According to Athens-Clarke County senior planner Bruce Lonnee, an incongruously sized house can literally and figuratively throw shade on its neighbors.

In in-town Athens neighborhoods like Boulevard or Five Points, streets full of smaller, older cottages are often juxtaposed with newer, larger houses.

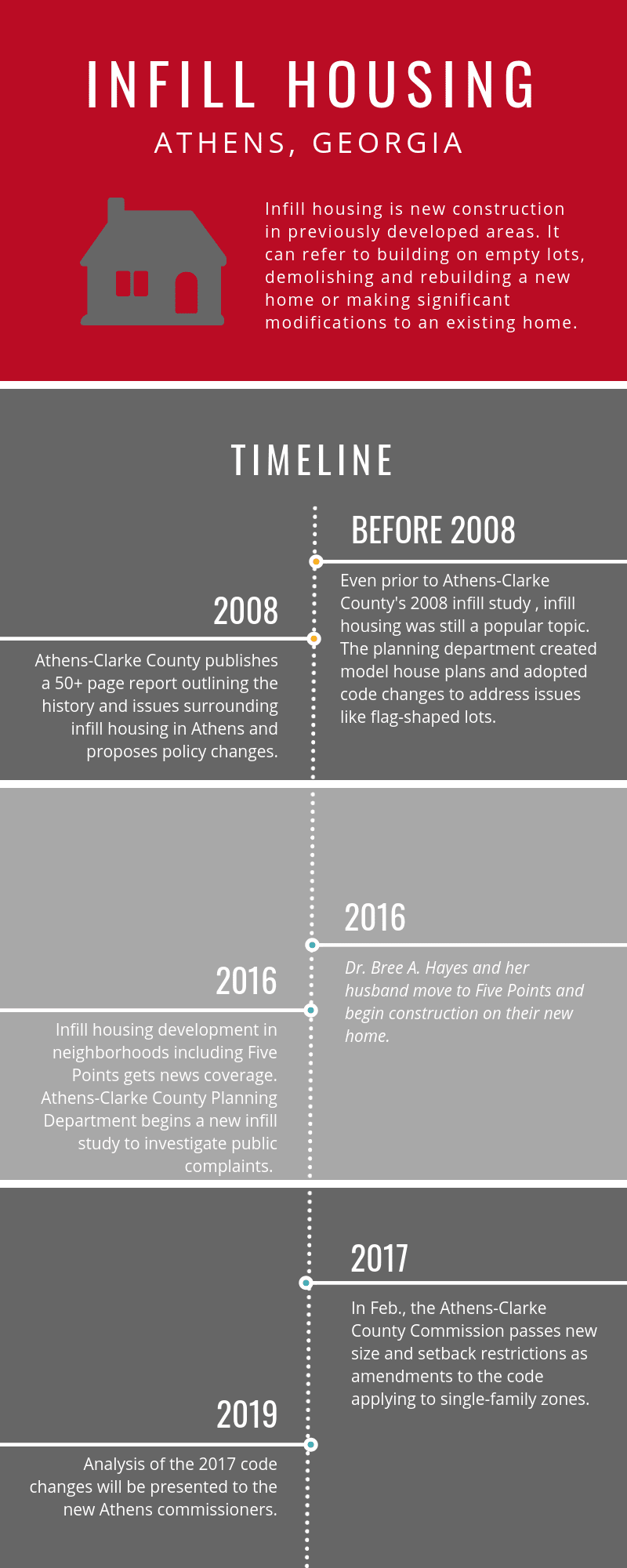

The new homes are examples of infill housing, or new construction in previously developed areas. This can take the form of building on an empty lot, demolishing one home and building another or building significantly onto an existing home.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Infill housing development can impact the infrastructure, character and property values of a neighborhood. In February 2017, Athens-Clarke County made changes to local code to address infill issues related to home size in single-family zones, but the analysis of their effectiveness is ongoing.

Athens-Clarke County Commissioner Melissa Link, District 3, said filling in these empty spaces can be a good thing.

