It was one of the most highly anticipated days for Georgia football in the 2019 season, but Colin Beecham wasn’t nervous. The morning and afternoon leading up to the game were filled with an appearance on ESPN’s College GameDay and later, time at the Dawg Walk. When he and the rest of the squad finally set foot on Dooley Field, he took his place alongside the rest of the spirit squad and helped the student section cheer on the Bulldogs to a 23-17 victory over Notre Dame.

Beecham, a senior real estate major from Milton, Georgia, is one of 13 men on the University of Georgia’s cheer squad and one of thousands of male cheerleaders across the country.

Male cheerleaders made up 21.5% of all cheerleading participants in 2018, according to a Sports & Fitness Industry Association report. A UCLA study reported that this percentage rises to 50% for collegiate teams.

Cheerleaders have remained an American icon since the sport’s beginning in the mid-1800s, according to Allison Wright’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Texas at Austin on the history of cheerleading in the U.S. While the sport began as an all-male activity, the gender balance began to shift following World War II and has since been regarded as a mainly female sport, Wright said.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Recent societal changes regarding gender and a better understanding of competitive cheer have changed society’s perception of the sport.

Close your eyes and imagine a cheerleader. What’s the first image that comes to mind?

Wright found the majority of cheerleaders from the 1950s to the present were white, middle-class, heterosexual and female. This image carried over to media and literary representations of cheerleaders as “a female who is small in stature yet feminine; adheres to westernized notions of beauty; has long, often blonde hair that manages not to interfere with her athleticism; and is physically fit but not grotesquely muscular.”

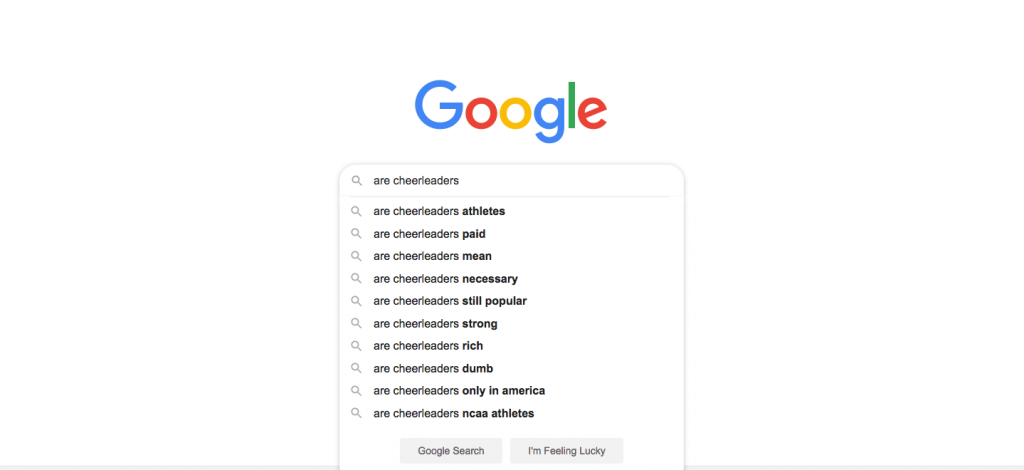

A Google search for “are cheerleaders” reflects commonly held stereotypes that cheerleaders don’t just look a certain way, but hold a certain hierarchical status.

“When people think of cheerleading, they think of pompoms, hairbows, stuff like that,” said Kaleb Comer, a member of UGA’s spirit squad and a junior health promotion major from Marietta, Georgia. “They don’t really see the athletic side of it, they only see the appearance side of it.”

Comer, who also coaches at Oconee Gymnastics & Cheer in Watkinsville, Georgia, said many of these stereotypes come from people only being exposed to sideline cheering at high school games.

However, sideline cheering can also be physically intense and a lot of work. Tracee Allen, the varsity basketball cheerleading coach at Cedar Shoals High School and a former cheerleader herself, said she wishes more people took the sport seriously.

“I would love to see support from, you know, higher ups taking cheerleading and seeing it as a sport, not just sideline,” Allen said. “I feel like we work just as hard and sometimes we don’t get the same respect as other sports at a high school.”

Tykerius “T.K.” Monford, a junior at Cedar Shoals and the only male cheerleader for both the football and basketball varsity squads, spoke to the amount of work the team puts into being prepared for each game

Along with memorizing over 100 cheers, Monford said the teams utilize a form of cheerleading called “stomp n’ shake.” This form originated in Virginia and the Carolinas by African-American students in the 1970s, according to an article published on the United Black Books website. Monford said “stomp n’ shake” integrates elements of stepping, as well as dynamic body positions, personality, attitude and sass.

