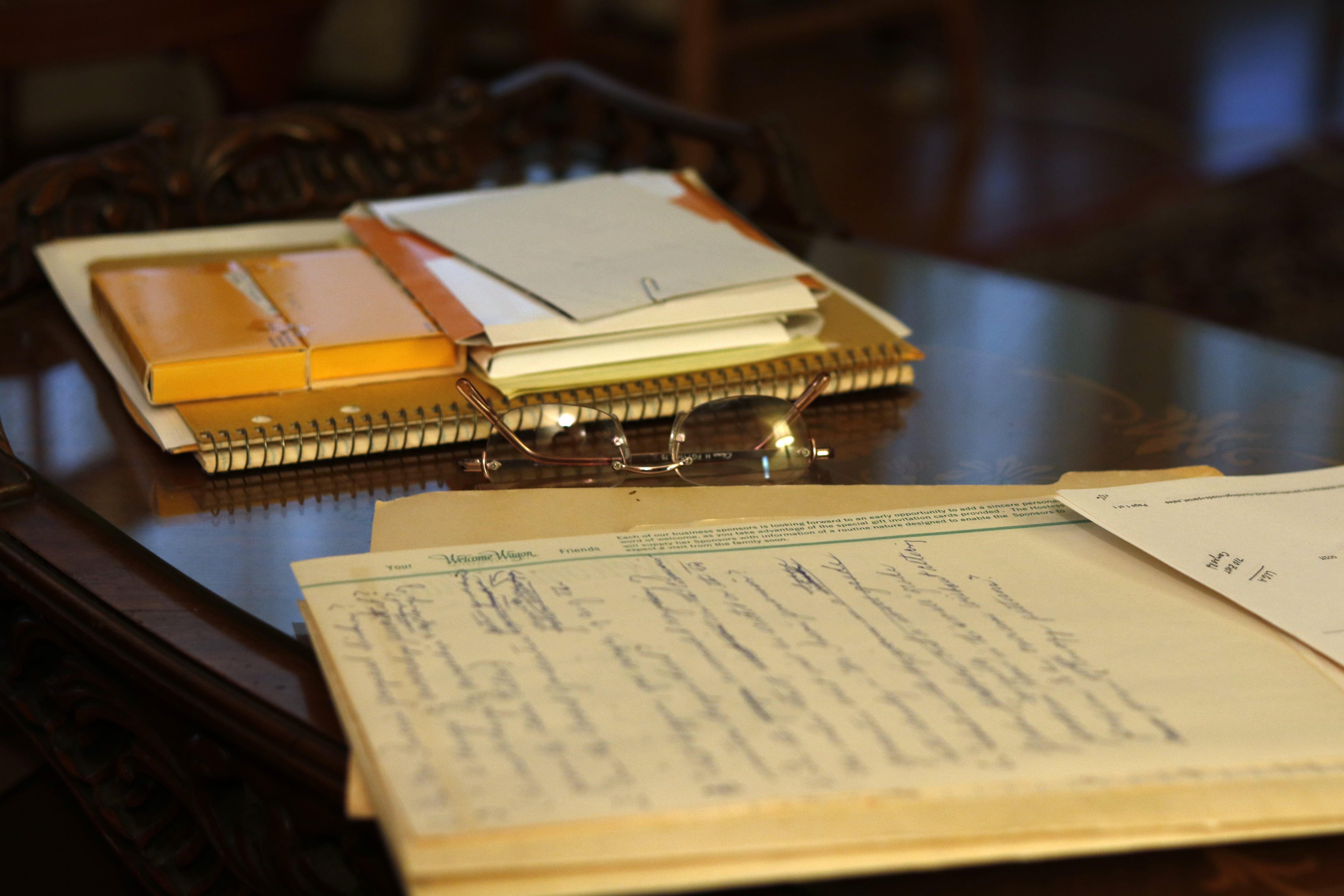

Sifting through topographical maps and old paperwork, Dora Duncan, 93, points out just how much has changed since she first bought her home in 1965. As someone who has been a resident of Riverdale Drive for the past 53 years, Duncan has experienced zoning fights, studentification and the more recent gentrification of her once quiet street.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Although Duncan’s perspective is personal, her experiences reflect how students can change the demographic of a neighborhood and overall affect the Athens community.