“As we grow as a community, it’s important to accommodate people in existing neighborhoods where there’s already infrastructure, especially existing in-town neighborhoods, where people are close to jobs, services, transit and all that,” Link said.

Despite this purpose, infill housing has generated plenty of criticism in recent years. In response to these issues, the ACC planning department took on its third infill study in the last two decades, most recently in 2008. Ultimately, this study resulted in changes that were passed in February 2017.

But what it did not pass was an infill housing ordinance.

Lonnee pointed out the common misunderstanding of this issue. What passed in 2017 was a series of amendments to existing code to address infill issues, not a separate ordinance.

“Planner guy pet peeve,” Lonnee said.

These amendments dealt largely with size in response to infill construction that was out of scale from the surrounding neighborhoods, and they only impact single-family zones.

Lonnee and the planning department is still working on the analysis to determine the impact of the 2017 changes. He said they plan to report to the new commission when they are sworn in in January.

“Is the end result in the field actually solving the problem?” asked Lonnee.

But size is not the only problem related to infill housing.

Criticisms of Infill Housing

Lonnee groups the opposing arguments into a few main categories. First, some criticism is related to infrastructure.

“You know, the streets aren’t enough to carry the additional traffic, or the water or the sewer is not sufficient to support the additional units,” Lonnee said. Or, in more widespread instances of infill, the school districts may not be big enough to take in the new residents.

Next, although Lonnee doesn’t like to point to architectural style as the most important criticism of infill, taste is a major part of the public’s perception of the problem.

“One person’s post-modern dream is another person’s nightmare. And when you have a neighborhood with a bunch of little cottages and somebody builds something that’s a postmodern box, it could be extremely elegant and expensive to design, but it just sticks out like a sore thumb,” Lonnee said.

When Bree A. Hayes and her husband built their new home in Five Points two years ago, they tried to be mindful of this. Throughout the design process, they knew they wanted their new home to fit into the surrounding neighborhood.

“We built it to look like it was once a little house and people kept building onto it,” Hayes said of their Milledge Circle home. The original little house, though, was demolished due to faulty wiring, a bad roof and asbestos.

“It broke our hearts,” she said.

To preserve pieces of the former cottage, the couple repurposed a light fixture and part of the old attic. They also transplanted trees that otherwise would have been clear cut during the construction. And with time, the stucco walls will grow green and help the house to blend in.

But regardless of its ability to fit in through design, the house stands three or four times bigger than the 1930s cottage that once stood in its place.

Hayes said she received no pushback from her neighbors during construction, but this is not always the case.

Size is another main complaint against infill housing.

Longtime Five Points resident and retiree Sue Stephenson is unhappy with this recent development of “megahouses.”

“I think they’re destroying the character of Five Points,” Stephenson said, noting that the large lots, trees and flowers she enjoys often disappear with new construction. Having lived in Five Points since 1967, Stephenson has noticed more infill development in the past decade.

The final criticism against infill housing is its impact on property values. One complaint is that in affluent areas, poorly-executed infill can drive property values down.

But when infill houses are nicer than the surrounding homes, property values increase—and so do taxes. This becomes a bigger problem in socioeconomically depressed areas.

“You may start to see a trend where people are getting priced out of their homes…Infill can sometimes lead to displacement of existing owners, gentrification, that whole sort of dynamic,” Lonnee said.

Link pointed out that this has been a big issue for people living in historically African-American communities like the West Hancock Avenue Corridor, a neighborhood which is zoned as multi-family and therefore is not aided by the 2017 code changes.

“What’s really rough on these folks is their property values go up so much, and they can’t afford their taxes,” Link said. “A lot of these folks are living in houses that their grandparents built 100 years ago, and their only housing expense is their taxes.”

Moving Forward

Although the 2017 ordinance changes do not address all of these issues or areas, Lonnee said the study was meant to address the biggest concerns in the community, which did not include multi-family zones.

The planning department is still measuring the outcomes of the changes, but Lonnee said they have yet to record a single violation of the updated code.

“So that’s a good sign,” he said.

But the county has yet to determine the community’s response.

“It’s too early to tell if it worked,” Link said.

Kendall Lake is a fourth year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Georgia.