In August 2021, the Athens-Clarke County Mayor and Commission approved the opening of a government-sanctioned houseless encampment behind the former North Athens School on Barber Street.

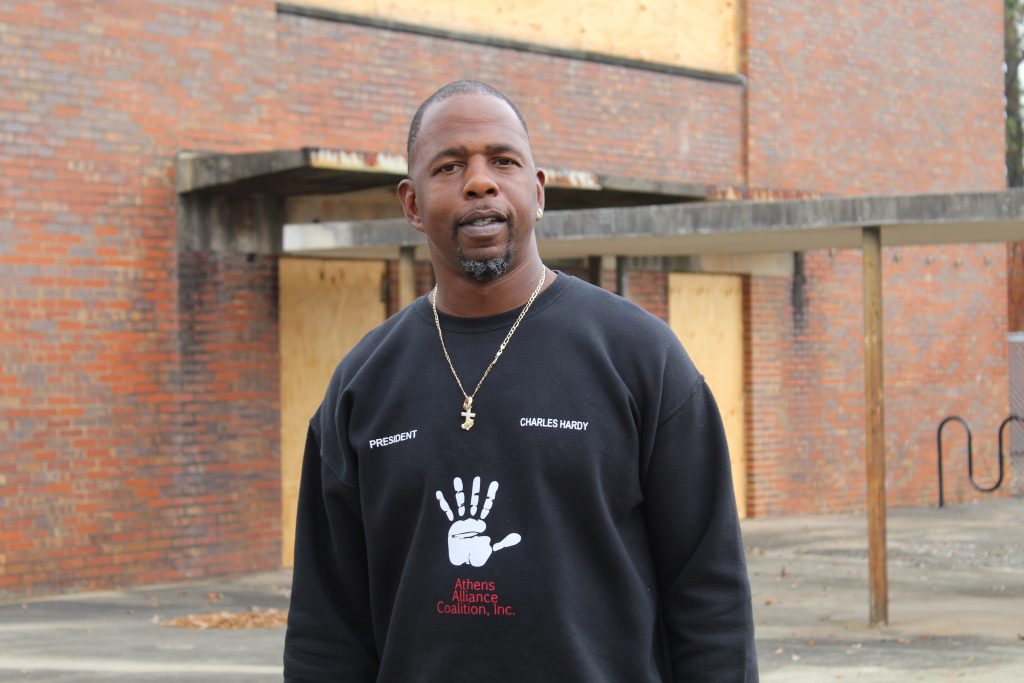

Since then, the county government has been working with the local non-profit that will serve as encampment’s operator, Athens Alliance Coalition (AAC), to create a space that will allow unhoused people to “get back into society with a good-paying job,” according to Charles Hardy, founder of AAC.

The Athens-Clarke County Mayor and Commission approved the contract with Athens Alliance Coalition on Dec 7, 2021, and the encampment will likely be ready to open by the end of the month.

Community data from Athens Homeless Coalition estimates that there are a couple hundred unhoused individuals in the county as of 2020.

Athens-Clarke County Mayor Kelly Girtz notes that over the past several months the government was receiving “requests to move people who were camping, or doing other things sort of associated with residency” on both private and public property. Compared to 2020, there has been a 64% increase in the number of incidents involving unhoused individuals reported to the police, according to the Athens-Clarke County Commission.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Athens’ unhoused residents have no legal, safe or sanitary place to set up their tents. To remedy this situation, the Athens-Clarke County government is funding a houseless encampment that will be operated by the Athens’ Alliance Coalition.

The space will be able to accommodate 50 tents, and each tent can hold several individuals. Five additional tents will also be available for emergency placement. AAC will also offer supportive services, such as counseling and financial services, to help encampment residents improve their lives.

The encampment is set to stay open for a period of 22 months, or until June 30, 2023, according to the Athens-Clarke County Commission. At that point, the government will evaluate the efficiency of the camp and decide whether to continue funding the initiative.

While Girtz and other public officials have expressed their belief that the encampment will help numerous unhoused residents, they are also exploring other ways to further assist those individuals.

“[Our goal] is to steer people toward positive life experiences after having been unsheltered, and hopefully to shorten the amount of time that people are unsheltered,” Girtz said.