Stepping onto the Field of History

While male cheerleaders may seem rare today, they made up entire cheer squads when cheerleading first began in the U.S. Take a look at the timeline below to see some of the sport’s important milestones.

In her book “Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture,” Mary Ellen Hanson provides a rich look at the history of American cheerleaders. By the 1970s, she writes that cheerleading was “prevalent in public schools at all socioeconomic levels and it was done primarily by females. Perceived as a feminine subsidiary to masculine athletics, cheering thus became trivialized.”

Ken Khamphiphone, the co-owner and operations manager of the Tumbling Academy of Cheer and Acro, began cheering 20 years ago in high school and said being a male cheerleader was much more taboo than it is now. One summer, he was one of only four boys at a cheer camp that included 500 athletes.

“I was ostracized for a good while, but that was because anyone looking outside of the circle didn’t see the kinship within,” Khamphiphone said.

Stereotypes in Cheerleading

While Comer said he hasn’t faced any discrimination or harassment as a male cheerleader, Christian Paniccia, a cheerleader for Young Harris College’s competition team, said some of his former high school coaches and teammates ignore him and make jokes about his sexuality when he decided to switch from being a football player to cheering them on from the sidelines.

“So that’s where I kind of learned like who’s my friend and who’s not. And who’s actually there to support me, and who’s just there to hate,” Paniccia said.

Many of Paniccia’s former teammates—and even his dad and brother—asked if he was gay when he decided to pursue cheerleading.

Society’s assumed correlation between femininity and gay males accounts for this stereotype, according to a 2006 study entitled “Cheerleading and the Gendered Politics of Sport.”

The same thing happened to Beecham when he made a post on Instagram about making it onto Georgia’s cheer team. Among encouraging comments and congratulatory messages, he also received a couple messages from some people from high school asking if he was gay.

Since being a male cheerleader was a much larger taboo when Khamphiphone was in high school, he recounted how at an away game, someone from the other team put out a cigarette on his fellow teammate.

“That was definitely a metaphor of like, how it was viewed,” Khamphiphone said. “It was very uncommon — it was like a target on our backs to get picked on.”

Nowadays, societal shifts toward inclusion, diversity and equity have begun to break down barriers and stereotypes in many areas of life, including athletics. In fact, the cheerleaders interviewed for this article said they haven’t faced any outright harassment or discrimination and are even respected.

Even at the high school level, where male cheerleaders are more rare, Allen said many people who attend the games know Monford by name and will ask about him if he isn’t there.

“As a sport, it’s no longer defined anymore as feminine or masculine. I think it’s now treated as something very, very serious especially after the show ‘Cheer,’” Khamphiphone said.

Something to Cheer About

“Cheer,” a docuseries that follows the Navarro College competition team on its road to the National Cheerleading Championship, was released by Netflix on Jan. 8, 2020 and went viral shortly after, as can be seen by this Google Trends report. The team and its coach, Monica Aldama, even appeared on “Ellen” and the “Today” show.

Paniccia, Comer, Monford and Allen also shared Khamphiphone’s sentiments concerning the show’s impact on how others perceive the sport.

“I’ve had a lot of people come up to me at college and pretty much say, ‘Wow, I didn’t know y’all go through that much like, how hard it is,’” Paniccia said. “So, I think like the attitude towards competitive cheerleading is starting to change, and it’s something I’m really excited about.”

Beecham said social media has also played a role in de-stigmatizing the sport for males as more people are able to see the intense stunts many teams perform and the “stud athletes” that can throw another person 15 feet in the air and then catch them.

As for the future of cheerleading, Monford, who also cheers for O.C. Elite’s All-Star team, said advances in stunting techniques continue to propel the world of competitive cheerleading forward. He hopes to one day cheer at the University of Kentucky, which has won 24 national cheerleading championships.

Yet, sideline cheerleading will always hold a special place in his heart.

“The thing I love most about cheering is like being able to just like see the impact that we have on our team, football or basketball. When we’re not there, our players ask where we were, our fans ask where we were,” Monford said. “Our presence is very felt and to me that really means a lot.”

Rachel Priest is a senior majoring in journalism and history in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, respectively, at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)

Telkom University

What is the title of Mary Ellen Hanson’s book on cheerleading?