The Full Plate program delivered approximately 161,562 pounds of food to agencies in need in 2017, and they are on track to deliver more than 200,000 pounds in 2018.

These estimates come from ACTION, Inc., the parent nonprofit organization that began Full Plate. The program was started because “someone’s basic needs for food and shelter must be met first,” said Brenda Dove, the senior director for human resources and fund development at ACTION, Inc.

Why It’s Newsworthy: There is an ongoing national trend of restaurants increasing the amount of food they throw away, and the main reason cited by restaurants nationally for not donating the food is because of transportation constraints. Full Plate bridges the gap between restaurants with food waste and organizations in need of quality food.

To help meet people’s basic needs, the two full-time employees working for the Full Plate program drive from restaurants and other businesses that donate food, to places in need of food to serve, such as the Salvation Army and Project Safe.

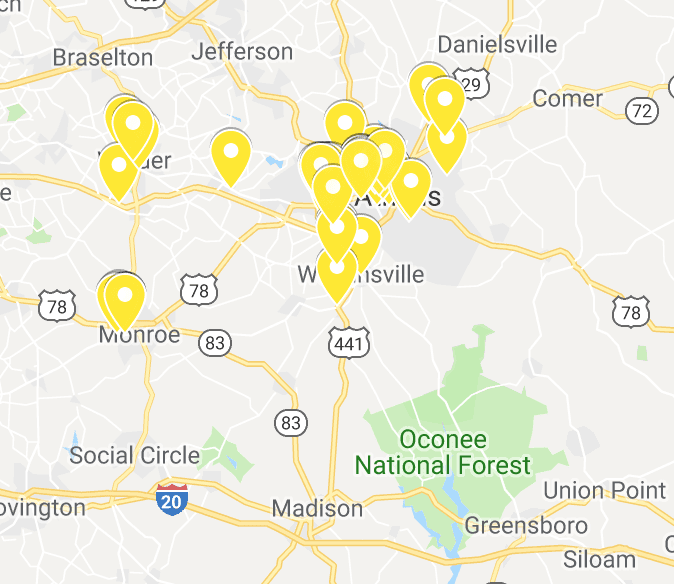

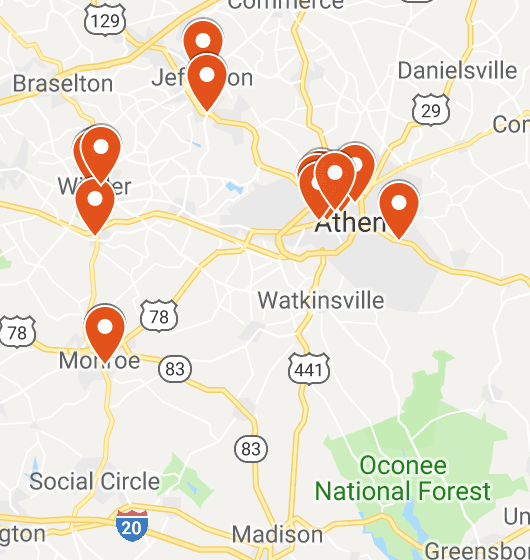

The drivers take two routes. One goes throughout Clarke County and the other is what the drivers call “the rural route,” including Barrow County, Walton County, Jackson County and the recent expansion into Oconee County.

According to Full Plate program manager Stacey Favors, he and the other full-time Full Plate employees drive an average of 50 to 70 miles per day on their Clarke County route alone. This route is completed at least five days a week.

Along their routes, Favors estimates they pick up about 2,000 to 3,000 pounds of food weekly.

“It helps a lot of people in the community. We actually serve between 600 and 800 people on a daily basis,” added Favors.

Why is a Food Rescue Program Needed in Athens?

Before expanding into other counties, The Full Plate program started in Athens-Clarke County in 1987.

ACTION, Inc. discovered the need for a food rescue program like Full Plate through a combination of research on the population of Athens, and observations of the amount of waste restaurants produce.

“The poverty rate in Athens-Clarke County is tremendously high, and there are a tremendous number of families that are hungry or food insecure, so we felt the best way was to partner with businesses and restaurants that have food that would otherwise be thrown away and to rapidly deliver that food to organizations so that they could in turn use that food to feed individuals in need,” Dove explained.

According to 2016 data from County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 21.4 percent of people in Clarke County have limited access to healthy foods. This percentage far exceeds what is reported for neighboring counties.

The amount of restaurants in Athens, along with the University of Georgia’s food services, presented an opportunity for Full Plate founders.

