At all levels of sports, transgender athletes are breaking barriers, simultaneously stepping onto the podium and into headlines across the world.

This past year, college senior CeCé Telfer became the NCAA Division II national champion in the 400-meter hurdles, and at the high school level, Terry Miller and Andraya Yearwood finished first and second, respectively, at the Connecticut state meet in the 55-meter dash.

As more transgender athletes rise to the top of their fields, the voices of their critics rise, too.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Particularly in women’s athletics, questions are popping up about how transgender athletes should qualify for participation, leaving administrations at the high school, college and professional levels to wrestle with a balancing act of fairness versus inclusion.

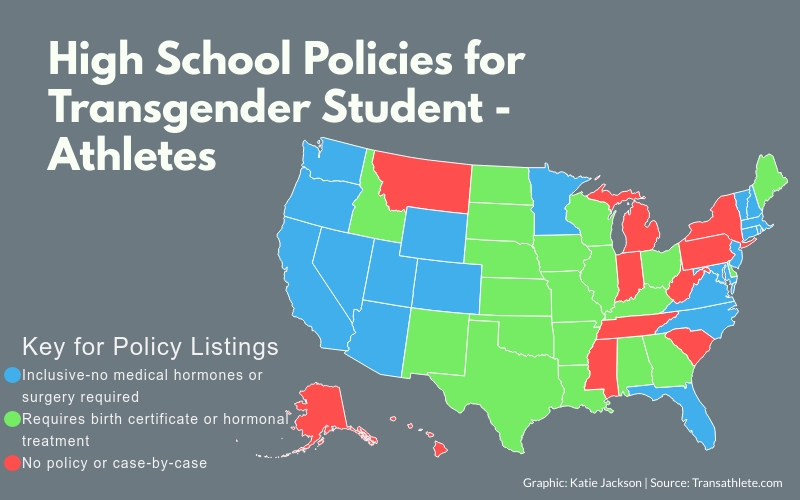

At the high school level, policies vary by state and school district. Transathlete.com is a website that was established in 2013 with the sole purpose of aggregating all of the different transgender policies across the nation. According to the site, 20 states allow trans athletes to compete with no restrictions; 20 have restrictions that make it harder for trans athletes to compete, such as requiring them to undergo hormonal treatment or to compete as the gender they were assigned at birth. As for the remaining 10 states, it either varies case-by-case or they have no policies in place.

