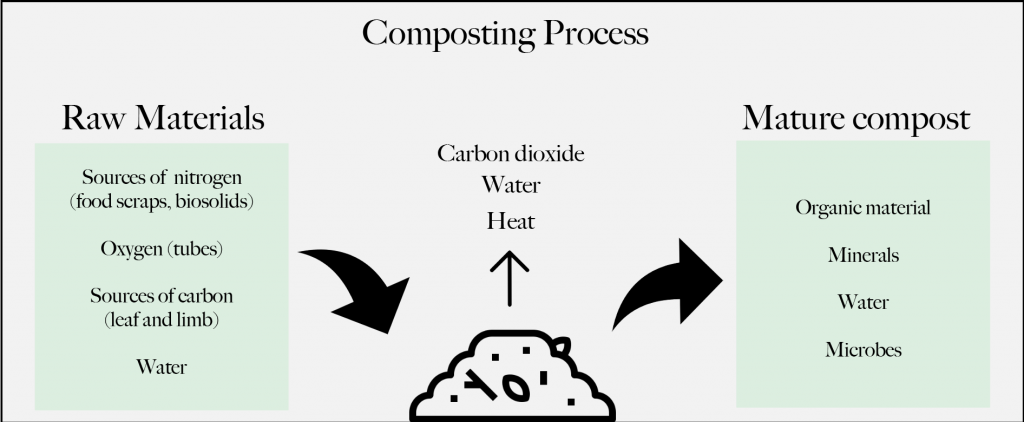

Composting promotes the favorable factors of decomposition by producing micro bacteria that break down food and waste into smaller pieces, according to a University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources article.

The Athens-Clarke County Landfill composts to decrease the number of yard clippings and food waste in the landfill.

Compost piles

Momento360 | View and share your 360 photos and 360 videos, on the web and in VR

This is the composting area at the Athens-Clarke County Landfill where food scraps, landscape refuse and biosolids are turned into compost.

“Landscape refuse, such as leaves, grass clippings and trimmings, accounts for up to 20 percent of the waste being placed in landfills,” according to Composting and Mulching, a UGA extension article.

Leaf and limb collection is offered to Athens-Clarke County residents to reduce the yard waste in landfills. Every six weeks, the Solid Waste Department collects correctly packaged grass clippings, pine straw, leaves and smaller tree limbs curbside.

Then, at the landfill, the tree limbs are put through a tub grinder to be shredded into mulch.

The mulch and clippings are divided into two separate piles of nitrogen-based material. The two piles of food scraps and biosolids are kept separate because organic certified farms cannot use biosolid compost under the Organic Certification.

Sometimes, non-compostable products get mixed into compost piles.

Mark McConnell, a retired commercial composter and the executive director of the Georgia Climate Change Coalition, said there isn’t an initial sorting system at the Athens-Clarke County Landfill to sift through the organic and non-organic materials.

A lot of compostable and non-compostable materials get mixed in together. This could lead to the whole compost pile being dumped into the regular part of the landfill.

“There is always a level of contamination in every ‘disposal’ stream, and in our inbound food scraps loads, it can fall in the 5-15% contamination range, depending on the source,” Towe said.

At the Athens-Clarke County Landfill, the compost is screened to collect large non-organic materials from the final product, but like every landfill, some things could get missed.

“I am pleased to report that we have not seen a significant contamination problem at the ACC Municipal Composting operations. I will say that it often looks much more ‘contaminated’ than it actually is, because there are compostable/biodegradable plastic wares in the mix, such as BPI certified bags, forks, plates and cups. Those look like trash, but actually will break down over a few cycles of composting,” Towe said.

“We have two different main piles; one nitrogen source is food scrap recovery. Let Us Compost is a local collector, and the county is now doing some local collection,” Towe said.

Let Us Compost collects food scraps curbside or from apartment doors in Athens, Watkinsville and Winterville. The weekly collection of a four-gallon bucket costs $25 per month.

Additionally, you can drop off your food scraps and compostable products to the landfill for $5 per five gallons dropped off.

“The other source is biosolids or sludge—the leftover concentrated nutrients from the water reclamation facility,” Towe said.

About 25% of the biosolids created in Athens-Clarke County are composted and the remaining bio-solids are sent to the landfill, according to a release by the Athens-Clarke County Public Utilities and Solid Waste departments.

The food waste, biosolids and yard clippings are mixed in a 3-to-1 ratio.

“We’re using aerated static piles, so we put the whole pile and that mixture all across these 80-foot pipes. About 60 feet of them have perforation,” Towe said.

The electric blowers—essentially bouncy house fans—force air through the piles.

Originally, Athens-Clarke County Landfill used a machine to manually turn and aerate the piles. The blowers take less time.

“What was taking three to four hours a day to turn all of that, now it takes a few hours to set this up and you let it sit for about three and a half weeks whereas the other piles took twice that long to turn,” Towe said. “It’s a lot less of a footprint, spatially, we can get a lot more material turned faster and back to the community to be used in gardens and landscaping, and we’re also able to take more material that would have otherwise been going in the landfill.”

As the microbes are breaking down the piles, they create a lot of heat.

“It gets up to about 140-160 degrees—it’s really cooking in there,” Towe said.

Once the piles cool down and neutralize in pH, they put the compost through the screener. Towe compares it to a giant sand sifter.

“Typically, we have a 2- or 3-inch screen on there and it sifts out any mulch or bigger pieces, rocks, things like that. The finer material will go out one side and that’s what we sell as the final product,” Towe said.

The bigger pieces leftover are put back and reused for the next batch of compost.

The screener doesn’t effectively sort through for the undesirable mixed contaminants found in the compost pile, McConnell said, so he encourages private residents to compost, as this takes some of the burdens from larger groups such as the landfill.

“I would say that the commercial composting operations and household backyard composting can easily coexist and complement each other in our community,” Towe said.

He doesn’t discourage backyard composting as it helps reduce the number of scraps produced while reducing waste bills, but the efficiency of the landfill is hard to beat.

“Household backyard composting is often more affordable because you’re not paying for a collection or processing service, but it is a lot more work and burden on the individual to process the material themselves. I’ll tell you from experience composting at my own home, it takes patience and work,” Towe said.

The landfill sold 1,885 tons of compost in 2018 and has already exceeded that amount for this year.

Athens-Clarke County is reducing waste a couple of tons at a time. Their goal is to reduce waste to the landfill by 75% by 2020, Towe said.

“We have plenty of space and plenty of land in the Southeast. In the United States, we have plenty of land, but at some point you have more people using more stuff with less land,” Towe said. “It starts adding up.”

Emily Lanoue, Jordan Meaker, Taylor Morain, and Tristen Webb are seniors majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)