Based on data collected by the Food Waste Reduction Alliance, over a period of two years the percentage of food waste in pounds from restaurants in the United States rose from 84.3 percent to 93.7 percent.

The Food Waste Reduction Alliance also found restaurants reported that the biggest barrier for donating food waste was transportation constraints.

Full Plate was created to fill the gap in these persisting trends.

We’re reducing hunger and food insecurity while saving our partnership organizations money. Helping them save on their budgets, so they can direct those funds into other essential services, and we are also tremendously reducing the food that would otherwise be thrown in landfills,” Dove explained.

What is the Impact?

Full Plate delivers excess food from restaurants to what Dove calls the, “most vulnerable populations,” for example, battered women and children, people in alcohol and drug recovery programs, the elderly, at-risk youth and people in homelessness.

Donors and delivery sites are divided into two categories: weekly and on-call. Weekly donors and delivery sites are visited by Full Plate drivers three to fives times each week. On-call donor and delivery sites reach out to Full Plate when they have a surplus or a substantial need for food.

The Georgia Center is one of Full Plate’s weekly donors.

“It’s helping us with sustainability and allowing us to give back to the community. It’s hard to see things go in the trash, but at the end of the day, we generally just don’t have a use for it,” stated Rob Harrison, executive chef at the Georgia Center.

Favors estimates that 70 percent of food Full Plate receives comes from the University of Georgia dining halls and other on-campus restaurant sites.

The food donated by the Georgia Center is rapidly transported to delivery sites like Cornerstone Church. Cornerstone has been partners with Full Plate longer than Care and Connections Pastor Steve Stringham can remember.

As a weekly delivery site, volunteers at Cornerstone Church feed more than 150 people every Sunday and host a food pantry every other weekend to provide people access to products like fresh produce.

Cornerstone Church’s operation has shifted since their partnership with Full Plate. They started by feeding 10 to 20 people in a week, and volunteers cooked the dishes themselves. Now feeding more than 150 people each week, Stringham said, “We wouldn’t have been able to deal with the enormity of how we do it now without all the food that we get from Full Plate.”

Favors explained the difference that the food he delivers can make for organizations: “In some agencies, we provide close to 65 to 75 percent of their food to them. That can help them save money so they can provide more services to their clients.“

Getting food from donors to delivery sites is not as simple as pick-up and drop-off. Certification is required on all sides to ensure that the food is handled properly.

Every five years, Full Plate employees must attend classes and pass an exam to demonstrate their understanding of food safety, and receive food safety certification. At least one person at delivery sites must also be food safety certified.

Further protection for donors and Full Plate comes from The Federal Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act. This act protects donors from liability when donating food to a nonprofit organization, such as during the E. coli outbreak linked to romaine lettuce earlier this year.

ACTION, Inc. staff believes that part of the reason they sometimes have trouble convincing restaurants to partner with them is because restaurant employees do not know that they are protected from liability under the Good Samaritan Act.

Full Plate employees take further precautions regarding food safety by immediately throwing away food that has a chance of being unsafe once they receive word of food health outbreaks from the federal government.

Favors also keeps detailed invoices, so he can track where certain food items came from in case he needs to contact restaurants about the safety of the food.

“Food safety is our number one concern,” Favors said.

Plans for Expansion

Full Plate just expanded into a fifth county, and the goal is to continue growing into areas of need.

“We don’t want to stop here, we want to expand it further into additional counties because the need is there,” Dove stated.

Moving forward, Dove and Favors both see room for improvement in public relations initiatives and funding.

Right now, Full Plate receives funding from federal and state grants, foundations, corporate sponsorships, corporate grants fundraising, individual donations and the United Way of Northeast Georgia.

Favors finds it difficult to pick-up and deliver food on his routes and fundraise for his program at the same time. He has created a new fundraising plan that he hopes will become a new source of money for Full Plate.

“Hopefully I can partner with sororities and fraternities on University Georgia’s campus that fundraise, but have the money directed to this program,” Favors said.

Full Plate also has goals beyond raising more money. Dove explained that the number of Full Plate food donors has grown exponentially, and she wants that to continue.

Dove’s goal for reaching more potential food donors is hosting a presentation for a restaurant association so a large group of influential people have a clear understanding of the Full Plate program.

Dove is used to being persistent when trying to increase the amount of Full Plate donors.

“Some restaurants are afraid to donate food because it’s not anything they’ve done before, but we do not give up,” she said.

Alexandra Travis is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.