Priyank Malviya, a computer science graduate student at the University of Georgia, feels that he doesn’t have an option in choosing his job. Malviya is from Lucknow, India, and he believes employers would prefer to hire someone from America, instead of dealing with visa issues. Malviya dreams of working for Google, but knows he would be willing to accept any job, even if it means working unusual hours.

International students like Malviya may wish to stay and work in the U.S. once they graduate, but this can be a difficult and lengthy process, especially if they want to stay in the U.S. long-term.

A Lengthy Process

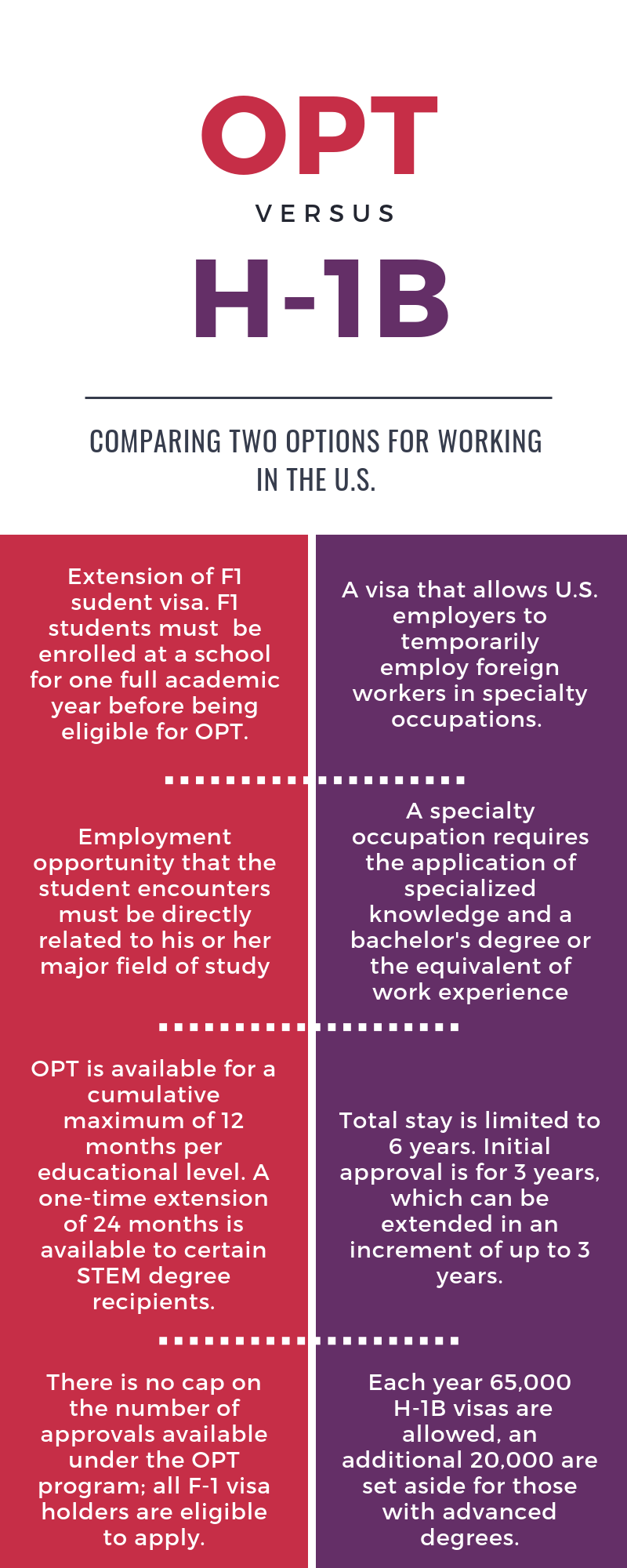

If international students wish to stay short-term — one to three years — there is the Optional Practical Training (OPT), an authorization granted by U.S. immigration authorities that allows students to work in their field of study, as an extension of their student visa.

The OPT is the nation’s largest source of new temporary high-skilled immigrant workers, with over 1.5 million foreign graduates authorized to work between 2004 and 2016, according to Pew Research Center.

International students can apply to OPT 90 days prior to the last day of classes in their final semester.

Jennifer Beasley, an International Student and Scholar Advisor at the University of Georgia Office of International Education, describes how the process of applying to OPT works for UGA international students.

First, students must go into their international student portal and request that the office recommend them for the OPT program. They are then issued an F20 form by the office, and a packet is then mailed to the U.S. government. Beasley notes that the approval process has increased over the last year, “a year from now it was taking 60 to 90 days,” for the government to approve a student to the program, but now it is currently taking three to five months, according to Beasley.

