The city of Athens is home to the University of Georgia, a school known for its spirit, academics, and impressive athletics. The town is regarded as “one of the best college towns in America,” with its vibrant college life scene, football team and charming Southern feel.

Go a little further off campus, however, and you’ll see the reality of Athens-Clarke County.

Public housing facilities stand just down the street from the stately mansions of South Milledge Avenue, one of the main thoroughfares in Athens and home to hundreds of students in fraternities and sororities.

With a poverty rate of 32.4%, (that’s 37,162 people), Athens-Clarke County (ACC) is one of the poorest counties in Georgia. Children growing up in poverty are among the most vulnerable.

According to a New York Times data visualization published in 2018, children growing up in poverty in the ACC area are expected to earn an average annual salary of only $21,000.

This finding emphasizes the cyclical issue of poverty in ACC—so what does that mean for the children affected by it?

The Cost of Youth Poverty

These problems go deeper than the surface—they’re the product of physiological changes happening in impoverished youth.

Studies conducted by Duke University show that poverty affects brain growth, and the difference can be seen as early as infancy. Infants living in poverty showed a different trajectory of development as early as age 2, suggesting that the longer the child is exposed to an impoverished environment, the greater the difference in brain development.

In ACC, 1 in 4 lives in poverty. But the issue goes further than socioeconomic status.

Athens-Clarke County, home to the @universityofgeorgia, is one of the poorest counties in Georgia, with 39.3% of its citizens living below the 150% poverty rate. So what does that mean for ACC youth?

— Wellsley Kesel (@KeselWellsley) April 4, 2019

According to a study conducted by the New York Academy of Sciences, “children raised in low‐income families are at risk for academic and social problems as well as poor health and well‐being, which can, in turn, undermine educational achievement.”

The brain images of children living in poverty also showed unusually high levels of cortisol (a hormone produced by the body in response to stress or danger)—similar to children who were physically abused. That leads researchers to believe stressful circumstances might be the common denominator.

The delays in brain growth and development can also affect educational achievement and executive functioning.

Statistics from low-performing elementary schools in the ACC area such as Gaines Elementary School support the correlation between low-income households and struggling academic performance.

At Gaines Elementary School, located in the heart of Athens, 92% of students come from low-income households. Test scores also rest far below the Georgia state average, with only 15% of students proficient in math and English, compared with the state average of 40%.

The hunger gap that many students experience in Athens-Clarke County also plays a large part in their overall development.

According to 2017 data collected by the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning, an average of 92% of students at 20 elementary schools in ACC are on free or reduced lunch.

To put this statistic into perspective, neighboring Madison County has a much lower average, with 65% of students on free or reduced lunch.

University Disconnect

The difference between the two worlds in ACC is glaringly obvious. At UGA, the majority of students come from privileged households, with the median family income of students being $129,800. Only 3.8% of students are from the bottom 20% income percentile.

The ‘University Bubble’, otherwise known as the disconnect with reality UGA students have in their tight-knit groups and organizations, makes it hard for students to recognize the community outside their immediate circles.

Food2Kids is a UGA organization that partners with the Northeast Georgia Food Bank to provide weekend meal packages to children who are facing food insecurity. The packages are used to help eliminate the “hunger gap,” the time between the last meal at school on Fridays and the first meal on Mondays.

Vallie Candler, co-president of Food2Kids, speaks about the gap that has formed between the university and the surrounding town of Athens.

“The [University Bubble] is very real within our campus community. We are all so blessed to pursue an incredible higher education, and we have been given opportunities throughout our lives to grow and pursue our dreams,” Candler said.

Candler urges university students to volunteer and become hands-on within the Athens community.

“We meet every Wednesday at 5:30 p.m. at the Food Bank of Northeast Georgia, and our ‘baggings’ only take 30 minutes to an hour of your time to make such a difference,” Candler said.

