The Filthy Boy

You wake up in the middle of the night and a young, blonde, bushy-haired boy towers over your bed. His fingernails crookedly snake up the walls of your room and graze the ceiling. A smell like the inside of a dumpster hangs thick in the air, so much so that you find it hard to breathe. The boy smiles at you, revealing his rotting teeth, and tells you to take a bath every day.

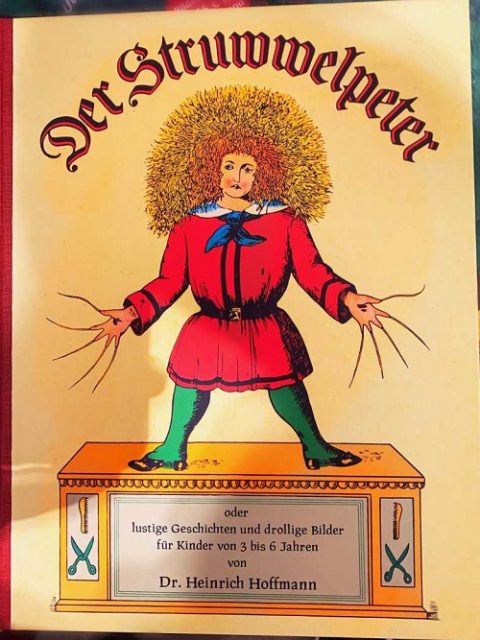

The tale of the bushy-haired boy with fingernails twice the length of his hands is a German bedtime story within a large book of German fairy tales known as “Der Struwwelpeter.” It sold 3,000 copies at its release in 1845 and more than 20,000 copies three years later in 1848. “Der Struwwelpeter” may be fearful to modern Germans today.

Michaela Gemkow, a blue-eyed blonde librarian with a toothy grin working in the Munich city library of the Rosenheiemerplatz of Munich Germany, elaborates on “Der Struwwelpeter.” “For modern librarians and modern teachers, it’s really scary. I don’t want any child to see this.” But before World War II, it was a staple bedtime story for children ages 6 to 10.

Gemkow notes that books began to see a shift in character around the ’60s after World War II. Children books became “more modern.”

Why It’s Newsworthy: Children’s literature is a representation of the changes of German societal thinking patterns from pre-World War II to post-World War II. The changes in bedtime stories allow us to see the differences between past and present German society.

An Evolution

If you want to witness the changes within German society from before World War II to modern Germany today, “Der Struwwelpeter” represents the societal patterns of thinking before the war. Children books in Germany have evolved from tales of unwavering discipline to stories that focus less on discipline and more on building up one’s own self-esteem.

Gemkow mentions that, in fact, German librarians do not like this book [“Der Struwwelpeter”].

This is a very old-style pedagogic book. It’s very strong and serious and the adults are always right, and the children always have to do what they say. It’s about a 100-year-old book.”

“Der Struwwelpeter” was published in 1845 by the playwright and illustrator Heinrich Hoffmann.

The German Student Movement

“It was the revolution of 1968. The younger generation didn’t want to think the same way as their parents, because in their eyes the ways of their parents were the reason for national socialism. So, they wanted to make a cut there and this was the start of modern pedagogic literature, and the teachers in this time began to change their methods,” Gemkow remarks.

West Germany in the late 1960s experienced what is known as the “German Student movement.” The movement began because of unrest among German students who looked down upon the western German government who they viewed as national socialists after World War II. Along with wanting to acquire better living conditions, students also made a goal of embarking on new ideas of democracy as well as changing Germany’s school curriculum.

No More Bloody Thumbs

Besides the story of the bushy-blonde boy with dangerously long fingernails, “Der Struwwelpeter” also depicts the story of a boy who continuously sucks his thumb. The result is that a character known as “The great tall tailor” cuts his thumb off with scissors. The book features a detailed illustration of blood dripping down a hand as a child’s thumb falls to the floor.

Gemkow chuckles as she recalls that a few years ago her husband lost his thumb in a work accident. One of Gemkow’s family members read the story about the boy whose thumb was cut off to Gemkow’s daughter. As she told the story of her daughter’s first exposure to “Der Struwwelpeter,” she widened her eyes horrified and said,

My husband said to my daughter look, it’s real, it happens.”

She discloses, however, that today her younger children do not look at old traditional books but prefer Disney princess movies.

A New Attitude

Gemkow says that more modern German children books are now available in German libraries such as princess and adventure books, a result of the change in literature after the “German Student Movement” in 1968.

She thinks that modern German children books bring upon an attitude of equality between children and adults. “I think the modern German children books want to see the children at the same level of the adults,” Gemkow claims, “So, there is a really democratic kind of telling of stories and the pictures of the children has really improved in the last 50 years.

We all laugh now at Struwwelpeter.”

Max and Moritz

Petra Albrecht, a bookstore employee at the Hugendubel bookstore in the Marienplatz of Munich says, “There are some customers who ask for it [“Der Struwwelpeter”] but it’s not so popular anymore.”

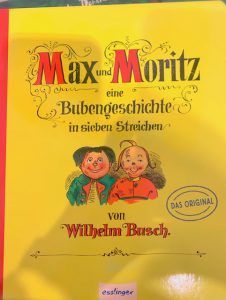

Another popular traditional book for children in Germany was “Max and Moritz,” a story about two mischievous boys who are constantly getting into trouble. Albrecht remarks with a flat tone that

a lot of the time they get away with it but in the end, they don’t… it doesn’t have a very happy ending.”

She flips to a picture within the book Max and Moritz of the two boys turned into bird food at the end of the book.

Today’s Stories

However, Albrecht states that they offer many kid-friendly books in the bookstore. The only people that really come in to buy the more traditional German fairy tales are of the older generation who know it from their own childhoods. Albrecht says. “I mean it’s like culture, it’s not so bad that the children know it.

I wouldn’t give it to my children as a first book because they would have bad dreams about it.”

You can still find “Der Struwwelpeter” in the children’s section of the Hugendubel bookstore, but today, German adults try to give children books that will improve their self-esteem and awareness of the world around them, as well as aid them in cultivating maturity.

The most important thing for European children books now is to have your own character,” says Gemkow. “[to] find your own way and don’t be sad if you are not the same as your neighbor.”