Beasley explains that this means that while the international student is waiting for the authorization from the government, they are unable to work or study and are unable to inform their employer when they can start work.

“They are basically just stuck and at the mercy of the government until they give them that OPT card,” said Beasley.

Luckily for international students applying for OPT, being denied is a rarity. “99.9% are approved,” Beasley explains. “I have been in this office 16 years; I don’t think I’ve ever heard of an OPT application being denied.”

For those who want to stay longer, there is the H-1B visa: an employer-sponsored visa that in most cases allows students to work for up to six years in the U.S. Each year, 65,000 H-1B visas are allowed, an additional 20,000 are set aside for those with advanced degrees.

The process for obtaining an H-1B visa is getting harder. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, changes to the application process for H-1B visas might potentially “discourage high-skilled workers from seeking employment in the U.S.”

Some of the changes include: an increase in requirements for demonstrating that a foreign worker possesses exceptional qualifications and the temporary suspension of “premium processing,” which fast-tracks applications for a $1,500 fee.

These changes have caused a significant increase in wait times: what once took two weeks is now taking many months.

An analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) data by the American Immigration Lawyers Association found that the “average case processing time surged by 46% over the past two fiscal years and 91% since 2014.”

This is the same problem Beasley stated is occurring with international students at UGA. Long wait times for both OPT and H-1B cause students to be left in limbo, unable to work and in some cases unsure if they can remain in the U.S.

A Decline in International Students

Anaa Tripathi, a UGA computer science graduate student from India, is currently applying for jobs in the U.S. He believes that because of the large number of students from India studying computer science, there are less jobs, and it can be more difficult to find employment.

While Tripathi feels like there are a lot of students from India studying computer science in the U.S., there is data to suggest the number of international students studying in the U.S. has been declining in recent years.

The annual Open Doors survey found new enrollment of international students fell by 6.6% at American universities from 2017-18. The major shift found was the number of students from India studying in the U.S. The survey found an 8.8% drop from the prior year in the number of graduate and professional students from India. India is currently the second-largest country of origin for international students in the U.S. after China.

This continues the trend seen in previous years. The number of international students from India enrolled in graduate level programs in computer science and engineering declined by 21%, or 18,590 fewer graduate students, from 2016 to 2017.

Declining numbers of international students could have a major impact on graduate programs. According to the National Foundation for American Policy, in 88% of the computer science graduate programs, the majority of full-time students in the program are international. This means that if the trend of less students from India continues, these graduate programs may not be able to sustain themselves, an October 2017 NFAP Policy Brief concluded.

Impact on Wages and the Economy

In recent years, some policymakers have blamed immigration for slowing U.S. wage growth. The Trump administration has been attempting to tighten up immigration policy. OPT is used as a pathway to the H-1B visa, a target of the Trump administration since reports that workers on the visas were replacing U.S. workers in tech jobs.

Unlike H-1B visas, OPT does not have a cap on the number of participants, so employers often hire workers on OPT, so they can be employed while trying H-1B lottery.

It is a common trend to go from OPT to an H-1B visa, said Beasley.

In my opinion those that go on OPT tend to lean towards employers that will give them the option of H-1B sponsorship.”

A professor of economics at UGA, Ian Schmutte, describes the two ways to look at how the labor market affects immigration policies. First, when workers are facing low rates of employment or stagnant wages, politicians decide to limit immigrant labor. This is based on the perception that doing so will limit labor market competition and therefore lead to rising wages or greater employment among native workers.

Second, firms may claim they cannot find workers with particular skills, such as skills required for tech jobs, so they therefore need to recruit skilled immigrants to fill the gap. In this setting, tech companies may lobby the government to expand the H1-B visa program.

Immigrants compete with native workers, this can influence wages by producing a downward pressure, but immigrants also put an upward pressure on wages because immigrants increase demand for goods and services, explains Schmutte. Immigrants also “contribute to innovation which can also stimulate wage growth,” said Schmutte.

If the OPT or H-1B visa is scaled back, it could have an impact on innovation, especially in the tech sector.

Analyses from Code.org, found that only 63,744 Americans graduate with computer-science degrees every year, but the U.S. has more than 500,000 open jobs in computing. Without highly-skilled immigrants, those jobs would go unfilled.

Karly Reece is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia. Reece is also pursuing a minor in sport management and a certificate from the New Media Institute.