Growing up, I never really liked my last name. I’m ashamed to admit it now, but back then, the feeling was true. No one ever seemed to be able to spell it right or pronounce it correctly.

I began to appreciate my distinctive name once I got to high school. Teachers now stared at the attendance sheet with fascination, wondering which of their new students had the “awesome” and “cool” last name.

I began to feel proud of who I was. My name was original and probably had many stories behind it—I was determined to find more, but I never quite knew where to start. I’m not alone.

Why It’s Newsworthy: More than 3 million people subscribe to family genealogy websites to find out who they are and where they come from. With the help of a dedicated genealogist, a few family tree websites and my grandparents’ stories, I came to Germany to try and find new members of my family, the ones who didn’t emigrate to America nearly 100 years ago. Through my journey, I learned that it’s possible to overcome a language barrier and time constraints to find bits and pieces of information that can lead you to family.

Meeting the Relatives

Found them. And they sounded just as eager to meet me, their American cousin, as I was to meet them. The apartment of my third cousin, Clementine Kröninger, was just a short walk from my hotel. As I made my way to her place along the cobblestone sidewalks and through a large park with tall trees, I was excited and nervous.

Meaning Behind Name

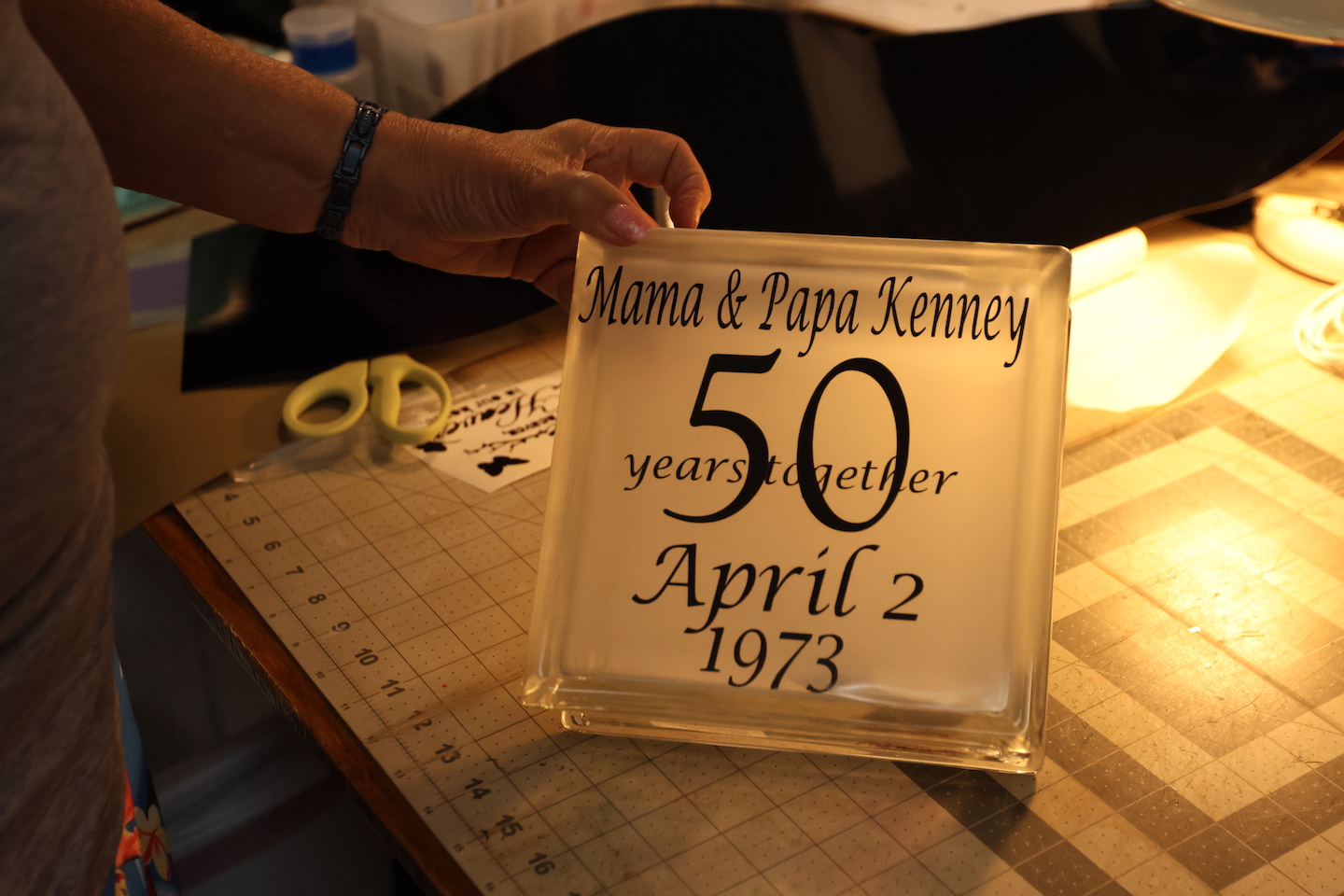

According to my grandparents, there were once three brothers who were hardworking blacksmiths in Germany. The middle brother was given the last name Mittelhammer because ‘mittel’ means middle in German, and blacksmiths use the ‘hammer’ or mallet to craft and shape their work.

The name stuck and was passed down through the generations.

I knew I wanted to follow my paternal grandfather’s line, but I only had a few names from that side of the family: My grandfather, Maximilian Mittelhammer Jr., and his father Maximilian Mittelhammer Sr.

First Steps

When I came to Munich for my three-week study abroad program, I already had a list of the names and addresses of four women related to the Mittelhammer family. I didn’t realize it until I started digging, but Clementine’s name was on that list.

After calling my grandparents and second cousin, I learned Max Sr. had two brothers named Karl and Josef. Karl moved to New Jersey along with Max in the 1920s. Josef fought for the German Army in World War II. His three daughters— Matil, Hilda and Theresa, came to the U.S. in the 1950s during the rebuilding of Munich. Theresa and my grandfather, Max Jr., are cousins.

