Looking at concessions alone, sporting events produce a considerable amount of waste.

Denise Plemmons, the waste reduction coordinator for the Athens-Clarke County Recycling Division, said the landfill typically receives an additional 35-40 tons of landfill waste after a University of Georgia home football game.

According to the University of Georgia Athletics website, that increases to an average of 72 tons of waste after an SEC night game.

Plemmons said about 300 tons of trash is brought to the ACC landfill every day, so at that rate, the landfill has about 37 years left before the ACC Solid Waste Department would need to outsource this work, transporting Athens’ garbage to landfills outside the city.

This would not only be more expensive for residents, but would burn more fossil fuels in transportation.

“People don’t have a connection to their trash,” Plemmons said. “It does not magically disappear.”

Plemmons said the current waste stream is an issue because once something is thrown away, the resources are wasted in a landfill. On the other hand, compost can be used to support soil and agriculture, and recycled materials can be made into new products.

In addition, landfills are an anaerobic environment. This means landfills produce methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas, whereas compost is an aerobic environment. While composting’s decomposition process releases carbon dioxide, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, pound for pound, methane has an impact 28 times greater than carbon dioxide.

Plemmons said composting is preferable to landfilling as composting is a closed loop system. This means that food waste and plant products will break down and can be used again to grow new food, creating a loop, instead of sitting in a plastic-lined mound forever.

UGA’s Solution

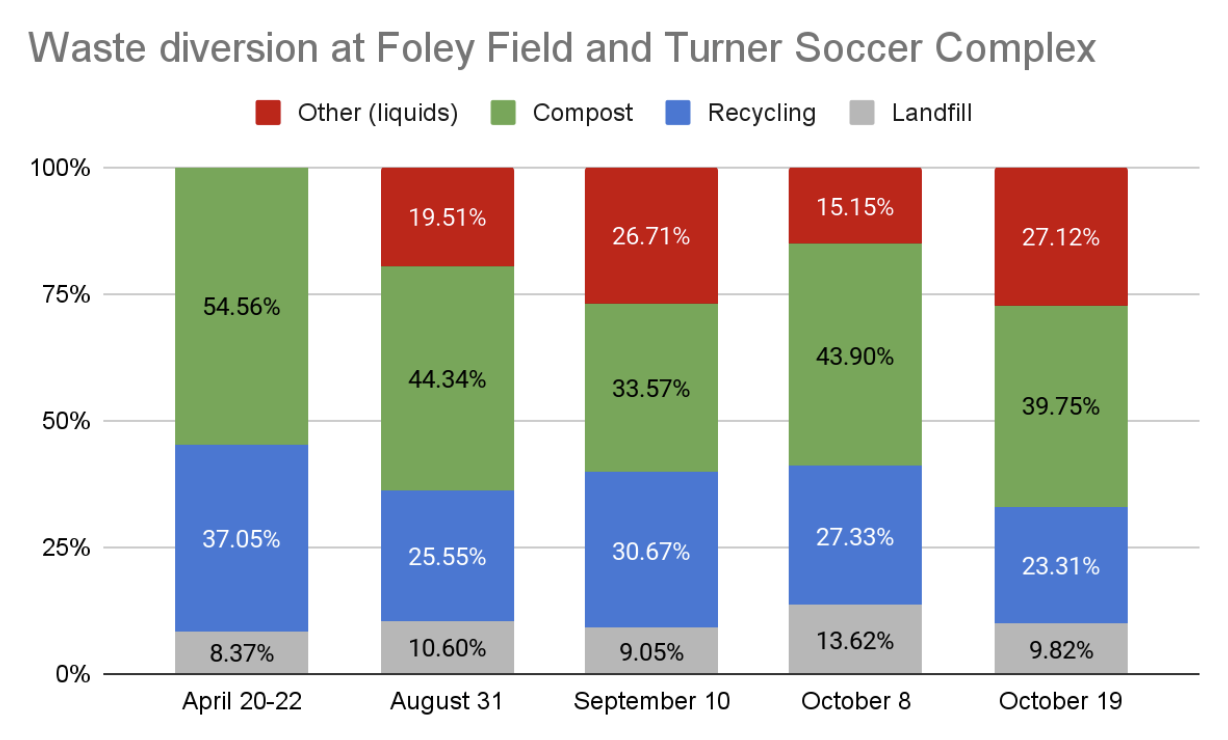

Hunter Scully, then a master student in natural resource management, saw how UGA sporting events created a multitude of waste and organized the Journey to Zero Waste Weekend at Foley Field for his sustainability certificate capstone on April 20-22, 2023. The goal of such events is to divert 90% of waste from landfills by recycling and composting. This series of three baseball games achieved diversion rates of 91.6%.

