Greasy pizza boxes, single-use coffee cups and plastic bags are commonly used items, and people often wonder whether these types of items can be recycled. Now, an artificial intelligence bot on social media may be able to answer the question—“Can I recycle this?”

Misplaced materials are common, and these incorrectly recycled items contaminate batches of recyclables, causing them to be thrown away. This problem motivated Katherine Shayne and her team to efficiently communicate information on recyclability—using social media as a platform to inform people of local recycling and composting rules.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The implementation of an AI bot on social media profiles is an innovative solution to the waste generated by incorrectly recycled materials. This technology could ease the lives of ACC residents by providing accurate recycling information quickly, while promoting sustainability in the community.

Shayne, an alumna of the environmental engineering master’s program at the University of Georgia, is the CEO and co-founder of Can I Recycle This, Inc (CIRT).

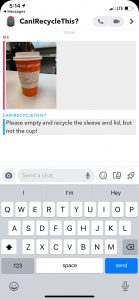

Can I Recycle This is a social media profile on Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon Alexa and Facebook. On Facebook and Alexa, an AI bot named “Green Girl” answers direct messages inquiring about materials. Users submit or describe an image and their location, and the bot will respond with whether or not the item is recyclable.

“We’ve made a platform to where you can ask or send a picture of any item, and it’ll give you a response based on where you asked,” Shayne said. “So you are wondering about a soda can and you’re like, ‘I don’t know this recyclable here.’ You can take a picture of it, and it’ll tell you based on your location.”

Answering Common Questions

The “Green Girl” profiles respond to descriptions and photos. Submitted pictures are first scanned by the AI bot to determine what the item is using keywords—such as brand, color and material type—associated with the image. Then, the AI bot sends the gathered attributes to the company’s database, which contains a log of recyclable items by location. Based on information stored in the database, the AI bot will respond to the user’s direct message accordingly.

“What’s recyclable in Athens is not necessarily what’s recyclable and St. Louis, or San Francisco or Dallas, Texas; it’s all very, very different,” Shayne said. “What we also learned is that a lot of [local information on recyclable items] is still very archaic, and I say archaic because it’s still like billboards or print media, or things that you actually have to have a handout or a mail out.”

The AI bot is currently only active on Facebook and Alexa. CIRT interns still answer direct messages on Twitter and Instagram, while Shayne answers Snapchat messages. The AI bot for Twitter has been built, but it is not active on the platform, Shayne said.

Continuing Development

Shayne said even though the bot can identify color, it is still learning how to recognize food. For example, greasy pizza boxes are not recyclable. Currently the bot does not recognize grease. So by default, it will tell the user to recycle the top half and compost the bottom.

Jessica Mitchell, a sophomore geology major at the University of Georgia, is the company’s social media intern who answers direct messages on Twitter. She also develops recycling education materials and attends outreach events.

“It can be confusing to know what you’re supposed to recycle because it’s so different everywhere, which is what we’re trying to solve,” Mitchell said.

(Screenshots/Victoria Swyers)

According to Mitchell, most of the submissions received come from Snapchat and Facebook. The Twitter profile receives about five submissions per week. Shayne said the Snapchat profile receives up to 15 submissions per day.

“I don’t think it’s very common knowledge to know like the little nitpicky details,” Mitchell said. “So, I don’t think contamination is really something you can blame on anyone. It’s just something that education needs to improve on.”

Unforeseen Complications

Misplaced recyclables may seem harmless, but they could contaminate the properly recycled materials. This creates an undesirable product that is not purchased by third parties.

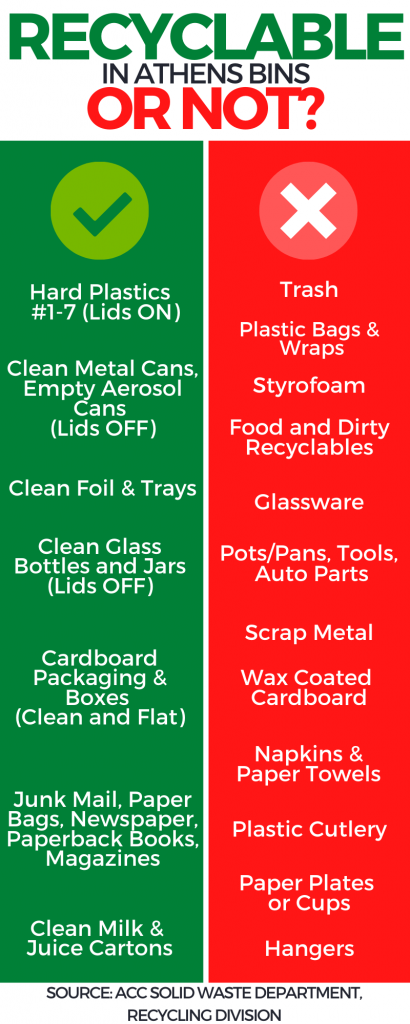

The difficulty with implementing solutions arises because each recycling facility differs in the materials they accept. Some facilities are not equipped to deal with materials that are harder to recycle, but in Athens, these items may be taken to a separate facility, CHaRM, and are listed on their website.

