What was once a highly rewarding career is no longer for some educators.

“I taught in the 90’s, throughout the whole 90’s… I had a lot of autonomy when I was teaching,” said Greg Davis, who taught fourth grade for 16 years, and now serves on the Athens-Clarke County Board of Education. “There were less state requirements. The philosophy of education has changed quite a bit.”

The U.S. education sector makes up a significant portion of the workforce. In the 2019-2020 school year, approximately 3.2 million teachers were employed in public schools.

However, recent research suggests a national and state-level teacher exodus is underway.

Why It’s Newsworthy: A 2022 survey showed that 55 percent of U.S. educators are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than they had planned. Meanwhile, the national percentage of students majoring in education is steadily declining.In Georgia, this trend is apparent.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Education, during the 2021-2022 school year, Georgia teacher shortages were apparent in subjects such as mathematics, special education, social studies, science, various world languages and physical education. Grades K-12 were affected.

In the past few years, the University of Georgia’s College of Education has experienced a rapid decline in students enrolled. As of 2021, there was a 33 percent drop in the number of students who wished to pursue elementary education.

It is yet to be seen how this might impact Athens-Clarke schools and surrounding county schools in the years to come.

“I don’t think that Clarke County is any different from what’s happening throughout the country,” Davis said.

A survey conducted by the Georgia Department of Education asked teachers if they were likely to recommend the teaching profession to upcoming high school graduates. A staggering 66.9 percent of teachers answered that they were unlikely to recommend pursuing a career in teaching. Only 2.7 percent of those surveyed said that they were very likely to recommend it.

Davis said part of the reason for teacher shortages may be attributed to the fact that some teachers are portraying the profession in a negative way.

“When you start talking about what creates the shortage, it’s not an economic thing. It’s about how the profession is being sold,” Davis said. “And your number one salesperson in public education are your teachers.”

