It’s easy to make mistakes. It’s easy to falter under the weight of a wrong decision, and it’s easy to become burdened by the missed opportunities and the failures. In those moments, getting a second chance matters most, but if you’re an inmate, who has already been rebuked by society, locked away and tormented by past decisions, getting a second chance after being released seems impossible.

“I don’t look at anybody as an inmate. They’re human beings just like my deputies, my records clerk, my mom, my sister [are] — everybody is,” Athens-Clarke County Sheriff John Q. Williams said. “We need to have that approach of understanding that human beings do things. They make mistakes … so we got to start looking at people as people.”

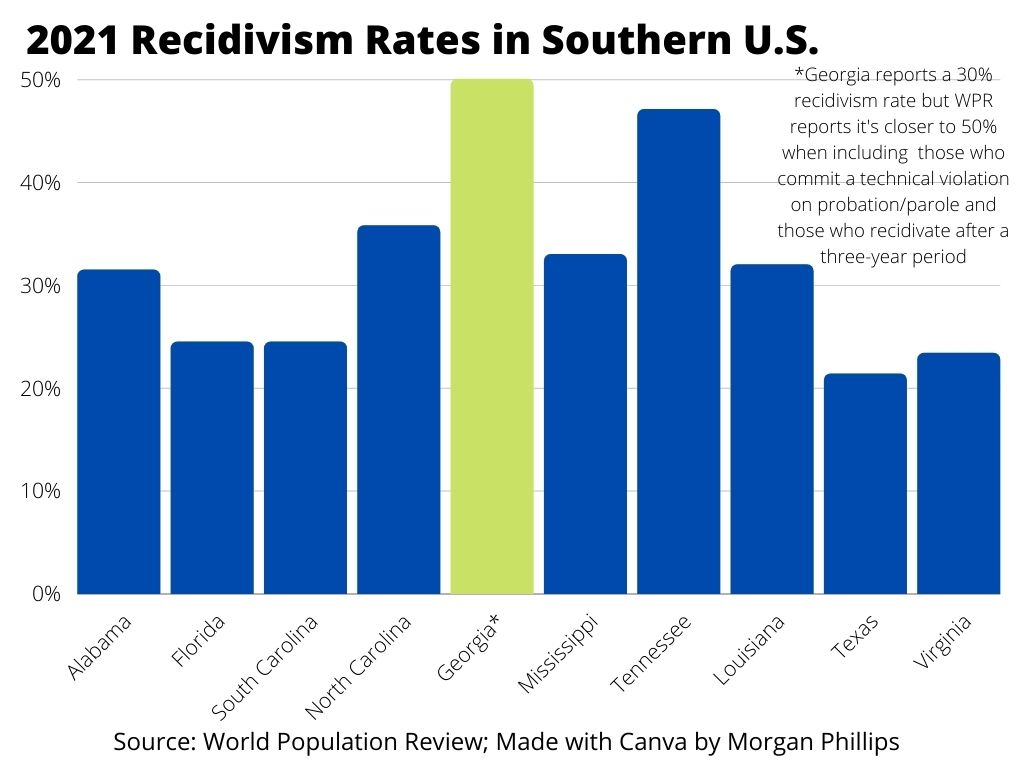

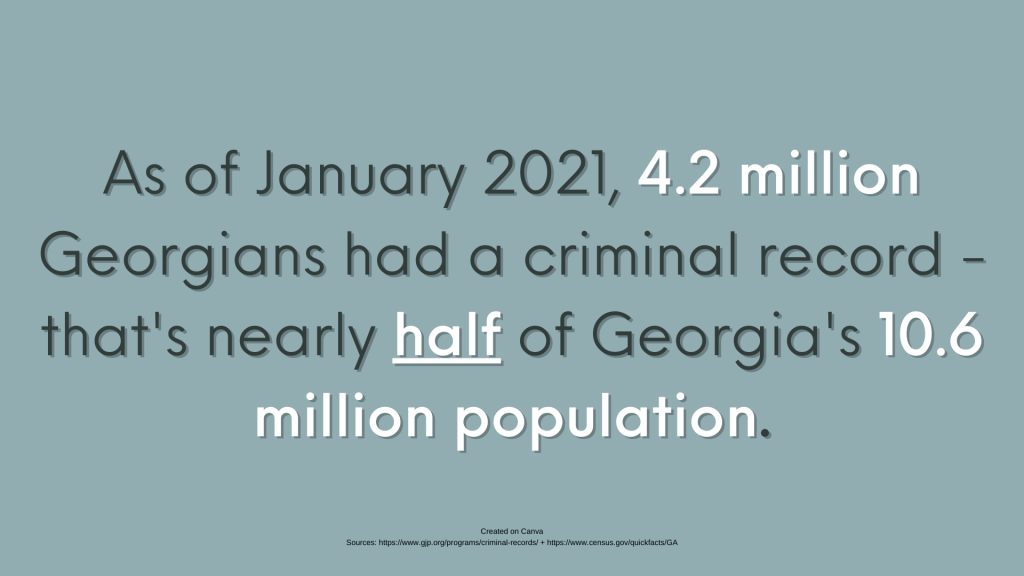

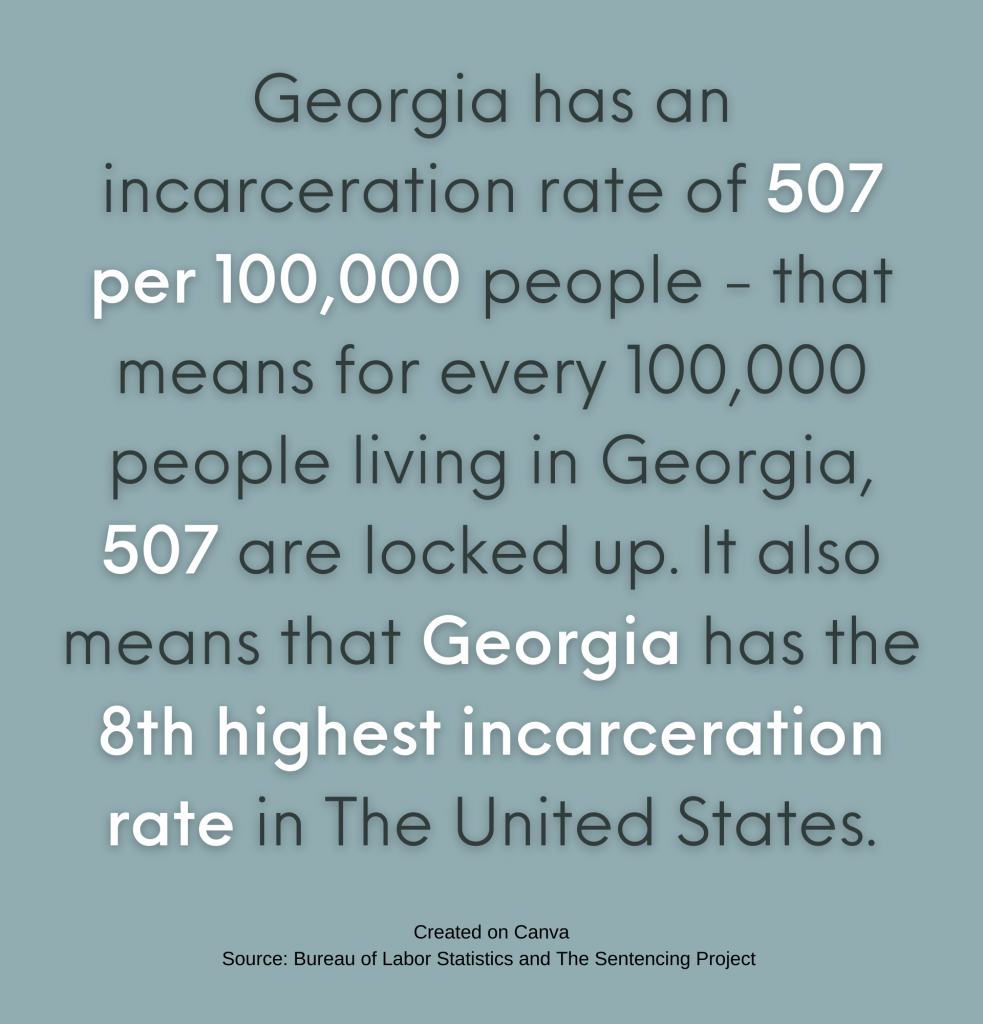

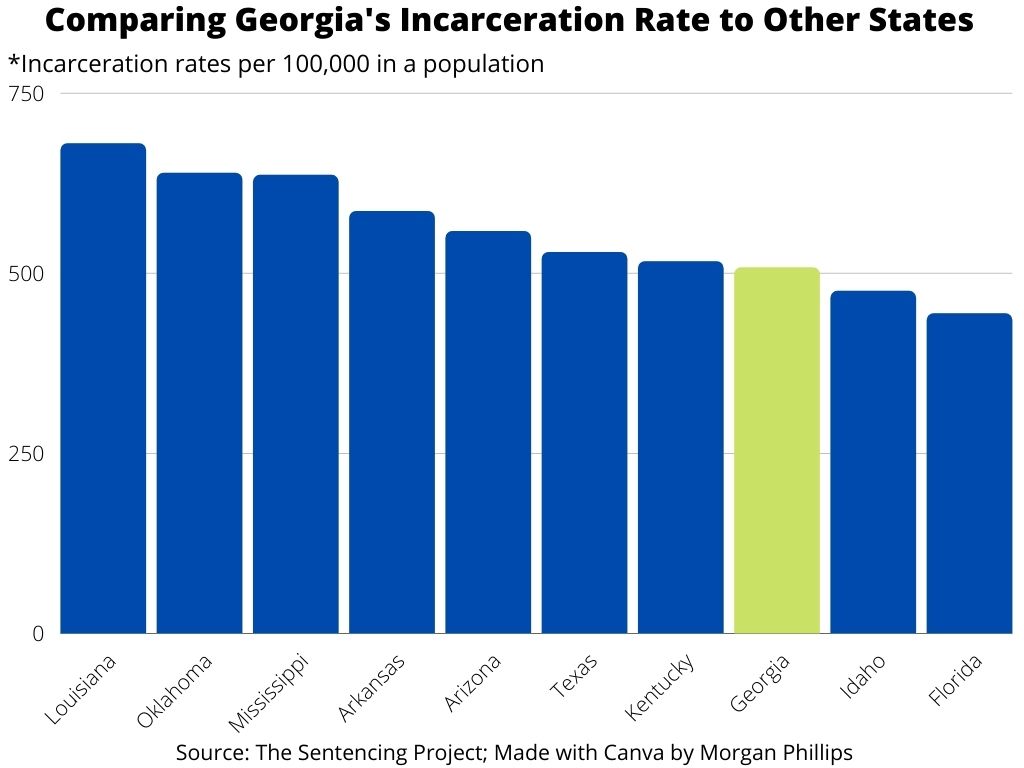

In Georgia, nearly half of released inmates end up reoffending and going back to jail. Georgia’s recidivism rate is slightly higher than most states. Thirty-five states have a recidivism rate below 50%, while five states have the same recidivism rate as Georgia. Delaware has the highest recidivism rate at 64.5% while Oklahoma has the lowest rate at 20.1%, according to World Population Review.

