In 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught on fire.

Floating pieces of oil-slicked debris were ignited by a passing train, sending the river in Northeast Ohio up in flames. The fire reached over five stories tall and lasted almost 30 minutes. It caused $50,000 in damages.

The river has caught fire 13 times, the first in 1868. The 1912 fire killed five people and the 1952 fire caused over $1.3 million in damages. Despite all that, it took the United States until the 1969 fire, 101 years from the very first, to finally become environmentally aware.

Jason Perry, program coordinator at the University of Georgia Office of Sustainability, said it was environmental disasters, like the Cuyahoga River catching on fire, that sparked the modern environmental movement.

Perry grew up during the 1970s energy crisis, a period when oil prices jumped up by 350% because of the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) oil embargo. It was growing up during that time period that instilled in him the knowledge that the environment can’t take care of itself.

“In a way I was indoctrinated by the media,” Perry said, noting a Schoolhouse Rock episode he remembers with a singing globe that encouraged children to use less energy because it causes pollution. “So I think that’s partly where my [interest in the environment] started. I also grew up [in the Adirondacks], a part of the world where there was a lot of natural beauty and I was taught to protect it.”

The people around Perry, however, were less driven by passion and more driven by costs. He recalls when the cost of throwing trash away increased and his parents purchased a trash compactor, as it was a pay-per-bag system. The price of gas rose, too, and his family went from a big station wagon to a Volkswagen Beetle.

In the 1970s, the modern environmental movement began picking up speed, encouraging people to care for reasons other than rising costs, with the first national Earth Day and President Nixon’s work with Congress to establish the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Now, 40 years later, the public has become more and more aware of how its actions impact the environment. More people are interested in taking steps to better the environment than ever before. Places like college campuses are a great place to look for examples of the modern environmental movement causing change.

Environmental Efforts on UGA’s Campus

The University of Georgia, among hundreds of other colleges, takes great efforts to make campus sustainable. In 2010, UGA established the Office of Sustainability.

Their mission is to “coordinate, communicate and advance sustainability initiatives at UGA in the areas of teaching, research, service & outreach, student engagement and campus operations.” They do so by promoting a number of operations, including advancing sustainability in campus athletics, dining, and transportation.

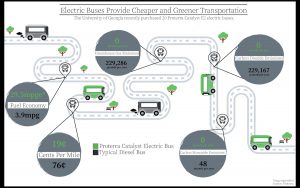

There are six transportation initiatives alone, including a recent purchase of a fleet of electric transit buses. The buses will reduce toxic gas emissions from transit buses on campus to zero.

Kimberly Arriaga, a fourth-year environmental engineering major from Tucker, Georgia, rides campus buses every week day. “I think [the purchase of the electric buses] is a step in the right direction,” Arriaga said.

Other transportation initiatives include a bike share program, free for use by UGA students and employees, and a second bike program called UGA recycle that refurbishes abandoned bikes on campus for students or employees who need transportation.

For those who drive electric vehicles, UGA has installed ChargePoint electric vehicle chargers in multiple parking decks around campus. In addition to the parking deck hourly rates, EV drivers will have to pay $0.75 for the first two hours and $1.50 for each additional hour.

These initiatives, however, are only useful if students are aware of them and understand how they work. Nick Hummel, a fourth year English major from New York, said “if [UGA] did promote it more, it’d be better received.”

Student’s individual actions, in addition to university wide initiatives, have an effect on campus, too. Unfortunately, their effect is not always positive.

Hummel took notice of confetti littering a field on campus from a graduation photo shoot and posted on a student led Facebook page explaining his disappointment. A photographer himself, Hummel explains to his clients the impacts of the confetti on the environment and suggests alternatives, like flower petals or holes punched from leaves.

For reasons like abandoned confetti, Hummel also notes that the university’s efforts are incredibly essential to teach people, students on campus and people nationwide, why choosing sustainability is important.

“I think a lot of the problem with people’s awareness and blatant ignorance is they don’t really know. They’re like ‘oh well I’m just one in a million so me not doing this one thing or doing this one thing but leaving it for someone else to deal with isn’t as big a deal,’” Hummel said. “I think awareness and promotion of that to help people understand that even one person changing things does make a difference.”

In agreement with Hummel, Perry said understanding the environment and sustainability is important. He also believes surrounding students with as many sustainable advances as possible now will impact their future.

The importance lies in “creating an environment where young people see that these things are possibilities. And not just possibilities, they’re realities,” said Perry. “It’s showing them that this is a possible future for wherever they choose to live after college.”

Like Perry, Arriaga said environmental disasters, specifically Love Canal in Niagara Falls, NY, “opened some American’s eyes to the adverse effects human populations are having on our environment.”

She hopes that people will continue to realize that “we are using our resources without recycling or replenishing them. In a few decades, there won’t be any more coal or natural gas because we have consumed it all.”

Moving Forward

Despite new efforts within the last 40 years to improve environmentally damaging habits, the future is still uncertain. If we don’t stop polluting, according to the Renewable Resources Coalition, our air will become foggy and our oxygen harder to breathe. All types of life, including humans, will become extinct.

It’s hard not to think that there’s going to be a lot of regret for not taking more action,” said Perry. “We don’t really know what the ultimate effects of the things that we’ve been causing for the last 100 years are going to be.”

Kalah Mingo, a recent UGA graduate from Lagrange, Georgia who also posted on Facebook about confetti littering campus, said, “Hopefully, more people will be environmentally conscious and willing to do their part to preserve what we still can.”

One solution could be implementing more drastic efforts, like required recycling or banning single use plastics. Both Arriaga and Perry mentioned a charge for plastic grocery bags, which would simply encourage people to bring their own reusable bag.

Many states, however, have already tried to ban single use plastics with a great amount of backlash. Mingo offers an alternative, suggesting a shift of focus to large companies. “I feel like focusing more on large companies that cause the majority of environmental damage would be more effective,” Mingo said.

In the case of the Cuyahoga River, keeping large industries from dumping waste into the river was a good start. One of the first legislations the EPA implemented was the Clean Water Act, which mandated that all rivers throughout the U.S. be hygienic enough to safely allow mass amounts of swimmers and fish within the water by 1983.

Arriaga believes for real change to happen the population needs to be informed at the educational level. “Instilling the reality of resource depletion, oil spills, filling rates of landfills, etc. would aid in developing a more realistic and conscious population,” Arriaga said.

However the change happens, the fire has been lit under the population rather than on top of rivers. Perry said, “I see a lot of hope, but also a lot of anger and the momentum is encouraging.”

Emily Lanoue is a junior at the University of Georgia pursuing a bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in communication studies and a certificate in new media.