My first task was to organize all of the information I had about my family. I had an old scrapbook from a school project filled with stories and pictures from my grandparents that provided some basic information and helped fill in some gaps.

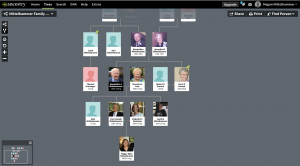

I made an Ancestry.com account, so I could add names, birthdays, places of birth and death dates for relatives as far back as my paternal great-grandfather. Then, Ancestry compiled the information and provided hints that indicated a census, travel log, Social Security application or photo of someone who could be my relative.

Getting Down to Business

After working on my own for as long as I could, I consulted a German genealogist and historian, Harald Nottmeyer, to help me locate information about my relatives who lived in Munich before coming to the U.S.

Nottmeyer, who is also the director of a local history museum in Munich, explained that finding legitimate sources of information about my ancestors would take time—much longer than the three weeks I had in Germany—and would involve a variety of sources.

“I work with certificates from the registration office and church,” Nottmeyer said. “Every person I find has to be proved by certificates of birth, marriage or death.”

Nottmeyer’s work deals strictly with locating public records. He explained that it’s helpful to go into the process of creating a family tree with a certain strategy in mind.

What do the documents tell us?” Nottmeyer questioned. “That’s the most important thing. And how will you create your line?”

Germans emigrated to the U.S. in the largest waves during the nineteenth century, Nottmeyer said. He explained that overcrowding in cities like Munich, lack of available farm space and economic hardships were some of the most common reasons for leaving the country.

My great-grandparents arrived in the U.S. just before the start of World War II. According to a report by professor Dieter Cunz, Germans had the second-largest foreign born population living in the U.S. in 1930 at 1.6 million residents.

Nottmeyer instructed me to find Maximillian Sr.’s birth certificate. From what I was told by relatives back home, he was born in the town of Zorneding, just a 30-minute train ride outside of Munich.

Lost in Translation

I arrived in Zorneding on a wet, stormy day and walked through puddles and quiet streets to the steps of the small town hall. This was the place where Nottmeyer said I could access a copy of my great-grandfather’s birth certificate.

After struggling through introductions and explanations in English and broken German, I made it into the town hall office only to find that there was no record of Max Mittelhammer from 1900 through 1914.

