With the Nov. 3 Election Day on the horizon, there’s still a wave of uncertainty around everything from methods of voting to what elected officials will be taking over in the aftermath. People with disabilities in Georgia and around the country are also dealing with that uncertainty ahead of the election.

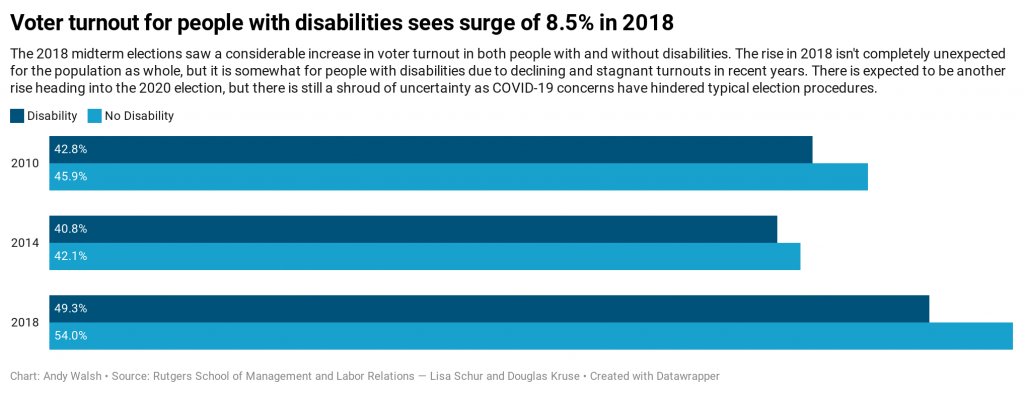

Why It’s Newsworthy: According to a study by Rutgers University which analyzed the federal government’s Current Population Survey Voting Supplement, 14.3 million citizens with disabilities reported voting in the November 2018 election. An 8.5% increase in voter turnout for people with disabilities between the 2014 and 2018 midterm elections showed progress after years of stagnant or declining numbers. Although there was a surge, those 14.3 million voters are only 49.3% of the potential voting population for people with disabilities in America.With those numbers in mind, another rise isn’t out of the question. For nonprofits like the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities, finding out ways to continually aid and educate the community is key in helping those statistics rise in the upcoming election.

Eric Jacobson, executive director of GCDD, is remaining optimistic despite some of the worrying developments this year.

“We believe that the disability vote has been always undercounted and that what we’re able to do — if we get people to vote — is we’ll create a stronger block,” Jacobson said. “We would hope that this election would build off the last elections so that we have even greater numbers.”

The Obstacles

Roger Keeney, a 73-year-old Athens resident who is blind, cannot cast his ballot without a talking voting machine or the help of someone else. But he wasn’t worried about the complications he deals with at the polls; he was more focused on physical barriers for people with disabilities like inaccessible buildings and rooms.

“Unfortunately, folks that don’t have to rely on things like wheelchairs, etc., they don’t notice how inaccessible some places can be, and particularly [in] inside situations,” Keeney said.

Keeney is also worried about potentially being exposed to COVID-19, saying that he will vote via mail this election season strictly because he is a “prime target” to contract the virus due to his age — similar to many people across the state and country.

