GPT-3, the groundbreaking artificial intelligence language model, puts out more than just human-like responses to your questions — it’s estimated to release the same amount of carbon it would take to travel around the equator roughly 18 times in an EU-registered car, according to research from 2022.

Raghavendra Selvan and Daniel Hershcovich are two assistant professors at the University of Copenhagen tackling this sustainability issue by teaching a climate-friendly AI course, which is being offered for the first time this summer to doctoral students.

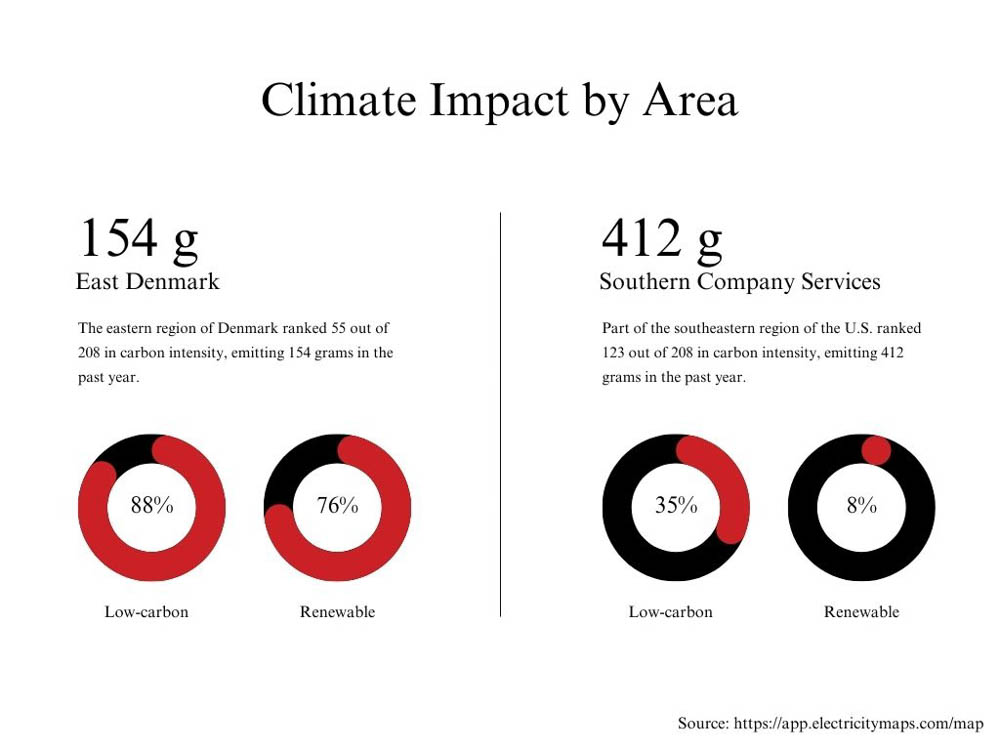

Why It’s Newsworthy: Eastern Denmark, where Copenhagen is located, ranked higher in carbon intensity of electricity consumed than the southeastern region where Athens, Georgia, is located, meaning they functioned more sustainably. The University of Copenhagen offers a Climate-AI course to address this AI carbon impact.

Climate-Friendly AI

It’s not immediately obvious how AI contributes to the carbon crisis with its high emissions. Most computers running AI programs use electricity that may not be carbon-free, and running the program itself also requires energy to cool the computers down. Carbon energy is also required to create the hardware used for the computers.

These are the foundational problems for this Climate-AI course. It’s aimed to make practitioners aware of the carbon impact, equip them with the tools to document it and provide solutions to make their AI use more energy efficient, according to the course objectives.

Selvan and Hershcovich also said AI can solve sustainability issues like the climate crisis. Selvan has worked with climate scientists on many projects to build models that better predict local ecosystem changes in response to the changing climate, such as counting insects and tracking the migratory behavior of arctic narwhals.

“[AI] will play a very important role because going forward, I think data-driven models will be important in handling, managing the climate crisis,” Selvan said.

He also noted other projects using AI to tackle sustainability issues that are still in the research process. Fritz Henglein, a professor in the Department of Computer Science at UCPH, utilizes blockchain, which is a shared database or ledger to track a product’s lifestyle, answering whether every step of the manufacturing process was sustainable.