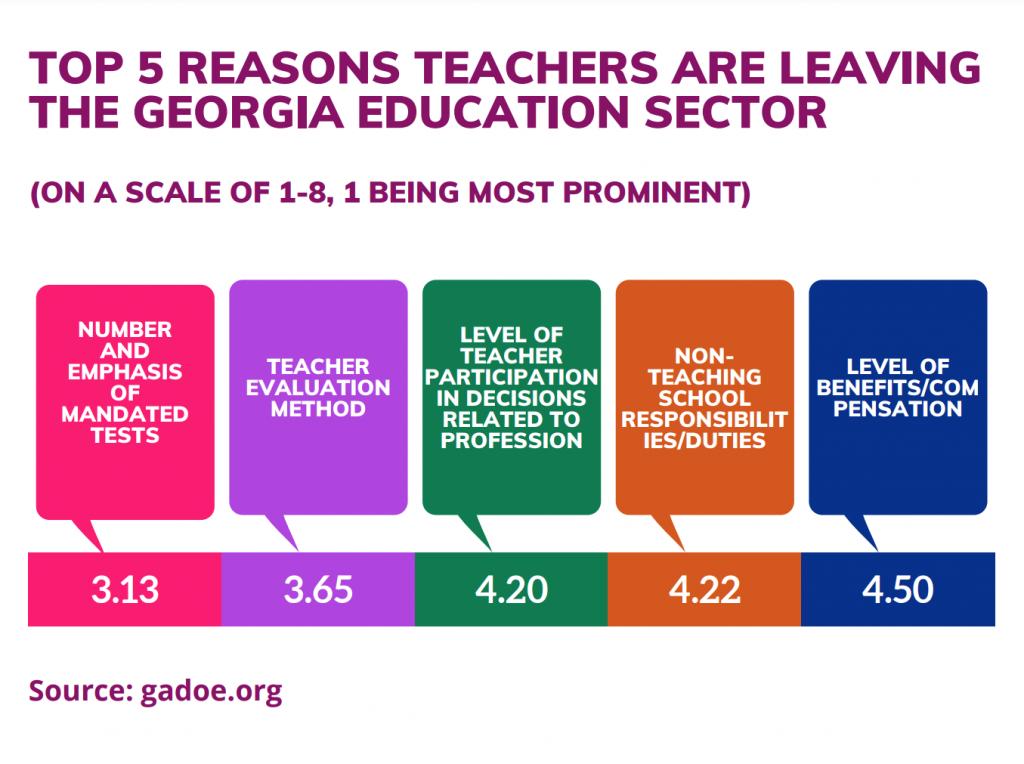

The same Georgia DoE survey revealed that teachers were dissatisfied in a number of areas. Some reported dissatisfaction with the amount and frequency of mandated tests, while others were unhappy with the provided compensation and benefits. Teachers also reported discontent with performance evaluation methods and the amount of non-teaching duties assigned to them.

Those surveyed were asked to rate issues on a scale from one to eight, one being the highest priority issue, and eight ranking the lowest.

The Georgia DoE surveyed 53,066 Georgia teachers in 2015. Those surveyed ranked provided reasons for teacher dissatisfaction on a scale of 1-8. (Graphic/Haley Chambers)

Davis said in Oglethorpe County, teachers voiced similar concerns during school board meetings.

“Large numbers of teachers at Oglethorpe Elementary unhappy with the leadership there, and feeling like they aren’t being listened to,” he said.

The COVID-19 pandemic undoubtedly added a degree of stress and uncertainty to a job that already presents challenges.

According to a report by the Rand Corporation, nearly half of U.S. public school teachers surveyed who left teaching after March 2020 and weren’t already scheduled to retire did so for pandemic-related reasons.

“At least for some teachers, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have exacerbated what were high stress levels pre-pandemic by forcing teachers to, among other things, work more hours and navigate an unfamiliar remote environment, often with frequent technical problems,” the report stated.

When schools transitioned back to meeting in-person, the responsibility to enforce masking and COVID-19 hygiene fell largely on the teachers.

“Some of the parents were not as supportive as they could have been when it came to educating their kids about masking and stuff like that. It became our job to not only teach, but to make sure the kids were being safe. We had to protect ourselves, too,” said Zachary Davison, sixth-grade ELA teacher in Marietta.

