“I think parents can’t comprehend that kids as young as 9, 10, 11 could have eating disorders. They totally can,” says Robin Staub-Grundstein, a licensed dietitian and a certified pediatric and adolescent weight management specialist at Healthy Habits Nutrition Consulting in Athens.

Why It’s Newsworthy: According to new research released Feb. 25 from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, emergency room visits for eating disorders among 12- to 17-year-old girls have doubled during the coronavirus pandemic. When children are experiencing symptoms of eating disorders, there are many things parents can do to support their children and spot the signs of eating disorders.For Lynn Wilson, from Calgary, Alberta, symptoms of anorexia nervosa developed at the age of 10, as the bullying and teasing on the topic of her weight failed to cease — from girls on her bus to her grandmother at family functions.

“It’s not surprising I developed an eating disorder,” Lynn said as she reflected on it now at 16 years old. “Looking back, it’s disturbing thinking about the value that was put on my weight in elementary school.”

There are many ways in which parents and family members, especially, can prevent eating disorders in children from developing or becoming worse. For this year’s National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, the theme was “See the Change, Be the Change.” By seeing the change, especially as concerns for eating disorders among children have increased during the pandemic, family members can be the change by supporting children who may be experiencing symptoms of eating disorders.

See the change: Why eating disorders in children have seen an increase during the pandemic

“Just the increased stress in the world generally puts people at risk for mental health issues across the board, including eating disorders,” said Lauren Smolar, senior director of programs at the National Eating Disorders Association.

Concern about access to food also rose during the pandemic, Smolar noted. When people thought they were going to have to be in lockdown or quarantine, there was a concern about access to food. If someone is already struggling with their relationship with food, Smolar explained, and then doesn’t have access to a food they normally have regular access to — or on the reverse end, have an increase in access to foods they’re not comfortable eating — it can stress their relationship with food further.

In Northeast Georgia, among children specifically, disparities in access to food can be seen through food insecurity rates by county.

Flourish map / Kathryn Hunter

In addition to lack of access to food, however, there are several other factors in determining why children are at higher risk for eating disorders now than before the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, Staub-Grundstein said that her clients had been getting younger and younger. Now, during the pandemic, she says that trend has only continued – and possibly increased.

Children’s support systems have changed

One of the largest reasons for the increase in eating disorders during the pandemic for children, has been the change of surroundings in the lives of children.

“People’s community and support systems were changed often and continue to change. We know that there are people who either went back home or were not able to go home,” Smolar said.

Sometimes this meant children lost an in-person support system they had, but in other situations, this meant they were constantly surrounded by the very opposite of a support system, Smolar said.

“Sometimes, they were in closer quarters with less supportive opportunities. And there wasn’t really anywhere to go to escape that, which could make it a lot harder,” said Smolar.

“I think the pandemic definitely increased the time kids had to be alone — and be on social media and follow people who said, ‘this is what you should eat in a day,’ and get in their heads.” Staub-Grundstein said.

Social media has often been cited as playing a negative role in children’s lives when it comes to the pandemic and eating disorders.

“If their interaction was primarily on social media, there could be a lot of attention on image and appearance, and that can also put somebody at a higher risk for their relationship with food being negatively affected.” Smolar said.

Social media’s positive effects

But social media is not all bad, experts say. When analyzing your child’s social media activity, it’s important to analyze the intention of the media, says Smolar. When analyzing social media communities specifically, Smolar says it’s best to ask yourself what the intention behind any community is.

“Having some awareness yourself to make sure that the messaging and the environment you’re surrounding yourself with online is one that is safe and supportive and for recovery, that’s key,” Smolar says.

This awareness is especially important because of the amount of online spaces where recovery is not the main focus and rather, people are encouraged in negative and self-harming behaviors. For someone who is experiencing symptoms of an eating disorder, it’s crucial to be able to set boundaries for yourself online. When talking about harmful content on social media, Lynn says it’s been highly important to her to set a personal boundary, specifically against negative and unsafe communities online.

