With Georgia placing among the top four states with the highest rates of incarceration, one advocate for criminal justice reform is using his personal experience to help other formerly incarcerated individuals reintegrate into their communities.

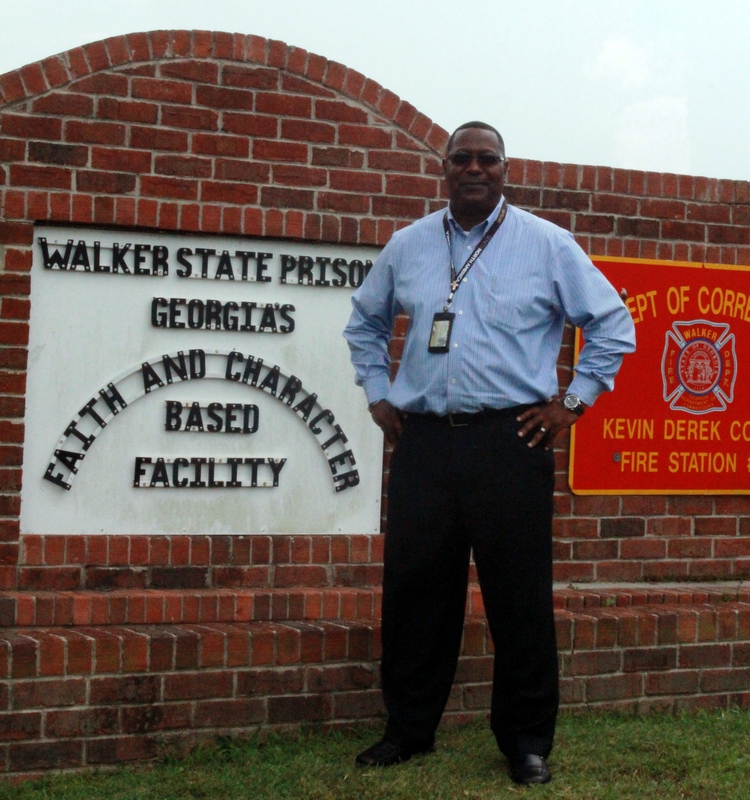

For Tony Kitchens, Georgia Center for Opportunity’s (GCO) Field Director of Prison Fellowship and board member, reentering society after his incarceration was not a smooth transition.

“My greatest challenge was not doing the 11 years in prison, it was living as a marginalized citizen for over 29 years as a result of these tough-on-crime policies,” Kitchens said.

In 1974, Kitchens was incarcerated for a relatively minor offense. Kitchens said that in the 1970s, the criminal justice system “was all about punishment, it was all about lock them up and throw away the key.” At the time, reform efforts were not even a consideration and reentry services were virtually nonexistent.

Now, he is dedicated to changing this issue in Georgia.

Why It’s Newsworthy: With a prison population of over 47,000 individuals, Georgia is the fourth-most incarcerated state in the nation. Advocates for criminal justice reform say connecting formerly incarcerated individuals with employment opportunities is the best way to lower this number and decrease recidivism.

The reentry process occurs when a formerly incarcerated individual rejoins society. However, Kitchens believes this reentry standard, which often serves as a benchmark for recidivism data, needs to be reevaluated.

“You can simply be successful with reentry by living under a bridge — reentry has very little to do with your quality of life, so that’s why it’s important to expand the conversation to begin to include community reintegration,” Kitchens said.

Georgia Center for Opportunity

Georgia Center for Opportunity (GCO), a nonpartisan policy research and solution delivery organization, uses its resources to support both reentry and community reintegration efforts across the state.

Kitchens started working with GCO in 2013 when Chief Program Officer and General Counsel Eric Cochling put together a Prisoner Reentry Working Group. Cochling was gathering various stakeholders in the community, and Kitchens asked him, “’Do you have anybody on that panel who’d actually been to prison?’ and he said no and asked me if I’d like to be a part of it,” said Kitchens.

With the help of a policy recommendation made by GCO, Kitchens became one of the first formerly incarcerated individuals to work with the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support, and Reentry in 2015 under former Gov. Nathan Deal.

GCO partners with businesses and nonprofit organizations to bring employment opportunities to underserved communities. Cochling, who helps manage the organization’s outreach, said that GCO requires its partners to be open to working with people with criminal histories, and he has personally observed changing attitudes toward reform.

“On the business side within our recruiting, there’s far more willingness to work with the population than there was 10 years ago,” said Cochling.

GCO is mostly funded by individual contributions and private foundations, and Cochling said the organization intentionally avoids direct grants from the government in order to maintain its independence. When describing political rhetoric on crime, Cochling said, “we don’t seem to modulate very well between the two extremes, and I think that has to do with us being slow to respond, and, by the time we respond, we overreact.”

Political Perspectives on Criminal Justice System

In Athens, Georgia, state Reps. Houston Gaines (R-HD 117) and Spencer Frye (D-HD 118) both agree that access to employment is the best way to combat recidivism. The representatives also stated that they believe the criminal justice system is in need of reform but have highlighted different ways to evaluate this issue.

In this last election, I went door to door, and when I talked to voters, there were two issues that were top of mind: inflation and public safety,” said Gaines.

Gaines said his biggest concern with the local criminal justice system surrounds prosecutorial discretion and believes “its incentivizing criminal activity.”

“We have a situation right now in Athens where we have a district attorney who’s choosing not to prosecute certain classes of crimes and that’s not the job of the district attorney. The job of a district attorney is to enforce the law that the general assembly writes,” Gaines said.

For Frye, private prisons and “bias” within the criminal justice system are his biggest concerns, and he would like to see the criminal justice system shift its focus from a punitive process to a more rehabilitative approach.

“I think the whole concept around the political rhetoric based on crime is not rhetoric rooted in fiscally sound judgment, it’s rhetoric rooted in motivational fear,” Fyre said.

Contextualizing Political Rhetoric on Crime

“In all of these reform areas, both the conservatives and the liberals have a real problem with just focusing so much on anecdotal things as driving a lot of their decision making,” said John Meixner, assistant professor at the University of Georgia’s School of Law.

Before entering academia, Meixner served as a federal prosecutor for almost six years and said his role did not radically change when different political parties were in control. Meixner believes the goal should be to incarcerate “the absolute minimum that we think is necessary to achieve the ends of justice.”

“There are many opportunities where a non-incarceration option can serve those same ends of justice, and, in a lot of ways, be much more cost effective,” said Meixner. It is important to take a broader look at data, not anecdotal evidence, when making decisions about criminal justice reform according to Meixner.

The Path Forward

Nonpartisan organizations like GCO remain a vital part of both prisoner reentry and community reintegration. GCO’s outreach creates a link between the organization’s policy goals and the individuals who need it.

“You can build the $50 million policy yacht, but if you don’t build the $5,000 bridge, it has zero value for those who can’t get on it,” said Kitchens.

Turning his experience within the criminal justice system into a platform for advocacy helped Kitchens become a champion for change by communicating with and empowering others.

“When you’re talking with people who are going through a marginalized experience, the ability to ask questions as opposed to just telling them the answers not only helps that person embrace their dignity, but it also helps them to find a solution to the problem themselves,” said Kitchens.

Jenna Monnin is a senior majoring in journalism and political science.

Show Comments (2)