When the clear feeder creek behind John Lee Thomson’s home and the fish hatchery he works at turned muddy after a quick rain, he knew there was a problem.

Thomson started to hike upstream to find a clear-cut lot missing all of its trees. Red mud spilled into the once-clear creek.

What Thomson saw behind his home is one example of a larger problem affecting trout streams across North Georgia: sedimentation. When development clears trees near streams, improper practices can lead to erosion. Erosion can cover the gravel creek beds Georgia’s trout rely on to spawn, putting the species’ survival at risk.

“If it can happen right next to the fish hatchery, think about where it’s happening all over North Georgia,” said Thomson.

However, Thompson said sedimentation is not the only threat to this fish species.

Thomson is the trout stocking coordinator for the state of Georgia, and began working for the Lake Burton Fish Hatchery in 2006.

Three trout species exist in Georgia: brook trout, brown trout and rainbow trout. Brook trout are the only trout native to Georgia, while rainbow and brown trout were introduced into streams in the 1880s.

According to the Georgia DNR, trout require continuously flowing and well oxygenated water to survive. Trout cannot live in water temperatures greater than 72 degrees Fahrenheit, but young trout have much greater biomass in temperatures below 67 degrees.

In a study conducted by the University of Georgia in 2020, researchers predicted that an average water temperature increase by 1 to 2.6 degrees Celsius could decrease suitable trout habitats by about 25% to 67% respectively.

It does appear that streams are getting a little warmer, James Miles, Georgia’s Wild Trout Biologist, said.

Scientists and researchers are definitely seeing the effect of these issues within Georgia’s streams, Miles said.

“We’re getting a lot of these hundred year floods, and they’re happening almost every year now,” said Miles.

In the 1980s, Georgia experienced five events that were related to either drought, flooding, severe storms or cyclone events. In the last five years, Georgia has experienced 37 of these same events, with 14 in the year 2023 alone.

With flooding, Miles said, one of two things will happen. A flood will either completely wash trout eggs away or bury them through erosion and siltation.

We cannot do much about the flooding, Miles said, other than continuing to monitor the fish and attempt to restore a stream if it were depleted.

However, with drought, conservationists can try to give trout as much thermal refuge with woody debris, which is strategically placing brush in the water to create habitats, or maintaining riparian zones, said Miles.

According to the National Park Service, riparian zones are areas located along the edges of lakes, streams or rivers whose “soils and vegetation are shaped by the presence of water.” These zones provide habitat, maintain water quality and stabilize stream banks to minimize erosion, sedimentation and siltation.

Both Miles and Thomson said the biggest threat to wild trout in the state of Georgia was sedimentation, which is synonymous with habitat loss.

“If you can maintain that riparian zone, there’s a less likely possibility of silt and sand eroding into a creek, which destroys fish habitat as well,” Miles said.

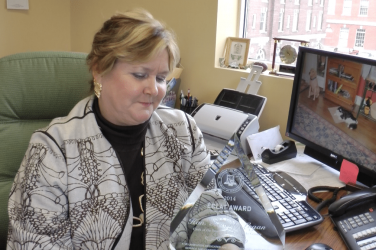

As sedimentation from actions like development and erosion potentially pressures trout habitats, conservation efforts like trout stocking and hatcheries become more critical, said Thomson. He works at one of three trout hatcheries operated by the Georgia DNR.

The Burton hatchery aims to stock 160 streams with about 1 million catchable trout each stocking season, Thomson said. It takes two years to get a fish up to a stockable size, which is where the hatchery comes into play.

According to Nicole Farnham, a fisheries biologist for the Tanana Chiefs Conference, some argue that fish hatcheries can reduce genetic diversity. With a lack of diversity, fish may be more susceptible to diseases and fail to adapt to a change in the environment.

The hatchery has two methods of cultivating trout: raceways and dual drain circulars. Raceways are long, narrow pools where larger trout live with the hope of having an unlimited flow of water, which can be difficult to maintain during droughts.

Dual drain circulars are large pools that are protected and biosecure. Many eggs and fingerlings, which are smaller trout, live in the enclosed shed of dual drain pools until they are big enough to move into the raceways.

Once the trout reach an appropriate size, Thomson and the hatchery begin stocking annually in March.

With the stocking season comes pleased anglers and trout conservationists alike, said Thomson.

“You’re basically driving a giant ice cream truck through the National Forest,” Thomson said. “I mean, people are so happy to see you when you come and stock fish.”

While trout stocking programs provide support to populations and excitement for anglers, the larger battle to protect these fish is ongoing.

“I think now there’s more awareness for protecting our fish species or native fishes, especially the brook trout, than ever before,” Miles said.

Bennett Ulm is a senior majoring in journalism.

Show Comments (1)