Bales of sorted recycled materials created and stored by the Athens-Clarke County Solid Waste Department, Recycling Division on Friday, February 21, 2020 in Athens, Georgia. The bales are eventually sold to third-party buyers. (Photos/Victoria Swyers)

Mason Towe, recycling program education specialist for the Athens-Clarke County Solid Waste Department, said the amount of recycling thrown away due to contamination is hard to quantify, but the department can estimate the facility’s residual rate.

“The residual rate is the percentage of stuff that goes to the landfill that was in the recycling facility. So, that’s non-recyclable items, hard to recycle items and recyclables that are dirty or got missed. That’s typically on average between 10 and 15 percent,” Towe said.

The items included in the residual rate are thrown away.

According to Towe, increased contamination could negatively affect job availability and working conditions. If third parties charge more for cleaner materials, it could affect the amount of employees the facility hires.

“It’s already a tough job—just going through the material as it comes through and sorting it by type, and then you add the the layer of determining whether it’s clean or dirty, whether it’s the correct item and then also having to deal with the smell and pests that come with the food and other things,” Towe said. “I think making the material a better stream coming in is a great way to improve employee retention, and it just makes it an easier job for them for sure.”

Wishful Recycling

According to Towe, after 2011, contamination increased because more people began recycling after Athens changed from a dual stream—separate container for each type of material—recycling system to single stream—one container total.

“We’ve seen more material coming to us, but also with that comes more of the wrong stuff, unfortunately,” Towe said.

The University of Georgia Office of Sustainability’s position on the issue is “when in doubt, throw it out.”

“Wishful recycling” does more harm than good, Kevin Kirsche, director of the Office of Sustainability, said in an email. “Can I Recycle This? is an innovative strategy to help consumers make informed waste management decisions in real-time.”

Kristen Baskin, founder of Let Us Compost, has been working closely with Shayne through the New Materials Institute. Baskin said food is the number one contaminant of recyclables.

“Taking food out of recycling—you compost it, which is amazing—brings value back to the recycling stream,” Baskin said. “And long term, bringing [value] back into the recycling stream means that our cities are actually making money recycling as opposed to losing money on it. So on top of the incredible environmental impact, it’s a way for [cities] to be sustainable.”

Can You Recycle That?

Towe said the question “Can I Recycle This?” is actually posed to the department by residents often. Employees of the office respond individually to the questions on what is trash and what can be reused and recycled.

“We’re happy to answer those questions,” Towe said. “But the less we have to answer individual questions, the more we can do on broader education to more people.”

Towe worked with Shanye and her team to provide frequently asked questions for her AI bot.

Companies that develop separate apps are nice, but when people run out of storage space on their phones, the apps are deleted, Towe said.

“[The fact that] it’s accessible for anybody—that has Facebook or Twitter, any of those—to be able to use it quickly is really cool,” Towe said.

Increasing Accessibility

However, Towe also pointed out that limiting the AI technology to social media platforms could exclude older generations that don’t use social media. Individuals unaware of the “Green Girl” profiles and those without access to those platforms could also be excluded, Towe said.

“I’m sure that the millennial generation will be fine with pulling up their app and taking a picture and saying, yep, it’s recyclable—put it in there. But, it’ll be interesting to see how it works community wide,” Towe said.

According to Shayne, CIRT is building an app. However, their company data shows that people engage in the social platforms already on their phones.

Shayne said she was surprised to find that a lot of middle-aged adults interact with the technology on Facebook messenger. However, she also said engagement varies based on community events. For example, UGA football games cause engagement to spike. CIRT also uses promoted ads on Facebook to reach older demographics.

Towe said implementing similar technology globally could also be a problem due to cultural norms. For instance, different recycling regulations and technologies could make the expansion of this technology and similar programs difficult, especially across different locations.

A Growing Company

Shayne said the biggest limitation for CIRT is expansion. CIRT faces the same problems that exist with most startup companies. Pitching ideas to larger businesses and rate of adoption are two examples of how the company is experiencing growing pains. The company is working on expanding marketing strategies with a firm in Athens.

CIRT co-founder, Jenna Jambeck, is a professor in UGA’s College of Engineering and internationally recognized for her work with marine debris. Previously, Jambeck had a start-up company that failed. As a result, her advice and guidance has been vital to understanding what not to do, Shayne said.

“We have basically created a product that works, that is sellable, but it’s not perfect,” Shayne said. “So we’re consistently updating it, giving it new information, making it better—so we’re selling a product that is continuously learning.”

Adapting the Product

As cities change what items its recycling facilities accept, the technology will have to learn and integrate the new rules into its database.

Athens is one of 10 cities that the company has developed a database for. The five sites with contracts are Athens, Georgia, Columbus, Georgia, St. Louis, Missouri, Menlo Park, California and Palo Alto, California. The other five sites are developing contracts and cannot be announced yet.

Athens and Columbus are the only two cities currently with active technology, but the others will begin in the next few months, Shayne said.

The CIRT team cultivated the recycling data manually from each city to implement into their database for the AI technology.

Aside from social media platforms, CIRT is expanding to work with an unnamed “online marketplace.” CIRT also hopes to expand with food delivery services to let purchasers know what items in their boxes are recyclable. Shayne said the goal is to continue implementing the technology in cities across the country.

“I always want [the world] to be a better place for [my little sister] and for everyone and for generations to come,” Shayne said. “I don’t want them to be plagued with tons of plastic in the ocean.”

Victoria Swyers is a senior majoring in both journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and ecology in the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)