Athens’ Housing Crisis: A Persistent Problem

The current housing crisis in Athens-Clarke county has resulted in “an elevated number of community members who are unsheltered,” according to the Athens-Clarke County commission. The commission also acknowledges that “for years, Athens-Clarke County has been a community that has experienced a sizable homeless population.”

The number of unhoused individuals in Athens-Clarke County has ranged between 210 and 239 in the past five years, according to the Athens Homeless Coalition’s community data. In 2020, at least 210 Athens residents were identified as unhoused.

Athens-Clarke County is considered a continuum of care by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Renewal, meaning that the county receives funds to assist the unhoused population. As a result, they are required to “conduct an annual count of homeless persons who are sheltered in emergency shelters, transitional housing and safe havens on a single night as well as those living in places not meant for human habitation,” according to the Athens Homeless Coalition.

To collect this data, Athens-Clarke County’s Housing and Community Development department partners with several organizations in the county to conduct a “point-in-time” count on a single night in January. These staffers and volunteers collect a variety of data on Athens’ unhoused population, including their gender, age and barriers to housing.

The point-in-time count shows that the majority of unhoused residents are adult males, who can experience greater difficulty in finding resources to get out of homelessness. According to Athens-Clarke County’s Manager, Blaine Williams, many county organizations working to assist unhoused residents have limited resources and are often forced to prioritize those deemed most vulnerable, usually women and children.

When unhoused residents are unable to gain access to shelters or other assistance programs, they are forced to set up camp where they can.

Currently, when unhoused people camp on private property, the police are legally required to remove them from the premises. Prior to the establishment of the encampment, however, there was nowhere else for them to go.

Given this lack of alternative options and the input of various organizations, the Athens-Clarke County government is creating the encampment as a low-barrier entry space. As a result, this encampment’s location was chosen to be far away from any schools to allow houseless sex offenders. In turn, no children will be allowed to stay in the encampment.

Creating a low-barrier entry space has been influential throughout the process of setting up the encampment.

Setting Up the Encampment

To establish the encampment, the Athens-Clarke County government has had to identify a location and operator.

Since the encampment is intended to allow anyone to reside there, including sex offenders, the government was very intentional in selecting a location that would be far away from any schools or other areas with children, Williams said.

Zoom into the map to see where the encampment is in comparison to Athens landmarks.

The commission ultimately decided on setting up the encampment behind the former North Athens School, next to the Pilgrim’s Pride De-Bone poultry factory. The school has laid vacant for several decades, and the county bought the property for $400,000 in December 2017.

The encampment’s location is a 30-minute walk, or approximately 5-minute drive, from the two most prominent homeless encampments, Cooterville adjacent to the CSX railroad tracks at North Avenue and Willow Street, and another encampment at the North Oconee River Park (west), according to the Athens-Clarke County Commission.

After approving the location, the government’s facilities team secured the building by boarding up doors and windows to ensure that there would be no safety hazards for anyone inside the encampment.

In addition to deciding on the location, the Athens-Clarke County government also had to decide on an operator.

In the resolution establishing the encampment, the commission states that they will not be the ones running the encampment and, instead, will identify a “qualified nonprofit agency(ies) to assist ACCUG [Athens-Clarke County Unified Government] with the development and operation of a sanctioned encampment.”

The county called for proposals from local organizations with experience providing services to the unsheltered community.

The nonprofit agency that was chosen was Athens Alliance Coalition (AAC).

Athens-Clarke County chose to involve AAC because of the organization’s experience and specially-trained staff, according to Mayor Girtz.

“We wanted folks who already have relationships with individuals on the street and who already have staff mobilized for similar activities, to be able to participate in the homeless encampment,” Girtz said.

Since its founding in 2017, AAC has offered a variety of services for unhoused people including counseling, education support, mentorship and financial services. The organization’s goal is to provide opportunities for all individuals in the Athens community.

AAC members and volunteers frequently visit various locations throughout Athens to help clean areas where unhoused people live, offer transportation to appointments and interviews, and deliver food and supplies to those in need. A full list of services they offer can be found on their website.

AAC will continue to serve both those who choose to move into the encampment, as well as unsheltered individuals throughout the rest of the city.

To be able to oversee the encampment, AAC signed a contract with the Athens-Clarke County government. County Manager Williams helped craft the contract that was approved 8-1 on December 7, with District Commissioner Mike Hamby as the sole opposing vote.