Why It’s Newsworthy: This is the first time an entire season of a UGA sport has attempted to be zero waste. Sporting events produce large amounts of trash, and the Journey to Zero Waste Soccer Season was an experiment to see how this work can be scaled up to other sports.

Scully spent the spring semester building relationships with contacts within UGA Athletics, the food service company Aramark and brands like EcoProducts to ensure that when the zero waste weekend came, most products would be recyclable or compostable. That way, hitting that 90% diversion rate goal would be within reach. Scully and his sustainability capstone group were assisted by student volunteers who educated fans on how to properly dispose of their food waste and trash.

UGA Athletics’ zero waste journey continued this fall for Georgia Soccer at the Turner Soccer Complex. The Journey to Zero Waste Soccer Season means that all home games this fall aimed to be zero waste events. With a stadium capacity of 1,682 and average fan attendance of about 1,000 people, this soccer season provided an opportunity to test how zero waste events can be implemented at UGA sports facilities.

Alexandra Molfetas, a third-year communications major, started as the Office of Sustainability’s first Zero Waste Athletics intern to coordinate these efforts. Molfetas was assisted by Tatiana Morales, a fifth-year environmental engineering major, and Brandon Barth, a fourth-year landscape architecture major. Morales and Barth are sustainability certificate students working with Zero Waste Athletics this soccer season for their capstone project, so Morales and Barth are writing a report on their progress and recommendations, which they will present at the end of the semester.

How does Zero Waste Athletics Work?

Morales and the Zero Waste Athletics team conducted four waste audits this season. The second and fourth audits revealed that about 90% of waste was diverted from the landfill, and the first and third audits were just a few percentage points under the goal.

Assistant Director of Event & Facility Operations Keenan Huss said that the first step to a successful zero waste event is investing in fan education and setting up the infrastructure. Huss and Scully coordinated with food service company Aramark to replace single-use containers, cutlery and other supplies with compostable and recyclable alternatives.

The stadium crew at the Turner Soccer Complex set up the waste receptacles of landfill, recycling and compost waste with signage about what falls under each category.

Before each game started, interns and capstone students coordinated with volunteers. Molfetas stationed volunteers at each waste receptacle to direct spectators on how to properly dispose of their waste. They also served as educators about sustainability.

Volunteers included sustainability certificate students, the Student Government Association (SGA) or anyone who signs up via the Zero Waste Athletics GivePulse.

“[Volunteering] makes me feel like I’m actually doing something good for the community,” said Mia Johnson. “We can educate the kids, which is the most important thing.”