“I never sought out anything like that. I felt like that would make me just absolutely spiral, so I’ve never actively looked at something like that. I just know that’s a personal boundary that I wouldn’t let myself cross,” Lynn said.

Smolar also noted that when used in a supportive way, social media can be “a really powerful opportunity” for connection and community. “Navigating an eating disorder can be a nightmare — a seemingly isolating experience,” Smolar said. “If you don’t know of anyone near you who’s actively struggling, the internet is a really powerful opportunity.”

Social media can be a safe space and a supportive community, Smolar said, “if somebody can be really intentional about how they’re surrounding themselves with messaging, and curating a safe space for themselves.”

Lynn is in one of these “safe space” communities, a Discord server called “ED Support.” She joined the server of just over one thousand users last month to have conversations with people who felt like her.

“I know that people there have struggled with the same thing… it won’t be just the ‘oh yikes,’ or ‘lol same,’ that, you know, people around me may respond with. I feel like I can have a genuine conversation with someone that understands how I might feel,” she said.

Weight-related teasing can be detrimental to children

As a 10-year-old girl, Lynn was experiencing bullying from her peers on the school bus – and her extended family.

“It was super horrid. I was still a child, and I had no idea that my body was wrong or disgusting in some way. And I had these people around me, constantly reminding me that something was wrong. I was a bigger kid, but your body grows,” Lynn said. “I don’t understand why it was so different. I was a child, I didn’t warrant this. I didn’t ask for it. It was super evil.”

It’s completely normal for a child’s body to change and grow, Staub-Grundstein confirms. “There’s this whole awkward phase that’s just completely normal, when their body’s trying to catch up and do normal growth. Kids kind of see their body changing, and they panic,” she said.

But to Lynn, the bullying continued throughout elementary school. Once, she wore shorts to school because the weather was hot in the summer. A girl on the bus would bully her.

“She said that my thighs were massive. And I still can’t wear them because of it. Like that comment that she probably doesn’t even remember has stuck with me throughout my adolescence, like it’s insane,” Lynn said. “People don’t think that their words have weight when they’re so young, but like, I still think about it every day. She gets to, I don’t know, live her life. And I’m still like, controlled by her thoughts. It’s horrible.”

In addition, her own family would make negative comments about her weight. “What really, I think, progressed it into something more is that most of my extended family would use me as a punch line. And if my family believes it, and the people at school believe it, and my friends believe it, this must be my fault. Like, this must be a problem that I have to solve,” Lynn said.

“I just want to exist with my family, I don’t really want to be commented on if my pants look tighter. It’s just – it’s frustrating.”