When she first moved in, East Campus Road did not exist. Family Housing, which is right around the corner, had not been built. To the left of her home was all empty land. She knew all of her neighbors and can still list each one house-by-house.

The street was full of reputable professionals, as Duncan said. University employees, nurses and city government officials lived on the street. There was even a duplex exclusively rented to police officers.

Over time though, things began to change. Families grew and moved to larger homes. Older residents went to nursing homes. Gradually, students started moving in. The neighborhood first saw graduate students with families, or younger working couples. Duncan considered them responsible, mature adults.

Beginnings of Studentification

Around the same time, houses on the street started becoming rentals and with that the maintenance was minimized. At one point, Duncan said the house across from her became a temporary fraternity house as the fraternity was kicked off campus. Car doors slamming. Congestion on the street. Between work and zoning battles, Duncan and her husband didn’t have time to fight with the young neighbors. Duncan said they decided to just live with it.

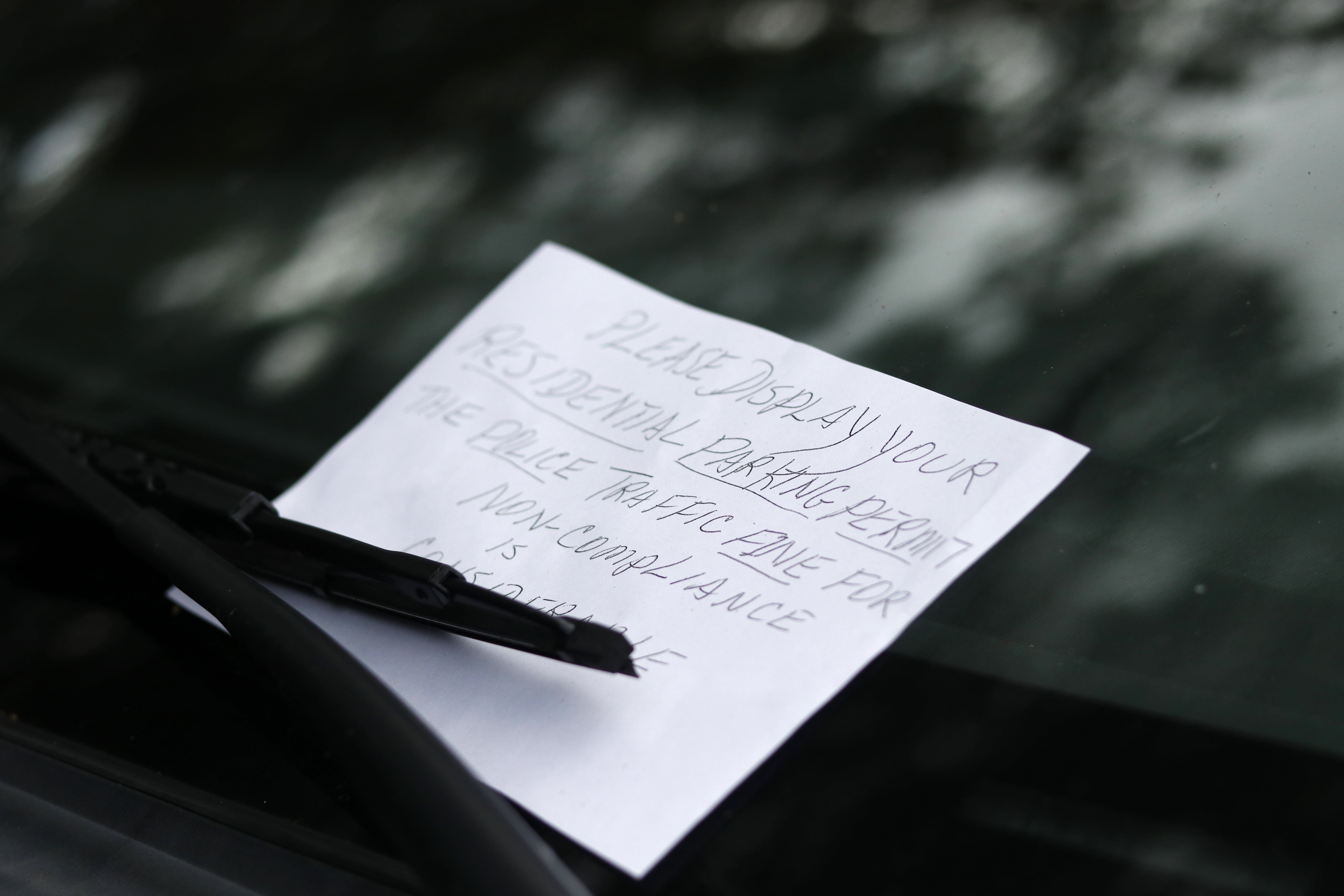

Although Duncan has no control over who lives in the neighborhood, the one thing she’s continued to monitor is who’s parking on the street.

“Who’s patrolling all of this?” Duncan asks. “[There are] so few of us [permanent residents] left, but the one thing catch patrolled is the street.”

In her home, Duncan has a photocopied stack of handwritten notices she places on cars parked illegally. Without a permit, between the hours of 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, nonresidents may not park on the street.

Since the university started charging for parking in the early 2000s, Riverdale Drive became a campus parking lot.

You have no idea.” Duncan continued, “You just could not look down the street. It was just parked all the way. You could never be sure on parking space. Students talking in front of your house. Foot-traffic. Student traffic. The street was a parking lot, just like a Christmas shopping lot.”