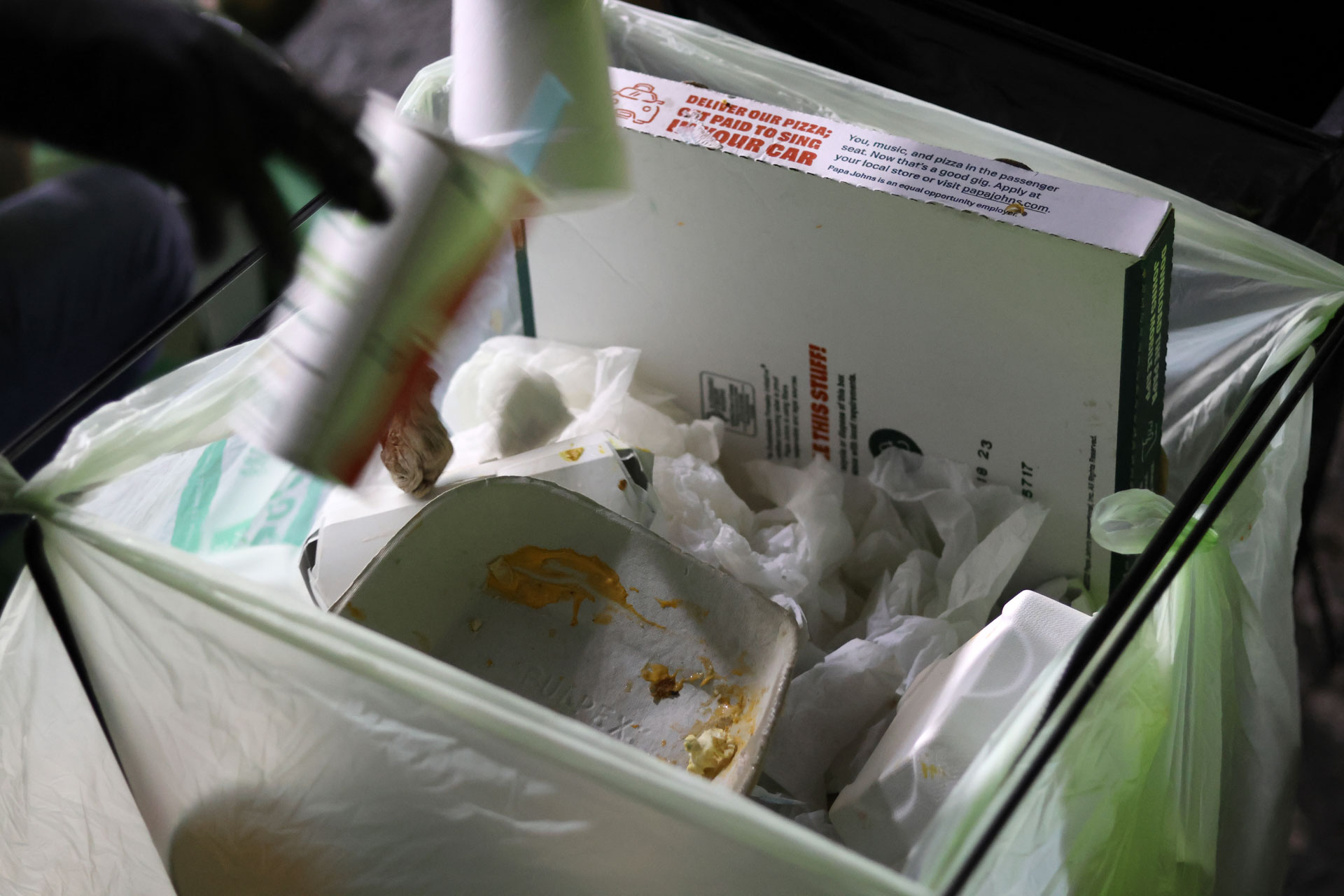

At the conclusion of the game, the stadium crew collected the bags of waste, which were color coded based on type of waste: black for landfill, clear for recycling and green for compost.

Every few home games, the Office of Sustainability conducted a waste audit to determine the diversion and contamination rates. Capstone students and volunteers weighed the bags before opening each one and sorting the contents.

After sorting, Morales recorded the post-sort weight of each type of waste. Then, the volunteers disposed of the waste in their respective dumpsters, where the Athens-Clarke County services picked up the waste.