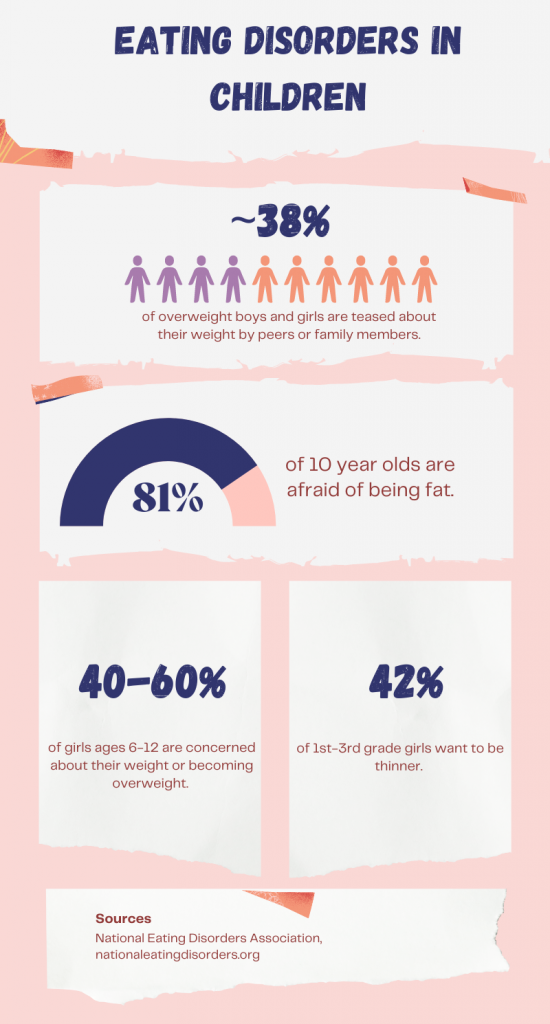

Experiencing weight teasing predicts weight gain, binge eating, and extreme weight measures, according to the National Eating Disorders Association.

In combination with the weight-related teasing, Lynn was put on medication for a vision-related condition that caused her to lose an unhealthy amount of weight in a short period of time. Combined with her onset of anorexia nervosa, in a single year she lost over 150 pounds.

“My doctors congratulated me. It was a victory for everyone else but me,” Lynn said. “It was the only thing I would think about for days, and I couldn’t sleep, so I had to stay up thinking about it.”

She began really tracking her weight, fine-tuning all of her focus to be on “whatever number was showing on the scale.”

“I’d feel rewarded if I was like, three pounds down. But if I had somehow gained a pound, I would cry about it for days on end.”

It became extremely exhausting.

She described dealing with the effects of delayed puberty because of her anorexia as well, such as delay in menstruation cycle, not growing any taller in her tall family, and experiencing hair loss.

“I had experienced extreme hair loss. I still have it now. I used to have really thick, wavy hair. And it’s like… the most heartbreaking part is like, people could look at me – but I started to not be able to look at myself,” she said.

Be the Change: How Parents Can Help Their Children

However, Lynn says, it was her parents who supported her and led her on a path to recovery. “I’m really close with my parents. When I would be so nauseous I could barely stand up, it was something they noticed,” she said. When her parents began to support her, she felt more comfortable.

“I felt like my best interest was their number one priority. My parents however have been supportive my entire life, they have loved me unconditionally, and for that, I owe them the world.”

Parents and family members should be aware of comments being made

Parents and family members should be aware of the comments that not only their children make such as self-deprecating comments, but also the comments parents and family members make related to food, Smolar says. “Most parents are genuinely trying their best. That being said, any additional attention on food can be really challenging for somebody who is already struggling or at risk of having an eating disorder. Focusing on numbers of any kind can be really challenging for somebody experiencing an eating disorder.”

Some things to avoid discussing, Smolar says, include but are not limited to calorie counts, the amount of nutrients in a food, amount of food consumed by the child, weight, and attributing positive or negative values to food.

In addition to comments by parents and family members themselves, it’s important to watch comments that children are making about themselves – especially when described in a self-deprecating manner, Staub-Grundstein says.

Before her parents began to have conversations with her about it, Lynn often made self-deprecating jokes as she was experiencing symptoms of anorexia.

“Nine times out of ten, [self-deprecating jokes] are their personal thoughts, and they’re just laughing about it to make themselves feel better. Because I’ve done that, and the people around me have done that. It’s just something to notice, because it can go unchecked for so long. If we don’t talk about it, it’s just going to get worse,” Lynn said.

Behaviors can set examples for children

In addition to eliminating comments in order to give kids positive body image, Staub-Grundstein says it’s important to not restrict food intake or diets in front of children as parents.

“A parent’s job is to set an example,” she said, explaining that she is also a parent with two kids. “I let them have cookies and candy and stuff like that, but I also have a ton of fresh fruit available and stuff like that.”

It’s important to not restrict certain foods for dietary reasons just because they may be unhealthy. If a parent doesn’t allow their child to have candy, Staub-Grundstein says, the kids are more likely to engage in binge eating behaviors.