There are many possibilities with predictive modeling that Selvan is excited about, like the potential interaction with Denmark’s windmills. Approximately 43.6% of Denmark’s electricity consumption was provided by wind power in 2021. Still, using some coal is necessary to fulfill the country’s energy needs.

Denmark struggled to provide enough energy through windmills in previous years, Selvan said. So, he thinks AI-based optimization could be implemented to balance energy production, maximizing the use of renewables and reducing the use of coal.

Sustainability Was Once New, Too

Denmark’s push for sustainable living only became a major focus about 15 years ago, Dane Niels Andersen said. Andersen did not grow up in Copenhagen but has lived there for the past 30 years.

He attributes the acceleration of new practices to the younger Danish generation. He’s witnessed the ongoing progression and has since adapted to the evolutions, such as the expansion of biking lanes and recycling categories.

There are currently 11 waste categories, according to the City of Copenhagen website. Denmark also made the world’s first law on recycling in 1978, saying “at least 50% of all paper and beverage packaging should be recycled,” according to the Waste and Resource Network Denmark.

Andersen acknowledges the number of categories will only continue to increase and biking lanes will only expand. Similarly, he observes the increased usage of AI in daily life, saying that it’s presence is inevitable.

“AI is something new and we have to as human beings be able, increasingly so, to be able to embrace new things that come our way and see how we can use it to our advantage,” he said.

He believes the societal sense of community made this sustainable movement possible in Denmark, compared to individualism in the United States. Starting small in local communities and recognizing individual benefits in the long run, which may be decades later, is how he says these changes can be implemented in an individualistic society.

Starting Small

Integrating these practices that use artificial intelligence and sustainability into U.S. society will not look the same as in Denmark, Heather Lent, a postdoc researcher at Aalborg University in Copenhagen, said.

Lent grew up in Tucson, Arizona, but has lived in Denmark for the past four and a half years. She currently works in low-resource natural language processing, which means there’s a lack of sufficient data to build NLP applications.

She sees an opportunity for AI to be more involved with sustainable practices and to be more sustainable itself, but is still not convinced of how successful this movement will be until more American lawmakers listen to AI researchers.

“The solution is policy turned into laws that is informed by actual AI researchers who know about the risks and what are actually problems,” she said.

However, there is a gap between the communities researching AI and those in industry, which Lent thinks might stand in the way of laws being implemented. Larger corporations have more access to resources than researchers typically do, which means their carbon footprint might also be larger.

Additionally, industry AI is interconnected with business models.

The narrative is coming from business people in big companies, not actual researchers. You know, that is maddening to me,” Lent said.

Hershcovich also warned about market incentives. He said we have to be careful that we don’t end up in a situation where AI is not aligned with human values such as sustainability, which might receive lower priority in efforts to maximize profit.

“I’m not talking about the dystopia where the robots take over but [a situation] where it kind of perpetuates existing biases and then doesn’t give people an opportunity to innovate,” Hershcovich said. “We need to really be clear about what’s important to promote in terms of value like sustainability and make sure that is inherent in the systems we use and deploy.”

Environmental sustainability of AI is important, but Selvan also thinks people need to consider the social and economic sustainability too. He recognizes that people might get displaced, requiring plans of action to retrain people into the workforce. He said researchers need to argue for reasonable regulations and laws because technology is growing at a “breakneck” pace.

Lent said as soon as you’re too proud, you stop innovating. A couple of solutions Lent offered were adding a carbon tax or requiring researchers to add a statement about the sustainability of their work alongside their ethics statement. But she also believes it is more nuanced than that, and the U.S. needs to go on its own path.

The work that people like Selvan and Hershcovich pioneer with AI and sustainability could ultimately be what helps other countries follow suit. Selvan said he cares about improving the efficiency of these models so that they can become smaller and more accessible to anybody, including researchers from other regions who can then solve their problems where they are.

Selvan said there are certainly some costs that we should start paying attention to, but AI is also a tool that can make very meaningful contributions.

Libby Hobbs is a junior majoring in journalism.

Show Comments (0)