The Mentorship Effect

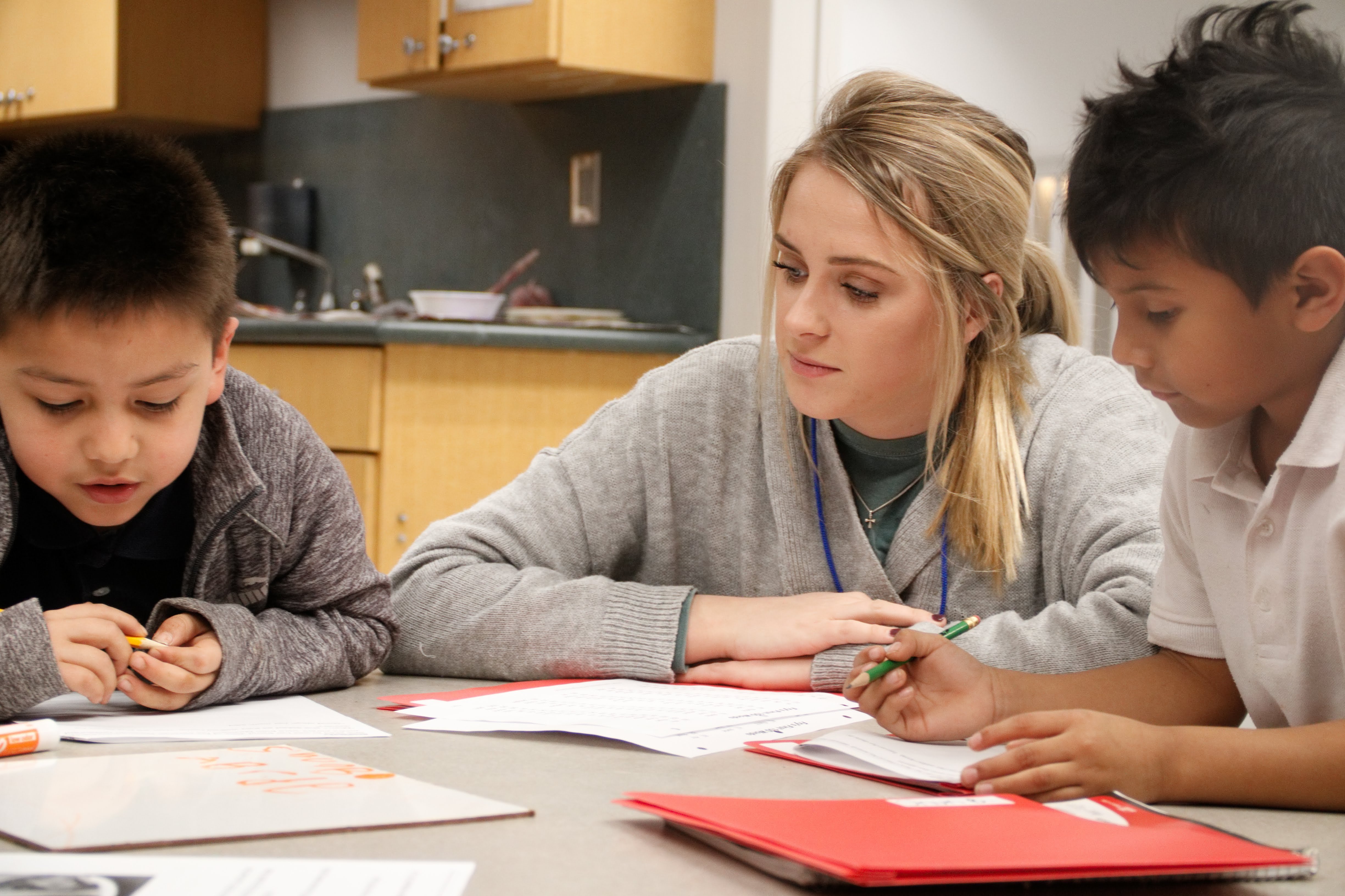

One of the most important issues in childhood poverty is that children often do not have positive role models to guide them in critical developmental years.

Researchers at Merrimack College found that impoverished students receiving mentorship had improved outcomes in “their perceptions of parental relationships, scholastic competence, and school attendance.”

While the findings did not directly affect self-worth, values of school, and grades, these categories may have been mediated by improved perceptions of parental relationships and scholastic competence.

Karen Higgenbotham, director of the Office of Early Learning for Clarke County School District, emphasizes the importance of having a “buffer” in children’s lives.

I think the more opportunities [kids] have to be involved in support systems, it’s beneficial. Often times it’s the engagement that makes the difference. By having a mentorship, you’ve got someone else who is helping to provide a buffer, to provide a safe space.”

This theory proves true for Lemuel LaRoche, the founder of Chess and Communities, a non-profit organization that helps underprivileged kids learn chess and develop critical thinking skills.

“At Chess and Communities, we’re developing another generation of thinkers, of strategists, of kids that see all aspects of their community… because ideally they’re being trained to lead the community in some aspect.”

LaRoche refers to the kids that come through his program as “young kings and queens” a reference to the game of chess, but with a deeper meaning.

“It’s so important for their self-esteem. Everything they see is programming them to be negative, to think negative, to project themselves and see themselves as being non-productive, because that’s what we see in media and newspapers,” LaRoche said.

“We have to reverse that process by constantly implanting in them that ‘y’all are young kings and queens—now act accordingly.’”

Moving Forward

While the case of childhood poverty in Athens is a complex issue, the work of community and university organizations is helping to spark the conversations necessary to impact children’s lives.

Organization leaders like LaRoche are hoping to spread awareness to reach more kids.

“We’re trying to get more volunteers, get more people engaged, get more people involved in what it is we’re doing, and really, get the capital that’s needed to really take what we want to do to another level, so we can reach more and expand what we’re doing in other cities,” LaRoche said.

Other state-run programs like the Georgia Head Start Association, help to provide young children with elementary school preparedness.

Higgenbotham emphasizes the importance of early intervention, as early as 8 weeks old.

“The best way to avoid a gap is to never let it get created in the first place. By having the early learning programs directly connected and aligned to the school district, students can really come in with a strong foundation and be truly school-ready when they begin Kindergarten,” said Higgenbotham.

“The more we can increase our services early, the less intervention we need later.”

Wellsley Kesel is a senior majoring in journalism with a minor in sociology at the University of Georgia. She is completing a certificate in New Media.