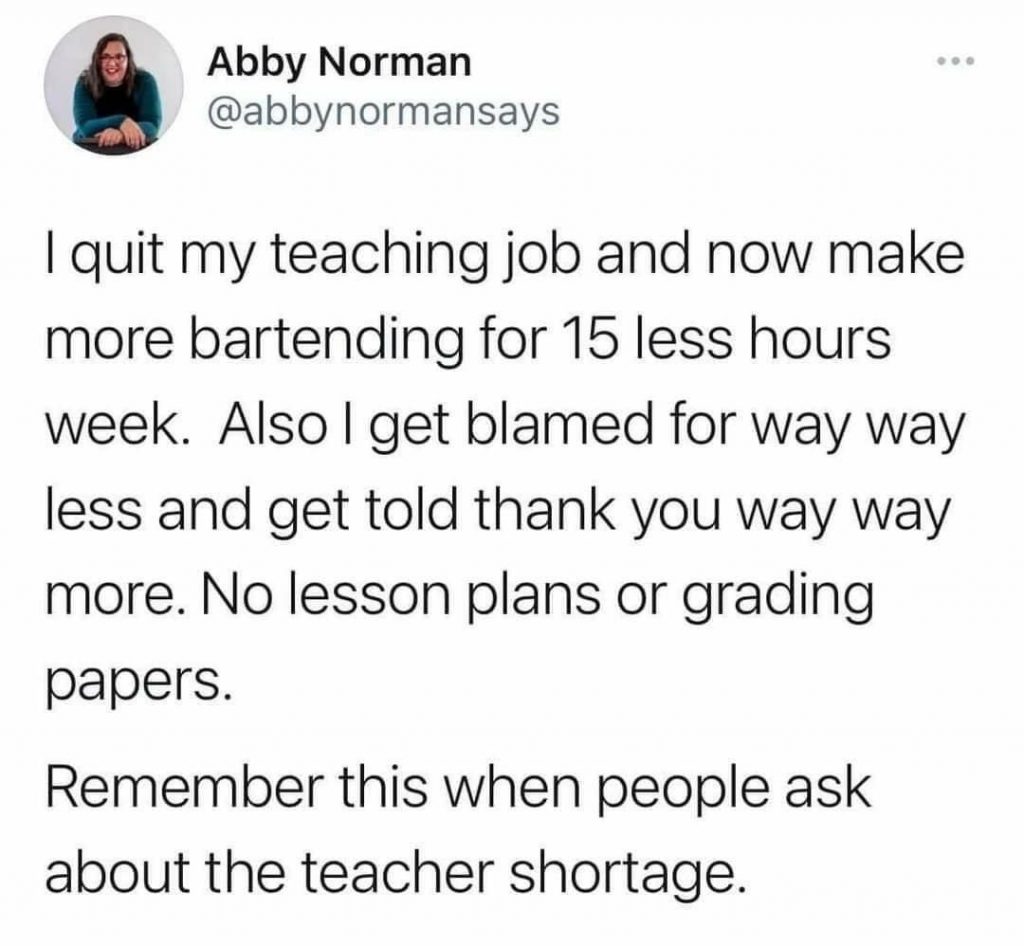

Teacher pay is also a factor in decreased satisfaction with the profession. While pay varies depending on location and level of experience, some teachers feel that they are being overworked and underpaid.

Abby Norman is now working as an Atlanta area pastor, author and bartender.

“We’re asked to work past our contract hours, grade and lesson plan and do professional development without being paid for those hours,” Davison said.

Georgia lawmakers have begun introducing legislation in an attempt to alleviate the statewide shortage. Under HB 385, retired K-12 teachers with at least 30 years of experience would be able to return to the classroom full-time. Those who chose to return would receive retirement pension as well as salary. If the bill is signed into law, it will go into effect July of this year and remain until July 2026.

Davison says he has no immediate plans to leave the profession, but he advocates for increased teacher salaries across the board.

“Pay us a living wage. Begin to forgive student loans after five years of serving. I think that’s a start in the right direction,” he said.

Haley Chambers is a student majoring in journalism at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (11)

Darrell David

It’s eye-opening to see how the education landscape has shifted for Georgia teachers. Your blog sheds light on the challenges they face and the resilience they show. Thanks for sharing these important insights!

Michael Hiett

As a special education teacher for 15 years, would never have entered the field of education had I known the future it would give me. I desired to teach PE and health with my degrees in psychology, health sciences and public health. However, I took many certification tests to make myself marketable. By taking and passing the special education test, I have been forced to remain in the field because our contracts allow administrators to do whatever they want with us. When I hear of the “shortage” I find it laughable because in my experience we are treated like we are replacable. After 2 years of high school sped in one district I needed a change because those kids were too big and violent. I asked to transfer to one of the many available elementary or middle school vacancies but was told I was not allowed until I worked 3 years at the school where I was hired. I didnt sign my contract for a 3rd year at that school because that was my only out. They also said I was uneligible to be hired at another school because I didnt sign my contract. Really? So I went to another district. My evaluations were excellent and state that what I did “should be emulated”. Yet I was disposable. Why is it I sign a contract for 1 year yet they can control me beyond the contract like that? Its bad enough they expect more than 1the number of days listed in the contract. In my opinion, this career has not resulted in the life I expected and it is closer to enslavement rather than employment. I have many examples of what I believe to be abusive administrative practices towards others and towards myself. There are no real checks and balances regarding admin and district employees. All blame and emphasis appears to be on teachers. My wife and I, both teachers, made in known to our 3 children that we will not support them financially in college if they choose education as a major. We want them respected and happy in another field.