[Special education] is something we’re gonna stand up for… it’s not going anywhere,” said Patrick Bishop.

Patrick Bishop has worked with children since the late 1990s, first in Los Angeles as a counselor for at-risk teens. From the early 2000s until now, he’s moved back and forth from California to Georgia, working as a behavioral counselor in school districts, a youth counselor and even in foster care.

Bishop never thought he would become a teacher.

He said he never believed in the stereotypical idea of teaching solely for good test grades.

“If I go in the classroom and I’m just teaching so they can pass a test, that’s not me being truthful to who I am,” Bishop said. “It’s not going to work because they’re going to see it.”

Now, Bishop is a part of a new special education residency program in Clarke County School District (CCSD).

Threats of Dismantling DEI

The Special Education Residency Program is opening doors for instructors and teachers in CCSD, but with threats from President Donald Trump’s administration to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education and with direct threats to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs, those doors could be sealed shut.

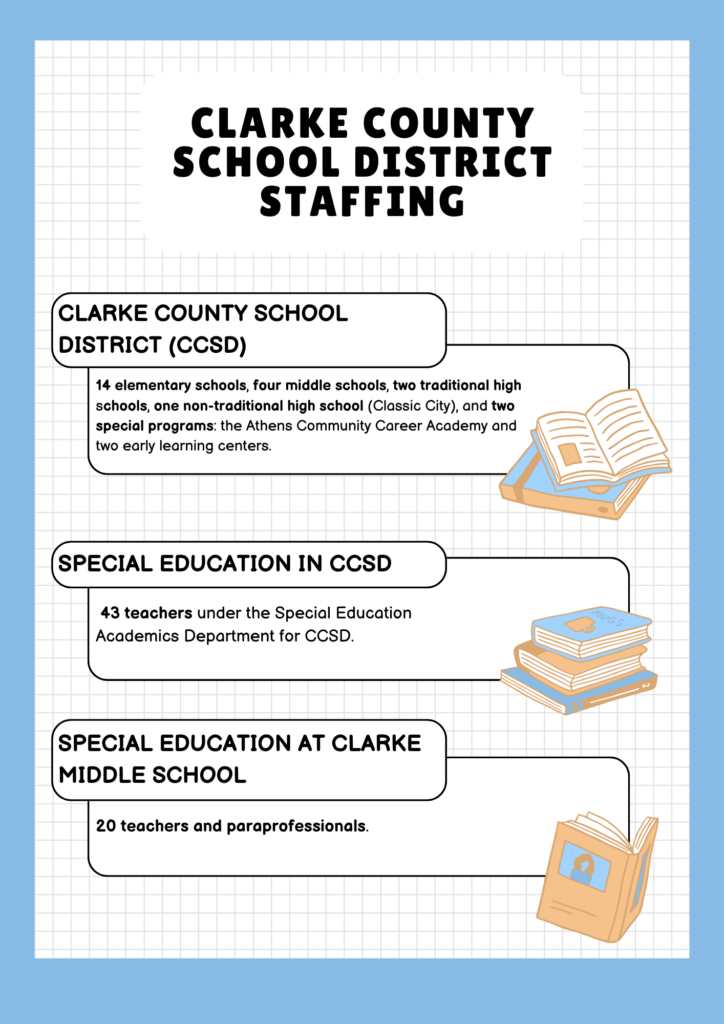

CCSD selected four employees at the beginning of January to experientially learn how to be instructors, specifically working in special education. Three of the members currently work in different elementary schools in the district, while Bishop is a paraprofessional at Clarke Middle School.

Bishop thinks special education is too important for national policy to dismantle. He is concerned about how it will be affected going forward.

“There may be kids that aren’t able to be a part of [special education] because of everything that’s going on — that might be taken out of it. That’s the thing that I think about the most,” Bishop said.

You’re taking the kids away from this that need it the most. You’re not setting them up for success.”

According to CCSD, the purpose of the program is to address a nationwide teacher shortage. Vacant special education positions specifically have been the largest barrier to CCSD being fully staffed.

After joining the program, Bishop and the other cohort members signed an agreement to teach special education for at least three years in CCSD after receiving their certification.

“I was just excited, all around, [to start the special education residency program]… these kids [in special education] like coming to school; they look forward to it,” Bishop said.

In the United States, 72% of public schools with special education teacher vacancies “experienced difficulty” filling the positions, according to the Education Department’s National Center for Education Statistics.

“A lot of people are scared, and they don’t know what they’re getting into,” said Papita Nancy Raju, a special education teacher at Clarke Middle School.

Raju has been a special education teacher for two years since moving to Georgia from Texas. The Special Education Residency Program has allowed her to show its members, like Bishop, the importance of aiding these students.

These are special kids who need special love and care.”

“The district as a whole, they are encouraging and pushing forward for more people to get this scholarship and earn this degree so that they can stay in the system and help these kids out,” Raju said.

Filling vacancies in special education is an issue not only in Athens, but across the country.

In Philadelphia, Christina Fluhr is a first-year student at St. Joseph’s University, who is majoring in elementary and special education. Fluhr works with teachers in special education, as well as teachers in classrooms who are not in special education at Samuel Gompers Elementary School as an experiential learning opportunity.

“We get to do assessments with the kids, we get to work with them one-on-one. So, I'm never really just sitting there taking notes,” Fluhr said.

Fluhr has observed that the school’s curriculum focuses on students' test scores.

“You can't walk in [to the school] without seeing posters of their test scores, their attendance… all these kids are so over-tested,” Fluhr said.

Individualized Care

In Athens, Bishop emphasizes the importance of checking in on students’ behavior. It's his gauge to see how involved the students are in school and if they can learn the class material.

“I feel like it goes hand-in-hand all the time, and there are a lot of kids around the school that aren't in these rooms that have [individualized education plans], and I run into them all day. Every single day,” Bishop said, “they start pouring out everything, and like, boom — counselor coming out.”

On a national scale, public schools must see how federal funding, and changes to diversity, equity, and inclusion will potentially affect Special Education. Fluhr says Trump’s agenda for the education system has some teachers concerned.

President Trump signed an executive order directing Education Secretary Linda McMahon to facilitate closing the agency; there is no specific timeline on initiating the closure.

“Teachers are very worried. It's a recurring thought in all the teachers' heads over here,” Fluhr said.

However, both Bishop and Raju feel as if they are the front line when it comes to defending the students they work with.

“I know how I am. I'll speak up. I'll say something. I’ve just always been that way,” Bishop said.

Mary Ryan Howarth is a journalism major at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)