But, Athens-Clarke County has implemented several second chance programs to help reduce Georgia’s recidivism rate and to help inmates overcome the obstacles they face as they re-enter a society that has moved on without them.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The cost of crime is expensive. In 2019, housing one offender in a Georgia prison for one year cost over $24,000. But, assimilating inmates back into society can save taxpayer dollars and put money back into the state. A 2011 study by the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia found that obtaining jobs for just 100 former inmates would create $47,800 in annual city wage tax revenues and $1.9 million total post-release wage tax contributions over the employees lifetimes. Second chance programs, by attempting to prevent inmates from reoffending, can also help keep communities safe from crime.

Barriers to Re-Entry

Once they are on the outside, released inmates have difficulties finding jobs because they are stigmatized or banned from certain jobs because of their criminal records. They have a hard time finding housing because of their record, and many find it difficult to adjust to their new life, especially if they have a mental illness or other disorder. Oftentimes, failures to integrate back into society cause inmates to end up back in jail.

The inmates at Athens-Clarke County Jail face similar obstacles, according to Donikia Gray, program coordinator at the ACC Sheriff’s Office.

Mark Pulliam, ACC chief probation officer, sees these issues on the probation side as well.

To help with these issues inmates are facing out in society, Athens-Clarke County has implemented a program that deals with the mental health of inmates.

Dealing with Mental Health

According to the American Psychological Association, the rates of mental illness are three to four times higher in prisons and four to six times higher in jails than in the general population. Katie McFarland, a licensed clinical social worker who works with the Athens-Clarke County Police Department, has seen similar trends in the county jail.

McFarland said a study conducted in the Athens-Clarke County Jail showed that between 38% and 39% of the population had some sort of behavioral health diagnosis, a mental illness, or a co-occurring substance use disorder. The same study reported that 53% of those individuals with mental illness or co-occurring disorders went back to jail within a year.

“When they are released from jail, connecting them back to services and treatment, and support is very important so that we don’t have this continuous cycle,” McFarland said.

