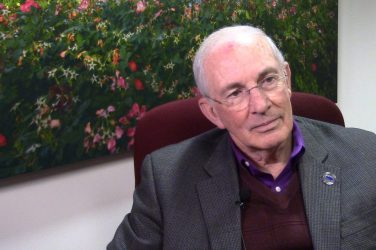

Greg Trevor, associate vice president for Marketing & Communications at the University of Georgia, worked for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in the World Trade Center in 2001.

“On the night of September 11, after we were evacuated, I got home very late in the night. I was talking to my father, and he asked me, ‘How should I describe you?’ He wanted to talk about my experience. He goes, “Are you an evacuee or are you a victim. I said, ‘Dad, I’m a survivor.’ My feeling is, anyone who experienced this, whether they were there, whether they were in New York City, or they watched it on TV, we were all survivors.”

“My office was on the 68th floor (of the World Trade Center), and that morning I was really stupid because I got to work early. I usually work the 10 to 6 shift, but that day I got in early.”

“I should point out that right before the plane hit, I looked up and it was a very bright sunny day. I could see the Statue of Liberty, glistening outside my window.”

“My estimate is that when the first plane hit, the building swayed 10 feet back and forth, you know like if you take a car antenna and swing in it. Yeah, that’s what it felt like. And then I looked out the window, and I saw a flame, like a parabola of flames come down through my window, and then there was this blizzard of paper and glass. And then nothing, silence except for car alarms on the street from all the vibration. And then, and then the phone started ringing, and it was media calling to find out what had happened. I spoke to someone from the local Fox affiliate, and he said, ‘Can you confirm that a plane hit your building?’ I said, ‘What is your source of information?’ He said, ‘About 200 people on their cell phones have witnessed it.'”

“The floor was starting to fill up with grainy smoke from the jet fuel, so we started throwing papers and folders and notebooks into a big bag.”

“There were two calls holding, so I told my colleague, ‘Okay you get rid of one, I’ll get rid of the other one, then we’ll get the hell out of here.’

I picked up the phone, ‘Greg Trevor here.’

‘Hi, I’m from NBC national news if you could just wait for five minutes, we’d like to put you on for a live interview.’

I said, ‘No I’m sorry. We’re evacuating the building.’

‘This will only take a minute.’

‘No, I’m sorry, we’re leaving. Yeah, you don’t understand, right now.’

He said, ‘But but but this is NBC national news.'”

“There was a whole bunch of people, you know, thousands of people in the stairwell, right, and it took about an hour to get down. And at first, you know, there wasn’t any real sense of concern for people, it’s like the building is on fire. We all need to go. We all know what to do. We would go down 2 at a time, and if an emergency rescue worker came running up, we’d all move over and let him or her through. That was fine until we got down to the fifth floor. It was 9:59.”

“I didn’t feel the impact of tower two being hit by the plane. We did know some of the stuff that was going on because one of my coworkers was at home that day having window treatments put in his house, so he was watching CNN and sending us messages. Phones weren’t really working though because everything was overloaded. So, we get down to the fifth floor, and the ground was rumbling, but we didn’t know what happened. That’s when the building started to collapse. I remember being thrown back toward the banister of the stairwell and hitting my back. Then I looked up, and all this smoke and dust fell into my face. Then, the lights died, and the stairwell filled up with smoke, and water started running down the stairs. I’ve described it feeling like I was wading through a dark, dirty river at night in the middle of forest fire. It was very hard to breathe. I had a cotton knit tie, I put it over my mouth and breathed through that.”

“Then I heard someone say, ‘Oh s***! The door’s blocked.’ What they meant was that the force of tower two collapsing had jammed the exit door at the bottom of the stairwell. Now here’s the procedure if you couldn’t get through a stairwell. You were supposed to cross through a hallway to get to the next stairwell and go down that one. Here’s the problem. At the fifth floor, there was no corridor. So, we were instructed to start walking up to cross. Now, I’m wading against the current of the river. We’ve got people coming down, we’ve got people going up. At that point, I wasn’t sure we were going to make it. That was the first time I felt a sense of panic on the part of other people. And what I did was, I said a quick prayer, I said, ‘Dear Lord, please let me see my family again.’ Then I closed my eyes and made a mental picture. I thought of my wife and our two sons. I made mental images of their faces in my head, and I thought to myself, ‘Their faces will keep me calm. If I die, they’ll be the last thing on my mind, this will be the last thing I will be thinking about is my family.'”

“We were very fortunate that the rescue workers were finally able to get the door unblocked, but now the question is, how do you get people to turn back around? Well, that’s when a gentleman who remains a friend of mine, David Lim, had the smart idea to start shouting ‘Down is good. Down is good.’ I heard that, and I shout it over my shoulder ‘Down is good.’ And you could hear it like an echo in the stairwell. And at that point we just bolted, it was like, let’s get at it. Yeah, we got out.”

I remember feeling like I was walking through a dirty snow globe that had just been shaken, that’s how much dust was in the air.”

“People are handing us water, TV crews are trying to interview us, we’re declining. Then all of a sudden, I feel this rumble behind me, and I look up and I see a New York City police officer say ‘Run for your lives,’ and I’m not trying to be funny here, but when police officers tells you to run for your life, you listen. So, we just started running. It felt like we were being chased by a cloud of smoke and dust. We ran for several blocks until we got near the Holland Tunnel. At that point I turned around and there was a gentleman named John Toth, that I knew who worked in the Aviation Department. He was limping, his pants were ripped, and he had a bloody knee. I said, ‘John, are you okay?’ He goes, ‘They’re gone, Greg.’ I first thought he was talking about a person, but no, not, not who, but the towers, and then I looked back. Because the towers were so tall and just dominated the skyline, that was one of the things I found myself looking at all the years I worked there. Whenever I was at a different facility, I always remember going and looking back to see where the towers were, it was kind of like looking where your work home was, so not having them there was incredibly unnerving. We were 700 feet in the sky, and where we worked didn’t even exist anymore. I called it the hole in the sky, that’s how it felt.”

“There’s a philosophy I try to follow. Every day is a gift. Every breath is a blessing. And I try to remember that even when we have difficult days, and you know there been some difficult days around the pandemic, but I always like to remember, this is an amazing world full of amazing people. There’s so much beauty, and there’s so much good that goes on, and I like to focus on that. I like to stay an optimist, and I like to stay focused on what is good about what is around us.”

Photo and interview by Ashley Galanti as part of the Advanced Photojournalism course at the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)