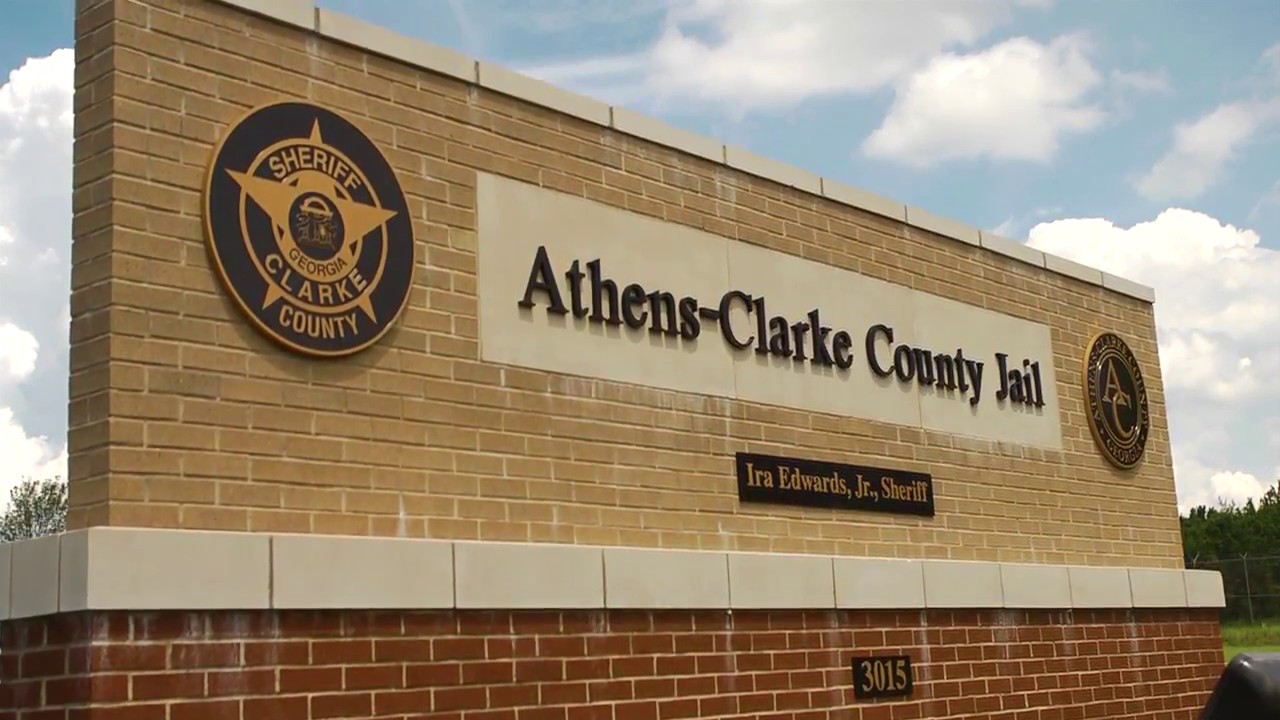

For spring 2019, 15 University of Georgia students spent their semester inside the Athens-Clarke County jail, but not as inmates.

One by one, they walk through the Athens-Clarke County Jail metal detector, allowed to bring only a pen and class materials into the facility. The students empty their pockets, leaving keys, wallets and even jackets outside or in a metal lock box in the corridor.

As they enter the classroom, the students sit down in a circle of neutral colored chairs being sure to leave an open space for the inmates. With a guard following closely, the inmates walk in wearing their bright orange jumpsuits with plastic sandals to match. They arrange themselves in the empty seats between the students.

The students are currently on week six of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, a course offered to upper-level students who willingly give up the comfort of a classroom for a unique look at the criminal justice system.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program provides pivotal knowledge to students who plan on a career in criminal justice. UGA students who leave this program are able to consider crime and punishment from a perspective that few in the field have experienced first-hand.

Sarah Shannon, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Georgia, is the director of the UGA Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program. She learned about the course from a friend and decided to bring it to UGA when she arrived in 2014.

“This program gives students a chance to actually see the people they are trying to affect as they advance in their careers,” Shannon said. “I think it’s important for the group to see first-hand how our criminal justice system treats people.”

During the eight-week course, Shannon urges using the word “student.” Structured like a seminar, she personally selects 15 UGA students, also referred to as “outside” students, to undergo an in-depth conversation that looks into our nation’s criminal justice policies. The outside students are accompanied by 15 inmates, referred to as “inside” students. While this is not your traditional classroom setting, Shannon expects inmates and UGA students alike to conduct themselves as professionals.

“I don’t think other UGA students will ever get the chance to experience this without actually committing a crime,” said Abby Campbell. Campbell is a fourth-year student at the University of Georgia studying sociology and criminal justice. During every class session, she sits between two Athens-Clarke County inmates that are twice her size. As an Athens native, Campbell has seen the disconnect between UGA students and the community of Athens.

“These aren’t bad people,” said Campbell. “It was easy to look past the jumpsuit because they are not only recompensing for their mistakes, but also making an effort to be better after they’re released.”

The Inside-Out Program was started nearly 20 years ago at Temple University by Criminal Justice Professor Lori Pompa. Pompa received the idea from an incarcerated man serving life in a Pennsylvania prison. The program was designed in the belief that “our society is strengthened when higher education/learning is made widely accessible.”

The U.S. began educating its prison population in 1965, and by 1972, inmates were able to take college courses funded by the Pell Grant. This did not last long. The government’s “Tough on Crime” attitude during the early 1980s drastically shifted our criminal justices system’s stance on crime and punishment. With a simple signature by President Clinton in 1992, incarcerated people became ineligible to receive Pell Grants and eliminated their access to postsecondary prison education.

Krohn’s primary focus centers on jails and prisons. Over the years, he has witnessed the decline of criminal education in U.S. prisons.

“When you look at the number of inmates in prison who don’t have a high school diploma, it’s sitting at 66 percent,” said Krohn. “ The current correctional education program offers classes, but it needs to revive its higher education courses.”

With higher education off the table, inmates have the option of only a high school G.E.D. This is where the Inside-Out Program comes in. Both inside and outside students gain a significant understanding of the criminal justice system by engaging in conversations, conducting academic research and undergoing practical application.

With the end of the program approaching, students were tasked with creating a proposal that could be implemented within prisons and jails of Athens-Clarke County.

For the spring 2019 semester, the students chose a proposal that would give people a chance to experience being processed through the criminal justice system. Each year, the proposal is presented to administrators from both the jail and the university to show merit. Shannon said that in years past, the jail has adopted some aspects of the class proposals. Outside students have also been known to follow through with plans after the program.

To date, the Inside-Out program has participants in more than 140 higher education institutions, including schools in Canada, Brazil, Germany and seven other countries across the world.

Shannon will begin the process of selecting a new group of inside and outside during the 2020 spring semester.

“We are in a situation where we all can all come together and realize our commonalities,” said Shannon. “And a lot can be produced from meeting someone as another human being.”

Tyree Brown in a senior in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.