A 20-year-old rising college junior sits with a middle-aged woman on a sunlit Sunday afternoon in Copenhagen, Denmark. The two are in close contact, sitting only a foot across from each other on wooden platforms.

Colorful flowers are spaced around them, with leafy greens to balance the mix of purples, pinks and yellows. String lights hang from post to post, and a wooden swing-set is placed next to an overarching oak tree.

The area fits the criteria of a typical garden, except it is not a garden for growing plants but rather a space for growing relationships.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The Human Library’s concept of challenging stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination through one-on-one conversations has a potential to build bridges with individuals during a time where bitter divisions are steadily increasing.The student is there not for a date but to learn from and ask questions of someone with an above average intelligence quotient (IQ).

“So, what is your IQ,” asks Anant Sinha, a University of Michigan student studying abroad in Copenhagen.

“In the top 1 percent,” laughs Annette Bundgaard, signaling it was not the first time an individual has asked her that question.

The conversation between the two complete strangers comes courtesy of the Human Library, a place that is in every sense a true library filled with books. However, these are not books you carry with you to the beach for a summertime read.

The “books” are humans and are on “loan” to share stories one cannot grasp from a hard copy.

Located in the heart of Nørrebro, an area known for its vibrant and diverse scenery, the library brings together people from different paths of life and backgrounds through dialogue.

It’s often said: “don’t judge a book by its cover.” At the Human Library, individuals are encouraged to “unjudge” someone by reading a book (human) whose story is different from their own.

A “Pop-Up” Opportunity

The novel idea for the Copenhagen-based, non-profit organization comes from Ronni Abergel.

With his brother Dany and colleagues Asma Mouna and Christoffer Erichsen, Abergel created the library as a way of bridging curiosity and understanding in a traditional library format.

“We’ve created a safe space where you can explore diversity and meet people who represent a group in our community that’s often facing a challenge because of their ethnicity, religion, disability, orientation, lifestyle or even their social status,” Abergel said.

Recognizing the potential of encouraging conversations among unlikely pairings, Abergel presents the idea at a festival in Denmark, unsure if it would be a bestseller.

“When I saw how it worked, I thought there’s no community in the world that couldn’t benefit from having access to these conversations, because it’s a safe neutral space, free of political, religious or kinds of interest,” Abergel said.

For over two decades, the library has placed bookshelves in over 85 countries, including the United States. Abergel calls the library a “pop-up” opportunity, hosting events in schools, gardens and museums.

“It does the same thing as your community library,” Abergel said. “It creates an opportunity for you to learn.”

Checking Out a Human Library Book

“No talking rules” are a staple in traditional libraries. At the Human Library, no such rule exists. Open and honest conversations are not only allowed — but encouraged.

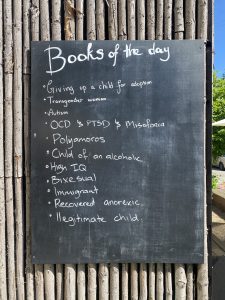

Human Library books cover a sweeping range of genres.

They are people who deal with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and misophonia. They are refugees and immigrants.

They have autism and anorexia. They are bisexual, polyamorous and transgender.

Regardless of one’s identity, readers are encouraged to read beyond the label.

“Because you sit human to human, the people that might have a conflicting point of view, they see a real human being next to them and see the human behind the diagnosis,” said Emma Stolten, one of 11 books on display at a reading garden event in Copenhagen.

Stolten published her story with the Human Library as a way of overcoming personal trauma, titling herself as, “Recovered Anorexic.”

“Every time I share my story, I let go of the shame of having a mental illness and of having anorexia,” Stolten said.

Conversations about trauma and isolation fill the green space as readers dive into the most intimate pages of each selected book and seek to understand the story unfolding before them.

Building Bridges in a Bitter Society

The library operates in a nonpartisan nature and implements boundaries of who can be published.

“We can’t publish anybody that will agitate for further intolerance and hate,” Abergel says.

Societal divides and polarization prove how urgent the library’s mission is across the globe.

A 2021 Pew Research survey found more than 60% of people in the world saying they are more divided now than before the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, 88% say they are more divided than before the outbreak.

Adapting to COVID-19 protocols and transitioning to an online setting presented a challenge for the organization that thrives on face-to-face connection.

“We lost a lot of resources and had to invest more in transitioning, but we’re then rewarded on the other side by all the people who then came back and said, ‘Wow, let’s try this online,’” Abergel said.

Recognizing the potential in virtual readings, the library is expanding on digital platforms, providing more opportunities to host reading events from anywhere in the world.

Acceptance Through Understanding

Before Bundgaard and Sinha departed from their 32-minute conversation, the duo thanked each other, not just for listening but for teaching each other something they didn’t know before.

“I’m surprised by how normal the conversation felt and how I was able to literally ask anything,” Sinha said. “It was more of just a casual conversation I’d have with a friend.”

The bond created by Bundgaard and Sinha is a reflection of the Human Library’s mission to challenge stereotypes and prejudices through dialogue.

“Of course it’s more satisfying to talk with people who keep it simple,” Bundgaard said. “But on the other hand, sometimes it’s interesting to challenge yourself to see things from another person’s perspective.”

Abergel says the library looks to “acceptance” over “tolerance” in bridging different people and lifestyles together.

“It’s very difficult to dislike and hate or have something against somebody that you got to know and you understood why they’re different,” Abergel said. “Through understanding we hope to reach some kind of acceptance.”

The exchange between Bundgaard and Sinha may seem ordinary, but amid bitter division, simply listening to one another can make a world of a difference.

Sydney Hood is a senior majoring in journalism at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)