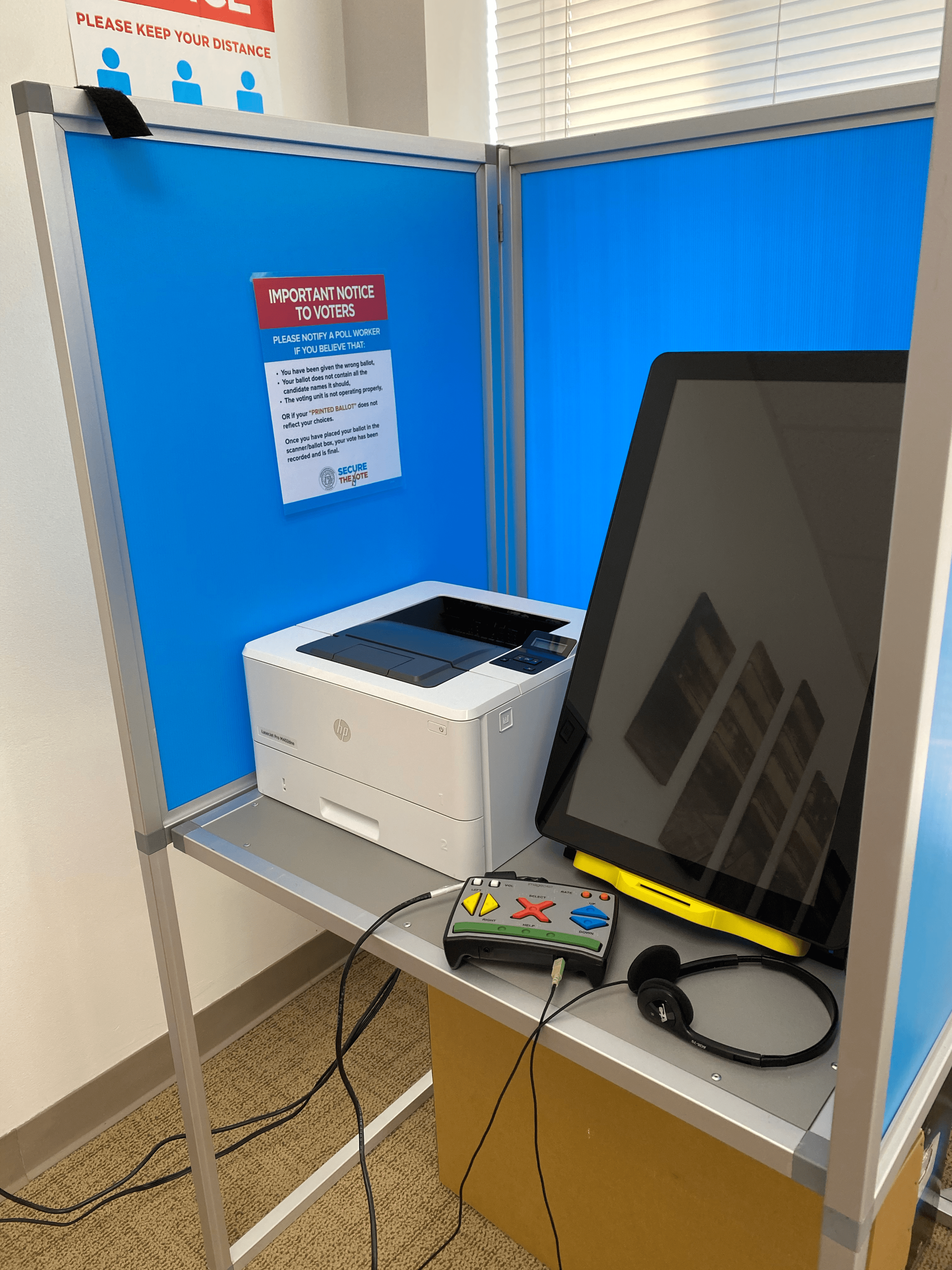

For those in Georgia who still plan on going to the polls on Nov. 3, many will use the new voting machines that were first introduced during the presidential primaries earlier this year.

The voting machines were brought in to ease any concerns about malfunctioning voting equipment ahead of the 2020 elections. Those concerns have been a hot topic since the 2018 gubernatorial election, in which Gov. Brian Kemp defeated Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams with 50.2% of the vote.