Frustrated and confused, I was starting to wonder if I was in the right place. I remembered that my relatives said there was a family cemetery in Zorneding, so I made my way there. After walking through rows of headstones, there was no sign of the Mittelhammer last name.

I decided to call my grandparents to see if they knew the answer. They explained that it was my great-grandmother Vera, not Max Sr., who was born in Zorneding.

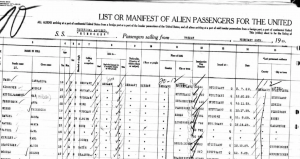

With Nottmeyer’s help, I found the passenger list from the ship my great-grandfather took from Germany to New York. He landed in America in 1929 after leaving Bremen, Germany on the S.S. München and settled in New Jersey. The manifest listed Osterhofen as his place of birth.

Unfortunately, Osterhofen is too far away from where I stayed in Munich to be able to visit. While I didn’t find the information needed on the paternal side to continue expanding my tree with Nottmeyer, I knew that I had at least walked through the same streets as my great-grandmother in Zorneding and visited a place where she spent a portion of her life.

I used the information from my list of relatives to track down Clementine. It took some broken German phrases and lots of explaining to convince her that we were related. Once we texted back and forth and put the pieces together, she was willing to meet me.

Moment of Truth

Clementine and her mother, Theresa, opened the door to their apartment with welcoming arms. They repeated how eager they were to meet a relative from the U.S. whom they really didn’t know existed.

Surprisingly, they found my first name more interesting than my last. Theresa kept saying it reminded her of “the princess,” Dutchess of Sussex Meghan Markle.

As we talked and shared stories around Theresa’s kitchen table—decorated with her finest china and topped with the cakes she spent all day baking for my arrival—I couldn’t help but sit there in awe. I had found flesh and blood relatives who most of my family didn’t know existed.

Finding Refuge

Soon after we sat down, Theresa hurried over to a small chest of drawers and pulled out hand-stitched patches with American logos and designs, including one with the presidential seal. Her voice was soft as she fondly recounted her time in the U.S. after World War II.

“I worked in America,” Theresa said. “Eisenhower was the president when I was there.”

“They made them in the factory she worked,” Clementine added. “Germany was nothing, so it was a chance to work and to earn some money because here it was not so easy to make some money.”

According to an online publication from the Library of Congress, 580,000 Germans immigrated to the U.S. from 1951 and 1960. Theresa was one of many who had the opportunity to leave an economically-unstable Germany and create a better life for herself.

While Theresa’s mother stayed in Germany, she and her two younger sisters travelled to the U.S. Her father fought for Germany in Russia during World War II.

“He never came home,” Theresa said sadly. “My mother, she grow [sic] us up.”

Theresa stayed in the U.S. for eight years with my great-grandfather Max Sr. and his brother, Karl.

“I had a good time in America,” Theresa said. “I’m very thankful still today that I could go there.”

Who Cares?

Today, more and more people are curious about the world around them. Many are especially interested in how far they can travel back in time to understand their family’s history.

According to Ancestry.com, more than 15 million individuals are registered in its DNA network. The company also has more than 3 million paying online subscribers.

Even Nottmeyer said he enjoyed the process because he is curious about his own family.

“The older I get I want to do some family research because I find it interesting how people here from Germany emigrated to some part in the world,” Nottmeyer said.

Today, immigrants travel across the world and leave old their lives behind for some of the same reasons from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Since 1850, 44.5 million immigrants came to the U.S. due to conflict, persecution, poverty and inequality, according to an article from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Only The Beginning

At the end of our time together, Clementine told me about more Mittelhammer relatives who still live in New Jersey. After getting to know these relatives I didn’t know existed, I’m hopeful to find even more family members once I return to the U.S.

As an only child, I’m the last generation of this particular line of Mittelhammers. With the help of family genealogy websites and DNA tests, it’s now easier than ever to learn as much as I can about my family.

The next time you find yourself traveling close to where you have family roots, do a little research before you leave. That research could make your vacation more than just good food, amazing views and cute selfies. You’ll be embarking on a whirlwind journey to find out who you really are.

Megan Mittelhammer is a sophomore majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.