Since the issue of houselessness requires a multifaceted approach from the Athens-Clarke County government, ranging from sanitation to police, Williams has been supporting numerous county department directors while also adhering to the direction of the commission.

Through various meetings with AAC, Williams and other county officials have helped the organization overcome two “steep learning curves” that need to be addressed to ensure the encampment’s success. The first is understanding what running an encampment will entail. The second is reviewing the responsibilities involved with receiving federal funds.

Williams said that the government’s guiding principle throughout this process has been to “make things better than it is now.”

Currently, unhoused individuals constantly face the potential of being forced to relocate and lack access to bathrooms, regular garbage disposal and the potential of having their belongings taken.

This situation has translated to the government focusing on security, safety, sanitation and support.

The Athens-Clarke County government has been looking at this initiative as having two phases, with the first 12 months consisting of Phase 1 dedicated to security, safety and sanitation and the second phase dedicated to advanced supportive services.

The encampment will not just be a legal, safe, and sanitary place for unsheltered people to camp, but will also provide supportive services.

“The AAC was interested in taking this on because of our ability to provide counseling, transportation to job interviews, help with paperwork and clean facilities,” Hardy said.

The government has been working with AAC to develop a model they can use to partner with other organizations and help support unhoused individuals in finding housing and employment.

Providing supportive services is crucial because “the homeless encampment is not the endgame, it’s just a waypoint on the way up,” Williams said.

Mayor Girtz noted a similar desire to create a long-term plan.

“Part of what we’re doing in conjunction with this array of homeless providers is developing a long-range plan,” Girtz said.

He said the plan will work on a “multi year-continuum” and should address houselessness, addiction, behavioral health needs, the need for permanent supportive housing and workforce development activity for people who’ve been unsheltered.

Inside the Encampment

Since the commission approved the establishment of the encampment, the county has installed electrical outlets, set up sanitation features and cleared the area.

Click on an image to enlarge and read full captions.

The space is wheelchair accessible and will offer outdoor water facilities, water spigets, eight porta-potties, lockers, bike racks, 55 “state of the art” tents, WiFi, electricity, garbage disposal, an outdoor kitchen, daily meals and a picnic area. The encampment will also include a container with clothing donations.

AAC plans to use their 15-passenger van to transport individuals staying in the encampment to Bigger Vision of Athens on North Avenue for daily showers and laundry. The van will also transport residents to doctor’s appointments, grocery stores and more.

The encampment aims to provide a safe space for unhoused people in Athens to live and get support while working on getting into permanent housing, said Hardy. AAC will be providing encampment security personnel and also keeping track of who enters and exits the premises. Security cameras will also be installed throughout the encampment.

“We will have security, but safety isn’t foreseen to be a big issue,” Hardy said.

According to Hardy, while the encampment has limited capacity, they intend to help individuals move into more permanent housing to open spots for new encampment residents.

“If you’re [experiencing] homelessness, you’ve got a shot,” he said.

Since the Athens-Clarke County government intends for the encampment to be a low-entry barrier living space, there will be no requirements in place in order to live there.

Hardy said that the AAC will be maintaining a spreadsheet of all of the encampment residents in order to measure how successful the program is at helping people get on their feet.

Residents will be allowed to stay as long as they feel necessary and will be able to receive continued support after leaving the encampment.

A Model for Success

Legal homeless encampments may be new to Athens-Clarke County, but they have been set up in cities all over the country from Seattle to Portland to Honolulu. In Georgia, Shinnah Haven, a legal homeless encampment in Douglas County, has helped inform some policies and procedures for Athens-Clarke County’s encampment.

In 2017, a tropical storm forced many unhoused residents of an encampment in Douglas County to leave their belongings and seek refuge in motels or friends’ housing. After the storm cleared, the owners of the property where the encampment was located began bulldozing through residents’ tents, giving no opportunity for its residents to collect their belongings.

This motivated Charles Branson, Vice Chairman of The Board at Douglas County Homeless Coalition, to contact County Judge William Beau McClain to set up a location where unhoused residents could legally set up tents.

In September 2017, a plot of county property was designated for the encampment. The encampment affords limited electricity, portable restrooms, trash service, water access and access to donated food and mental health care.