The ACC Police Department has a co-responder program where law enforcement and mental health professionals respond to calls together to help divert mental health issues when possible.

McFarland said this program is limited in its success when inmates cannot find housing.

“Housing kind of makes or breaks things,” McFarland said. “For a lot of people, it’s hard to get them into treatment. It’s hard to get them to take medication and to follow healthy living type things and go to appointments when they don’t know where they’re sleeping tonight or they’re sleeping under a bridge or in a tent.”

According to a 2018 report by Prison Policy Initiative, formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.

Finding Employment: Ban the Box and Expungement

In 2004, the Ban the Box Campaign started, and it advocated for employers to remove the box on job applications that asked about criminal history. Georgia became a ban the box state in 2015. The law removed questions about criminal history from the original job application for state employees and postponed the background check until the interview stage.

Research shows that while some groups have been helped by ban the box laws, Black men, even those without a criminal history, are less likely to get called back or hired after a ban the box law is put into place. Researchers said this could be because when employers cannot ask about an applicant’s criminal history, they assume young Black men have records and weed them out.

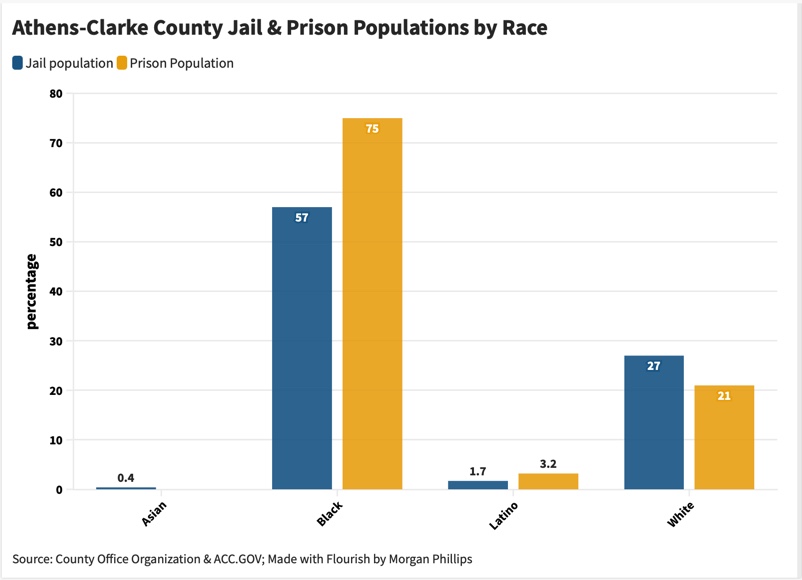

In Athens-Clarke County, African Americans make up the majority of both the prison and jail populations. Though African Americans make up 29.2% of ACC’s population, they make up 57% of ACC Jail’s population and 75% of ACC Prison’s population.

Because Georgia’s ban the box law applies to state positions only, Athens-Clarke County helps inmates with employment by organizing expungement events. Inmates can sign up, get their criminal histories reviewed and get advice from lawyers about what can be expunged from their records.

“When people have access to good jobs [and] to opportunities — that helps make the community safer. Someone who is prevented from getting a job because they were arrested 10 years ago, even when the case was dismissed, doesn’t help the community in any way. It certainly doesn’t help that individual,” said William Fleenor, chief assistant solicitor for ACC.

Since starting the expungement events in 2017, Fleenor said they’ve reviewed 412 applications.

Athens-Clarke County Sheriff John Q. Williams sees the potential in these expungement events.

“It’s not like you can just decide to be Jessie James and go robbing banks 10, 11, or 12 times … It’s a one-time thing and its specific types and cases that you can get [expunged]. But it’s there and it helps, so if you really want to turn your life around … it gets your foot in the door,” Williams said.

But Williams said there is a middle ground to be had in the discussion on banning the box.

Finding Employment: Programs Inside the Jail

Athens-Clarke County has been working on programs available to inmates to help them obtain jobs when they get out. One of these is the “Welding to Work” program, which is a partnership between ACC Corrections Department and Athens Technical College. It’s a four-week program that teaches inmates welding and work skills.

Mark Pulliam said his offices have a list of “second chance employers” willing to hire inmates.

“The first thing on a job application is usually criminal history,” Pulliam said. “Well, we want to know ahead of time, what are [the employer’s] disqualifiers? Do you have a disqualifier for any criminal offense? Do you have a qualifier just for a violent offense? … So we know when the probationer gets here what’s a good fit for this person.”