“When my kids were little on Halloween, I always on the first night let them have as many pieces of candy as they wanted. And then they could have like, two pieces a night after that, after dinner or whatever. But I never threw it away, I never took stuff. And the candy would stay there till the next year, like they just lost interest. As opposed to, you know, friends who we’d have who would throw all the candy away after the first night, the kids would eat to the point of vomiting,” she said.

Lynn said that her parents talking with her about food and mental health in an open way was key to her recovery. “I felt more supported and I felt like I could breathe a little bit, with these changes towards food and eating, it made me feel less guilty,” she said.

“I had more say in the food that was bought, and we all changed our eating in a way that we could support each other. There was also less mention of weight in the house. No more scales. No more comments regarding the amount of food that was eaten in the house. No more, ‘Oh, did you eat that today?’”

Gaining education about eating disorders is key to understanding them

Staub-Grundstein says the most important thing parents can do is to educate themselves and be aware so that they can identify when there is a problem.

“Be willing to take your child for help and therapy, and do what you need to support their mental health,” she says. “When it’s kids with an eating disorder, you really have to educate the whole family.”

Smolar agreed, noting that it’s really important to try and get support from a professional who specializes in eating disorders.

“A great place to start is the National Eating Disorders Association helpline. We have trained volunteers, as well as a treatment database that has providers who do specialize in eating disorders treatment, across the spectrum of care — across the country, we have virtual options available as well, now more than ever,” Smolar said. There are also tips on how to start a discussion with a loved one about eating disorders on their website.

It’s especially important to talk to a professional because of how each individual child’s situation will differ, Smolar and Staub-Grundstein said.

Parents should become advocates for their children

However, parents’ support is still essential even after seeking professional help.

Staub-Grundstein said something that triggers her clients often is going to the doctor. “Every single time we go to the doctor for every single sniffle or whatever, they weigh you, and they put you on the scale. And for someone who’s dealing with eating issues, that’s triggering. I’ve had eating disorder patients tell the doctor or the nurse, and they still put them on the scale. And that will set them back tremendously,” she said, noting that this is especially important now when people go to the doctor for COVID-19 related appointments.

“Parents need to advocate for their children,” Staub-Grundstein said. “Being like, you know, ‘is a weight really necessary for this’, or you know, ‘my child’s struggling with weight issues, can we weigh them backwards?’ So I weigh all my patients backwards, whether they’re here for eating disorders or not. And I keep track, but they don’t see the weight in my office.”

The more we advocate for and raise awareness around education of eating disorders, Smolar said, the better the future will be for those at risk. “Eating disorders are serious. Recovery is possible. And you know, the more that we talk about it, the more barriers are going to be reduced and more opportunities for others to get the help that they need and deserve will be available,” she said.

Lynn agrees wholeheartedly. “We’re super vocal about mental health in my house. It’s not something we’re afraid to talk about,” she said. It’s important to her that they have conversations about how they feel.

One of Lynn’s major inspirations for her recovery has been her 5-year-old sister.

“I just love her so much, and the thought of her feeling the same way I did, or experiencing the same things I have experienced just hurt me so much, because she deserves so much better,” she said. “My adolescence has completely been about the way that other people see me, and I just want my sister to know that really doesn’t matter.”

“She’s just free to be who she is. She’s not worried about the way she looks. She doesn’t think about what she eats. So I hope that when she’s older, she feels like she’s safe enough to come talk about this kind of stuff with us. And I just wanted to make it so that in case she was bullied, the way that I was, she wouldn’t feel scared, and she would feel empowered enough to go to us or a teacher or someone she trusted for help. And not just let it sit, because I let it sit – and it didn’t work out.”

Kathryn Hunter is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (3)

Judi Slot Terpercaya

Thanks for every other informative site. The place else may just I get that kind of information written in such an ideal means? I have a venture that I’m just now operating on, and I have been on the look out for such information.

Robert Charles

Treatment for eating disorders includes a team of medical and mental health professionals. As unhealthy eating behaviors increased during the pandemic, care teams across Kaiser Permanente reacted quickly, offering virtual help.