You are having a health emergency. You call 911. The nearest hospital is an hour away.

You are diagnosed with cancer, but it took you months to find out because you don’t have transportation to see the one primary care physician in your county.

You finally get an appointment with a specialty doctor you need to see, but the closest office is two counties over, and you cannot afford it.

For rural Georgians, this is not just imagination; it is reality. Rural Georgia is struggling to access health care.

Physician shortages, hospital closures, lack of transportation, insurance coverage and broader education on navigating the health care system are all barriers to proper services for rural areas.

Seventy-five percent of Georgia’s counties are considered rural, according to the Georgia Department of Community Health. This means that 120 of the state’s 159 counties either have a population of less than 50,000 or are designated rural based on military exclusion.

Although rural areas are defined by their limited population, more than 25% of Georgians live outside urban centers and are affected by a lack of access to health care.

Surrounding Athens-Clarke County, the rural counties include Madison, Oconee and Oglethorpe County.

Physician Shortages, Transportation and Community Efforts

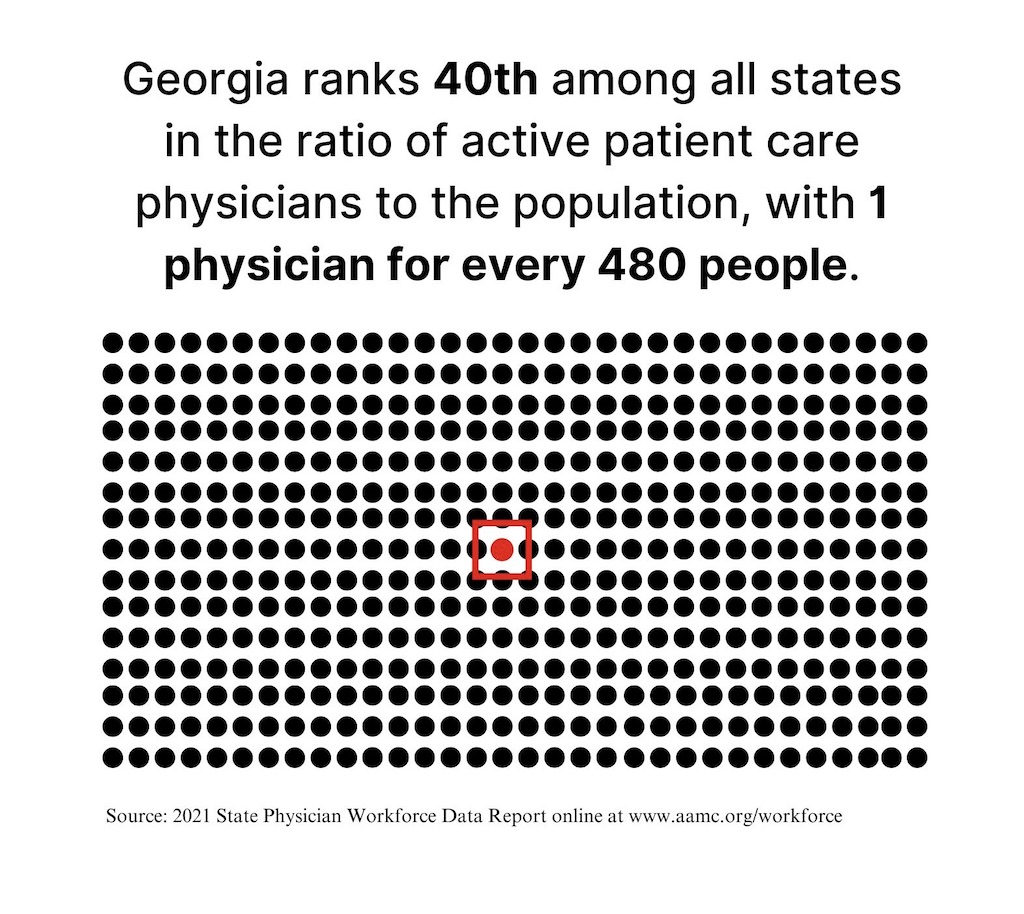

The physician shortage in Georgia is one factor playing a part in this complex statewide challenge.

Oglethorpe County has about 5,000 people per primary care physician. With more than 15,000 citizens, the county has two private primary care offices and one MedLink health center.

Oglethorpe County is not alone. One hundred forty-two of Georgia’s 159 counties are health professional shortage areas (HPSA). An HPSA is an area with 3,500 or more patients for every provider.

This shortage is emphasized when it comes to specialty care. Eighty-two counties in the state have no OB/GYN physician, 90 counties have no psychiatry physician, among other key medical specialists.

Although there are three physician offices in Oglethorpe County, citizens still often rely on 911 as their point of health care for subacute complaints that are not the best fit for emergency services.

“We noticed that we were running a lot of folks that had subacute complaints, just simply we were their access to health care,” said Jason Lewis, Oglethorpe County EMS Director. “And so we were sending paramedics out to situations where our complaints could be handled at an urgent care or a physician's office, and there's a variety of reasons why that is.”

Lewis listed insurance coverage, not knowing other means of accessing health care and transportation as some of the reasons.