Donikia Gray said inmates have had success in getting jobs at Goodwill, Caterpillar and local poultry plants.

The ACC Jail also helps inmates get their GED to further their ability to get a job after jail.

“That helps once they get on the outside because they can help their family and hold their head up high because they have something — they have a job, they have a skillset as opposed to just going back to exactly what they might have been doing before that got them in jail in the first place,” Sheriff Williams said.

Finding Structure Outside the Prison Walls

An issue some inmates deal with after leaving jail is that the structure and routines they had in jail no longer exist.

Gray said most of the inmates at ACC Jail find structure through rehab or addiction services after being released.

Another option is Athens-Clarke County’s Accountability Courts, which include a DUI/Drug Court, Veterans Court, and Treatment and Accountability Court.

“We’re really embracing treatment courts. The idea of treatment courts is that rather than punish someone and lock them up and hope that teaches them a lesson, we’re actually trying to get people into treatment,” Fleenor said.

Fleenor said treatment courts are effective at reducing recidivism rates because it gives people treatment while also holding them accountable.

Pulliam has seen firsthand the success of the treatment courts.

“A lot of times, it’s not that the person is bad, that the person is a criminal; it’s that the person had a life-changing experience that threw him over the edge and he didn’t know how to cope with it, and so a lot of these accountability courts help them get the tools to cope, and that’s exciting to see,” Pulliam said.

But, Gray wishes the county could do more to help inmates find structure when they leave.

“I wish we could have at least a 30-day period where they get the structure before we actually release them into society,” Gray said. “Because here it’s structured. Out there, you get angry or upset and you have things you can do that will land you right back in jail.”

Saying Goodbye and Letting Go

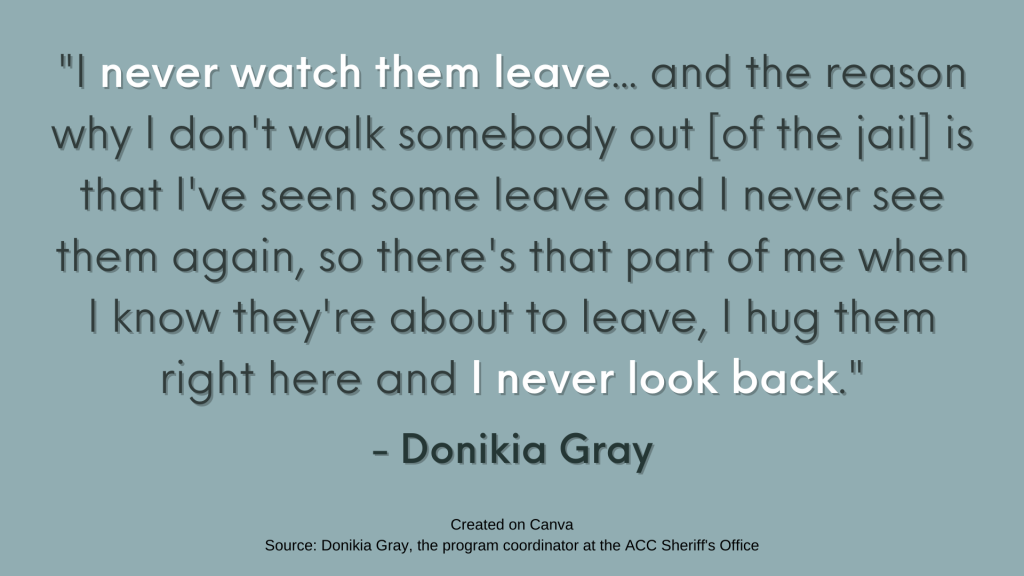

For the officers, the coordinators and the clinicians, it’s hard seeing inmates walk out the jail doors because there is no guarantee what will happen.

But, Gray said for the released inmates to succeed, it will take a village.

“I would like Athens-Clarke County to know that we do believe in second chances, [but] the Clarke County Sheriff’s Office and law enforcement cannot do it alone,” Gray said.

Sheriff Williams wants the community to see the human, not the inmate.

“We have to hold on to the human element so we can just look at people not as the sum of what they’ve done but also what people can do and what people can be,” Williams said. “We have to get back to just seeing people as human beings before we see any of these other things.”

As inmates get released, Athens-Clarke County programs can only carry them so far. It’ll take the village to carry them further.

Izzy Bisges is an undergraduate senior majoring in journalism at the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Fajorah Poteau is a senior majoring in political science and journalism at the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Morgan Phillips is a senior majoring in anthropology and journalism at the College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)