It took three to four years of residents going to city council meetings and objecting the public parking on the street before it became permit only. Duncan said part of the reason why it took so long was that there were not enough permanent residents on the street. Of the 27 houses on the street, Duncan estimates that currently only six or seven are resident owners.

In order for a street to become residential parking only, The Athens-Clarke County Transportation and Public Works Department policy states a petition of 65 percent of the property owners along the street is necessary to support the approval of the permit. The policy clarifies that the “property owners” cannot be the owner of a townhouse, condominium or property with more than four units. Therefore, it contains the passes to single-family home neighborhoods.

Riverdale is one of the 27 streets approved for residential permit parking. These 27 streets share a common theme. They’re all near campus, and therefore subject to overflow parking by students and visitors.

Future of her Home

As for the future of her street, Duncan believes that the changes beginning in Five Points are going to seep their way into the neighborhood. Recently, Five Points residents have been pushing back on infill housing.

You look around Five Points—ostentation and gentrification is the name of the game,” said Duncan.

In a Flagpole article from 2016, Five Points residents opposed the boom of infill housing because of the scale of the homes and increasing taxes. Older homes were being demolished to make way for larger ones. A solution offered in the meeting was to make the street a designated historic district, which would save the houses from demolition and freeze taxes for seven years.

Unfortunately for Duncan, Riverdale Drive doesn’t fall under one of the local historic districts. Therefore, residents and renters can change the appearance of their homes without regard for historical merit. Duncan calls the renovation of homes on Riverdale Drive abominable.

The houses may not have been cutting-edge beauty, but they fitted in, and to paint over brick ought to be recorded by St. Peter,” said Duncan.

When it comes to accountability, Duncan believes the responsibility lies within city governments and enforcing the rules set in place. The faults she has with city supervision are that there are so many lapses in rules that they go unenforced—like her having to patrol the street because local police have not.

Becca Beato is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.