Oglethorpe County is the 43rd largest county in Georgia, with a total land area of 439 square miles. This means it can take almost an hour to drive across the county. All three primary care offices are located in the central town of Lexington. Although the physicians' offices are within a half hour of most residents' homes, transportation is not always accessible.

This is an issue in other rural areas of Georgia. Three out of four counties in the state are health transportation shortage areas (HTSAs). These communities have high levels of transportation barriers to health care, ranging from public transportation availability to household poverty rate, depending on the county. More than a quarter of Georgia’s population lives in HTSAs, and an additional 16% live in borderline shortage areas.

Why It's Newsworthy: The lack of health care accessibility in rural Georgia impacts counties in Northeast Georgia, affecting people's quality of life. Ongoing state efforts such as the establishment of the University of Georgia School of Medicine have brought recent attention to the gap in services.Oglethorpe County works to fill gaps present in its community through partnerships and other services.

The county senior citizens center operates to take seniors to the doctor when they have difficulty driving or cannot drive. Also, to manage the load of 911 calls, the county EMS established a quick response vehicle equipped with everything an ambulance has except a stretcher and patient transportation ability.

Oglethorpe County emergency services also have strong relationships with the county school system and local families, with the goal of bridging the access gap and increasing education on navigating health care resources. Lower rates of health literacy, both personal and organizational, are barriers in some rural communities across the country, linked to factors including education and income.

“We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel. We just want folks to know how to use the wheels we have,” said Lewis.

Despite the ongoing community efforts, the sustainability of programs in rural areas is often a challenge due to funding.

Rural Hospital Closures

Oglethorpe County does not have a hospital, so emergency services transports patients to surrounding hospitals, largely to Athens. This is an added challenge the county’s citizens must face in accessing care.

But Oglethorpe is not the only county in the state without a hospital. Georgia is third in the nation for hospital closures. Since 2010, nine rural hospitals in the state have closed, and currently, 18 out of 30 rural hospitals in Georgia are at risk of closure.

“For any functioning organization, there are the expenses and revenues, and to run a rural hospital, it's more difficult to have a higher margin,” said Dr. Caroline Gomez-Di Cesare, Associate Professor of Medicine at the Augusta University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership. “It’s hard to recruit people to remote locations, so salaries may need to be higher to attract staff, while reimbursements may be decreasing.”

As Gomez explains, rural hospitals are caught in a cycle making it difficult for them to stay open. Rural hospitals struggle to recruit staff. Without a complete staff, it is difficult to safely staff full inpatient bed capacity, which further decreases the hospital’s revenue — making it harder to hire more staff and the cycle continues.

Insurance Coverage

Multiple other factors influence a hospital’s financial stability, one of these being insurance coverage. Hospitals do charitable work for patients without coverage, bearing some of the costs.

“Georgia has some higher risk factors for having rural hospitals in the red,” said Gomez. “For example, we do not have Medicaid expansion in the state, so we have higher numbers of the population who are without insurance.”

Georgia has the third highest number of uninsured people in the U.S. With 11.7% of the total population uninsured, the state falls behind the national average of 8%.

Sixteen and a half percent of people aged 18-64 in Georgia are uninsured. This is above the national rate of 11.2% of uninsured people in that age range. As shown in the map above, many rural counties in Georgia have rates higher than both the state and national averages.

Forty states plus Washington D.C. have adopted expanded Medicaid, but Georgia has not. Instead, the state implemented a unique Medicaid work program in July 2023 for people who do not already qualify for Medicaid in the state to obtain coverage.

To be eligible, Georgia residents must have a household income of up to 100% of the Federal Poverty Level and complete at least 80 hours of qualifying activities per month, including employment, job training and community service.

Although the state set a goal of 25,000 enrollees in the first year of the Georgia Pathways to Coverage program, only about 4,500 residents have enrolled. This is also far below the estimated 350,000 state residents who are eligible. The alternative program has cost Georgia at least $26 million, mostly in administrative costs.

Path Towards Solutions

“We’re still hopeful that there’s going to be some state or federal legislation that allows rural services more access to providers,” said Lewis.

Although communities around the state are working hard locally to close the rural health care access gap, ample resources and broad organization are necessary for sustainable effects.

Telehealth is one resource professionals have turned to, as many did during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although it could increase access to a range of health care providers, for rural Georgians, the absence of broadband internet connection is a barrier. About 16% of people in the state lack access to high-speed internet services.

Considering the range of health care access issues, the University of Georgia will establish a School of Medicine in Athens, hoping to ease the gap for rural communities.

“The School of Medicine will significantly expand the pool of medical professionals in Georgia, attract more top-tier scientists and researchers to the state, and produce more physicians to serve underserved and rural Georgia communities,” Jere Morehead, University of Georgia President, said in a UGA Today article.

In addition to the medical school, individuals, communities and organizations across Georgia are working to address the lack of rural access to health care in the state, including the CareSource Rural Access Advancement Program, the University Health Alliance, and many more.

“This is going to be a team sport to try to solve,” said Gomez.

Caroline Kostuch is a senior majoring in journalism and communication studies.

Show Comments (1)

Sara Huff

What an excellent article! As a retired RN, it is a shame & disgrace for our state of Georgia!

Why do we continue to vote for people who continue to allow this!!!