Since July 2019, the encampment has had 161 residents at the camp, said Branson. The average age of residents is 42 and the average stay lasts 21 days. The longest a current resident has stayed at the encampment is 312 days.

Over the past four years, the encampment has evolved in a variety of ways to accommodate for various challenges. For example, while the encampment started as co-ed, several conflicts resulted in the encampment being male-only, said Branson.

The county is currently working on a separate initiative that would provide housing for homeless women called Sanctuary Village, a “personal vision” of Judge McClain, which involves five former classroom trailers converted to one-bedroom apartments, fully furnished.

Over the years, they have also developed over three pages of rules, which detail how the community should operate and what actions will result in eviction, said Branson.

According to the “Rules for Shinnah Community” document provided by Branson, possession of a gun or weapon or usage of drugs or alcohol on the property, for example, result in eviction from the first offense. Getting into fights or failing to maintain a clean area results in eviction upon the third warning.

Eviction decisions are made by three volunteers, led by Leila Myers, said Branson. Making these decisions can be difficult, especially when they know the underlying cause is mental illness.

“We try to be consistent in enforcing rules, but there are some things where they get three chances and then we talk ourselves into giving them another and another, and other times where we have hard rules,” said Branson.

The long-term goal of the encampment is to provide people with the ability to acquire housing.

“The definition of chronic homelessness is someone who is living in conditions unfit for human habitation,” Branson. “I would say that in the long term, living inside a tent is living in a situation unfit for human habitation.”

Branson went on to explain that “the only permanent solution for homelessness is a source of income.” The encampment partners with other organizations and local businesses to try to provide employment opportunities.

As of November 2021, 11 of the 21 Shinnah Haven residents were employed. Despite being employed, these residents still have difficulty finding housing.

“Homelessness isn’t a pond you can dip all the water out of, it’s a river,” Branson said, reflecting on his years of work with unhoused individuals. “You have to realize that it is real people going through real situations and you have to work with compassion.”

Evaluating Success and Addressing Homelessness

The commissions’ resolution approved the establishment of the encampment for 23 months and will decide whether to continue the encampment after reassessing its success. Though the government thinks the encampment will be an important step to addressing homelessness, they are also considering other strategies.

“This is going to be data-driven,” Williams said. The type of data that the government is interested in includes how many people are entering and leaving the encampment, whether individuals are transitioning to another encampment, housing or recovery program and the percentage of residents that are utilizing supportive services.

Since the encampment is temporary, however, the county government is also looking for longer-term solutions for unsheltered individuals.

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the national shortage of affordable housing, which has brought new challenges for local governments that are trying to reduce homelessness.

“Homelessness is at least partly connected to rising housing costs and the challenge to find housing, so one area where I anticipate we’re going to be collaborating with some partners is providing transitional housing,” Girtz said.

Investing in transitional housing requires local governments to purchase more units and construction services in order to serve those with more permanent needs, like the elderly or disabled.

In addition to addressing housing needs, Girtz also said that strong case-by-case management is an effective way to help the unsheltered community.

“Connecting with every unsheltered individual to find out their particular challenges, whether they’re a veteran with PTSD or somebody with an addiction that needs to be managed, is part of successful individual case management.”

In the meantime, AAC will continue to provide counselors, transportation, and job opportunities for unsheltered people in the encampment to find permanent work opportunities.

Moving Forward

The site of the Athens encampment will remain empty until improvements are finished.

Hardy, despite residing outside of Athens, monitors the encampment’s progress at the site every day. He’s hopeful that he’ll be able to move people in by the end of December.

Hardy said that priority will be given to unhoused individuals camping in Cooterville by the CSX railroad, as CSX has made clear that they will be removing the camp as soon as they can.

Hardy also remains confident in the community’s ability to ensure the encampment succeeds.

“[Anyone] will be welcome to come over here and volunteer,” he said. “We’re gonna need all the volunteers we can get.”

People can volunteer at the encampment and can sign up by calling 706-612-4556, emailing athensalliancecoalitionllc@gmail.com or through the “Contact Us” section on their website at https://alliancecoalitionllc.com/.

“We’re all excited because now we can do this legally. And … that is great man and to get the city officials on board with it,” Hardy said. “That’s even more exciting.”

Alaina O’Regan, Aleeza Rasheed, Anna Rayford and Mennah Abdelwahab are senior journalism students at the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)