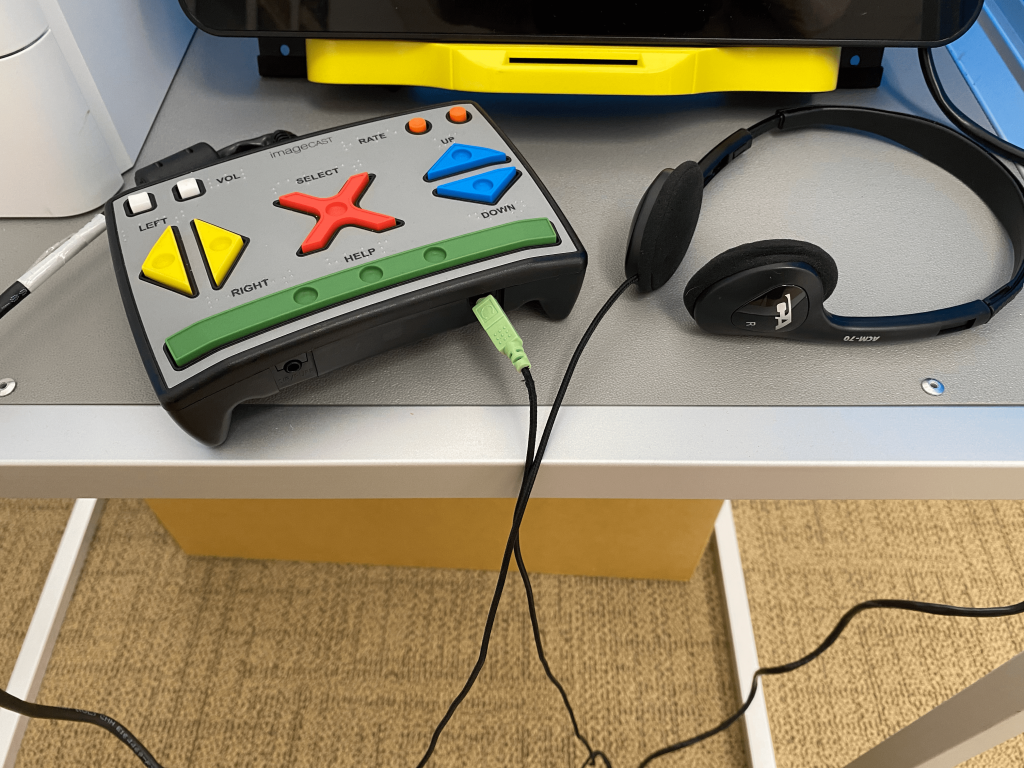

However, the new voting machines have managed to create some unforeseen questions for people with disabilities, especially those with a visual impairment. The machines feature an electronic touchscreen as the first part of the voting process. There is a controller and headset for people who are blind or visually-impaired.

For Danny Housley, who is blind, that controller wasn’t at his polling location during the rescheduled June primaries. Housley, who works as the assistive technology acquisition manager at Georgia Tech’s Assistive Technology Act Program Tools for Life, waited for four hours before the proper device was available so he could cast his vote.

Three poll workers offered to read out the ballot and help Housley make his selections. He turned them down because of privacy and verification issues, but also because he’d prefer to cast his ballot independently.

“They wanted to make sure that I got out in a reasonable time and that I was able to cast my ballot,” Housley said. “They cared about being able to cast the ballot; it was just kind of a wrongheaded way to approach that, but again, the intentions were good.”

The verification of the votes is difficult for people with visual impairments. After utilizing the electronic touchscreen, the machine prints out a ballot to be verified. People with visual impairments are unable to confirm their ballot without the help of a guardian or family member, a smartphone or digital magnifier.

Normally, voters aren’t allowed to bring phones or other electronic devices into the voting booth. However, a rule change made back in June allows people with disabilities to bring their assistive technologies into the booth. Come Nov. 3, the onus is on the poll workers to properly recognize those situations and allow the device to be used.

The Solutions

Poll workers for the Athens-Clarke County Board of Elections have spent the months leading up to the election hiring and training poll workers and testing the equipment. Lisa McGlaun, an elections assistant at the county’s board of elections, helps train poll workers and recognizes the different problems posed by the new voting machines.

“We do pretty extensive training on how to help the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] voters because the machines have to be programmed or the ballot has to be activated a certain way in order for the person who’s visually impaired to be able to hear the ballot,” McGlaun said. “So they do get a lot of training on that.”

Next, all polling locations must be approved to make sure they are accessible to people with different disabilities. There’s a checklist of things that must be checked before approval.

“Even if there’s only one person with a disability that comes, we have to prepare the same way,” McGlaun said.

McGlaun added that voters may test a machine at the downtown board of elections office and encouraged people to come and experiment with them before early voting starts.

Besides following state- and locally-mandated rules on elections, McGlaun said there’s a certain level of outreach with the community as well. This includes hopping on Zoom calls with different individuals and organizations to help educate them on how things might be changing ahead of the election.

It’s a situation that requires constant cooperation from Athens-based organizations, Georgia nonprofits like the GCDD and citizens like Keeney. For him, it’s crucial to maintain contact with relevant people or organizations that work in the community.

“Working from the bottom up and working with the folks like Lisa [McGlaun] is extremely important,” Keeney said. “We can, we have to speak up and work with the people that are local in our own community to begin the process of working through and making things better for ourselves and other folks with disabilities. If we don’t, we only have ourselves to blame.”

For people like Jacobson and the staff at GCDD, finding ways to work with state and local government to make voting easier than it has been in the past is always the goal.

Jacobson said Medicaid and other crucial services could be taken away if people with disabilities aren’t fairly represented at the polls. He is constantly reminded of that mission by a quote from Justin Dart Jr., an advocate for people with disabilities who helped pass the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

“Vote like your life depends on it, because it does,” Jacobson said.

Andy Walsh is a fourth-year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (1)