Understanding the Data

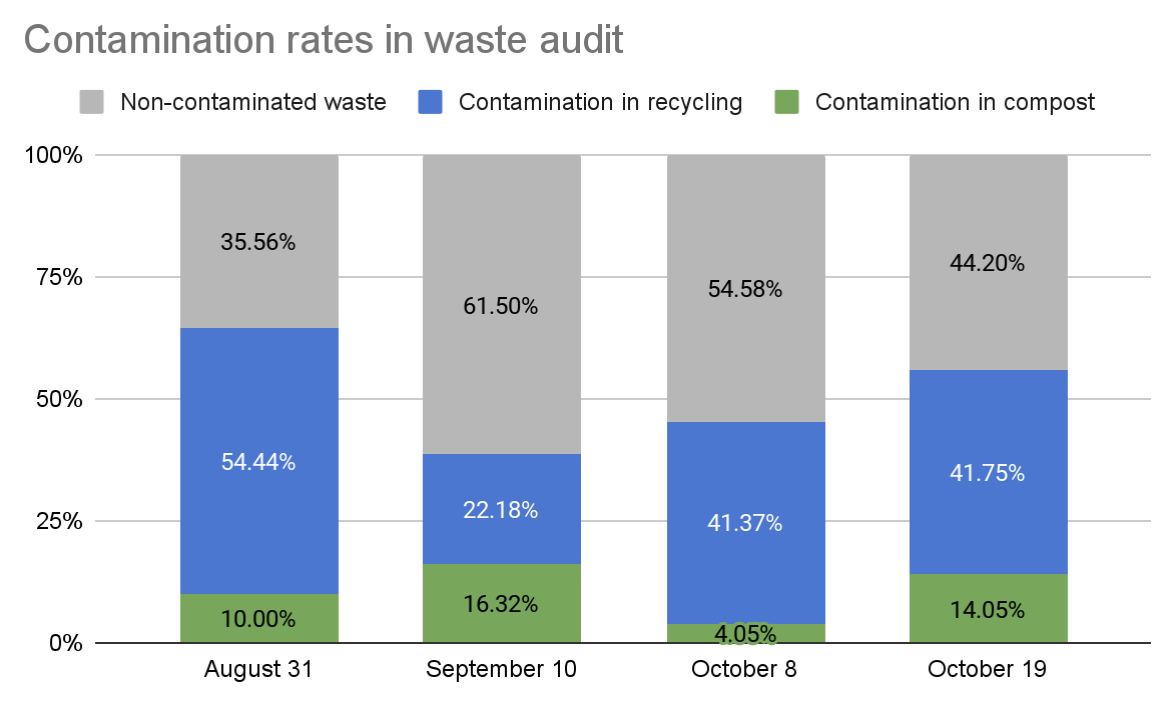

Contamination rates record how much waste was incorrectly disposed of in compost and recycling bins.

Plemmons said that with recycling contamination, too much food residue or plastic bags clog the recycling center’s sorting machines. This slows down the sorting process and devalues the material, so it can’t be sold. In some cases, an entire load can be thrown away if there is too much contamination.

Recording the contamination rates are important to gauge the effectiveness of fan education and learn how to make zero waste sporting events at UGA more effective. If contamination rates are too high, it pushes the event further away from the 90% diversion rate goal.

From game one to game two, the contamination rates went down from 64.4% to 41.9%. Morales emphasized the importance of fan education and training attendees to make the correct decision the first time when throwing away waste to reduce the need for sorting.

“It’s so much easier to just throw something away in the landfill bag and not have to ask the question: ‘Where does this go?’ and if you already knew that, it’d be easier,” Morales said, “I think education is going to be the only way to really fix the problems.”

Morales added that it’s not feasible to have volunteers at every game if Zero Waste Athletics hopes to expand their programming. By teaching fans how to dispose of their waste, less volunteers are needed to educate fans and sort the waste.

There are other factors behind the scenes that hindered the zero waste goal this season. Huss stated that due to the contracts and sponsorship deals, not every concession can be swapped for a compostable or recyclable alternative. For example, they were able to change the Coca-Cola cups to a compostable cup, but the Texas Roadhouse peanuts must be sold in plastic bags.

In an interview after the end of Georgia Soccer’s regular season, Molfetas said they had issues with spectators bringing in outside food, which often came in non-recyclable or non-compostable packaging. This added to the landfill weight at audits.

Mallie McKenzie, a midfielder for the Georgia Soccer team and graduate student earning her master’s degree in consumer analytics, would like to see more changes regarding sustainability in the locker room. McKenzie said that the team doesn’t have recycling bins. However, players take home food and catering from the stadium, preventing food waste.

“I love that our team and our facility gets to do something that’s going to benefit the environment and I think it’s a great step for athletics as a whole, and especially UGA women’s soccer,” McKenzie said.

Beyond Georgia Soccer

Other universities across the nation have made efforts to improve sustainability in athletics such as the zero waste competition for football and basketball between schools in the PAC-12 Conference.

In addition, the University of Florida has made significant efforts to promote sustainability in athletics including having the first LEED Platinum athletic facility in the country, holding the first Carbon Neutral NCAA Football Game in November 2021 and only selling concessions at the Ben Hill Griffin Stadium that are compostable or recyclable.

Huss said that the ultimate goal for UGA Athletics is for the Jack Turner Complex, which includes the Turner Soccer Complex and Jack Turner Softball Stadium, to be a zero waste venue. Director of the Interdisciplinary Sustainability Certificate Tyra Byers said that another sustainability capstone group will work on a zero waste season for Georgia Softball in the spring. Byers also said the Office of Sustainability is looking to expand to other sporting facilities at UGA.

I think there was a really great opportunity for us to lead the way and be the leaders in sustainability within the SEC,” Scully said.

Molfetas said in the upcoming seasons with Zero Waste Athletics, she wants to emphasize fan education and marketing so that spectators understand how to properly dispose of their concession waste. This way, the program can be less reliant on volunteers.

Regardless of the complications of organizing zero waste events, Molfetas acknowledged the progress Zero Waste Athletics made this season with Georgia Soccer.

“There’s lots of hurdles in the world of sustainability and it’s a slow and steady race,” Molfetas said. “The smaller steps are still large victories.”

Sophie Ralph is a senior majoring in journalism with a Sports Media Certificate in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. She also has a Sustainability Certificate, Film Studies minor and Transnational European Studies minor at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)