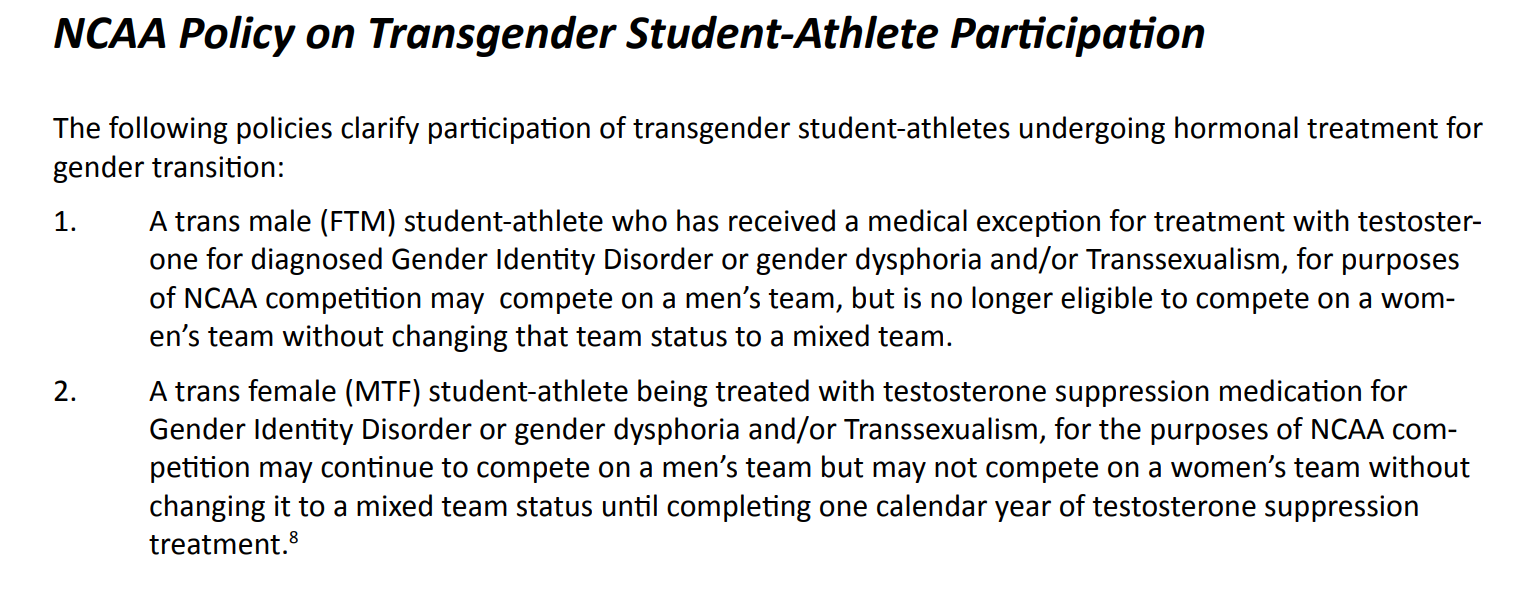

At the collegiate level, the NCAA has its own policy that is stated below:

Pat Griffin, professor emerita of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and author of “Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport,” played a key role in the process of adopting this policy. She along with Helen Carroll, director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR) Sports Project, were the co-authors of the NCAA transgender policies.

While each school under the NCAA is not technically required to follow the guidelines outlined above, any school that violates them would forfeit postseason play.

Understanding the Science Behind NCAA Policy

In the NCAA transgender student-athlete policy, testosterone is the holy grail.

“Prior to puberty, if you measure the levels [of testosterone] on little boys and little girls they are virtually the same, and there is really no difference in terms of strength, agility, capability and quickness,” said Fred Reifsteck, lead physician for the University of Georgia Athletic Department. “After puberty is when the male’s testosterone increases naturally, and that is where you can see the differences in the ability to gain muscle mass and strength.”

Women can gain muscle, agility and speed, but the average woman will not reach the strength gain and muscle mass that males acquire due to testosterone.

The argument behind the basis of the NCAA transgender policy is that suppressing a male’s testosterone would negate any strength and muscular advantage that testosterone may have provided in the cases of a male-to-female transition, once the transition is complete. In essence, if a transgender female’s testosterone levels are suppressed low enough, she can be on an equal playing field with cisgender females.

New Findings Raise Concerns on Policy

However, in a study published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, male subjects did not lose significant muscle mass or power when their testosterone levels were suppressed to the levels of IOC guidelines, which is the same as the NCAA. The study found that biological males could rejuvenate whatever muscle mass they may lose through proper training.

That study raised the question of whether or not the current NCAA policy is an adequate guideline.

“Unless we are going to go to a place where we decide to do away with sex as a category of participation, we have to have some way to decide who competes where,” Griffin said.

For now, the NCAA has decided that the way they decide who will compete where will be through testosterone levels. However, as the policy stands now, it doesn’t address where non-binary athletes, who do not identify with any gender, will compete.

“It is an imperfect system, but as long as we believe that having separate categories of participation for men and women is a good thing, and I do believe it is, we have to have some way to figure out where non-binary people play,” Griffin said.

Currently, the NCAA is taking another look at its transgender policies.

“At the time when the current policy was written, the committee didn’t have a lot of research on the topic of transgender athletes participating, and one of the things we always knew was as we gained more information, the guidelines would probably have to change,” Griffin said.

NCAA Policy at University of Georgia

Here in Athens, the University of Georgia’s Athletic Department has yet to adopt specific transgender policies because they have not had a transgender athlete.

“There are four things that I do think are important for our athletic departments to think about,” said Darrice Griffin, deputy director of administration in athletics at the University of Georgia.

How can we be proactive, how can we focus on inclusion, how can we protect the privacy of all our students, and how can we educate our students and our staff regarding the ways in which we identify?”

While she hasn’t yet tackled the subject of transgender athletes at the University of Georgia, Darrice Griffin came from the University of Massachusetts. While there, she aided in helping their athletic program adopt a transgender inclusive policy.

Occasionally, transgender athletes are going to win, like Telfer and Miller.

“The bottom line is we want sports to be a place where everybody gets to compete on a relatively level playing field, where the competition is fair,” said Pat Griffin. “The goal of the NCAA policy is to try and figure out how we do that so that transgender athletes can participate in college sports, but we also have to maintain the integrity and the standards in both mens and women’s sports.”

Katie Jackson is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)