Tiny hands shot in the air when Nicole McGiboney asks a simple question.

“Who here has a garden at home?” she asks, expectantly.

An overwhelming majority of first-graders at West Jackson Elementary School are excitedly explaining what they grow in their gardens at home. One student has two rose bushes and a money tree while another grows carrots.

McGiboney works with Kathy Venable, a STEAM teacher at West Jackson Elementary. The elementary school is one of 10 STEAM-certified elementary schools in the state. The pair have worked together for the past couple of years to bring sustainability and agriculture to the classroom.

The pair first met after McGiboney introduced her to a grant opportunity that would give Venable a tower garden that sits in her classroom. It was not long before they realized their shared love of sustainability and passion for teaching it to the next generation of students.

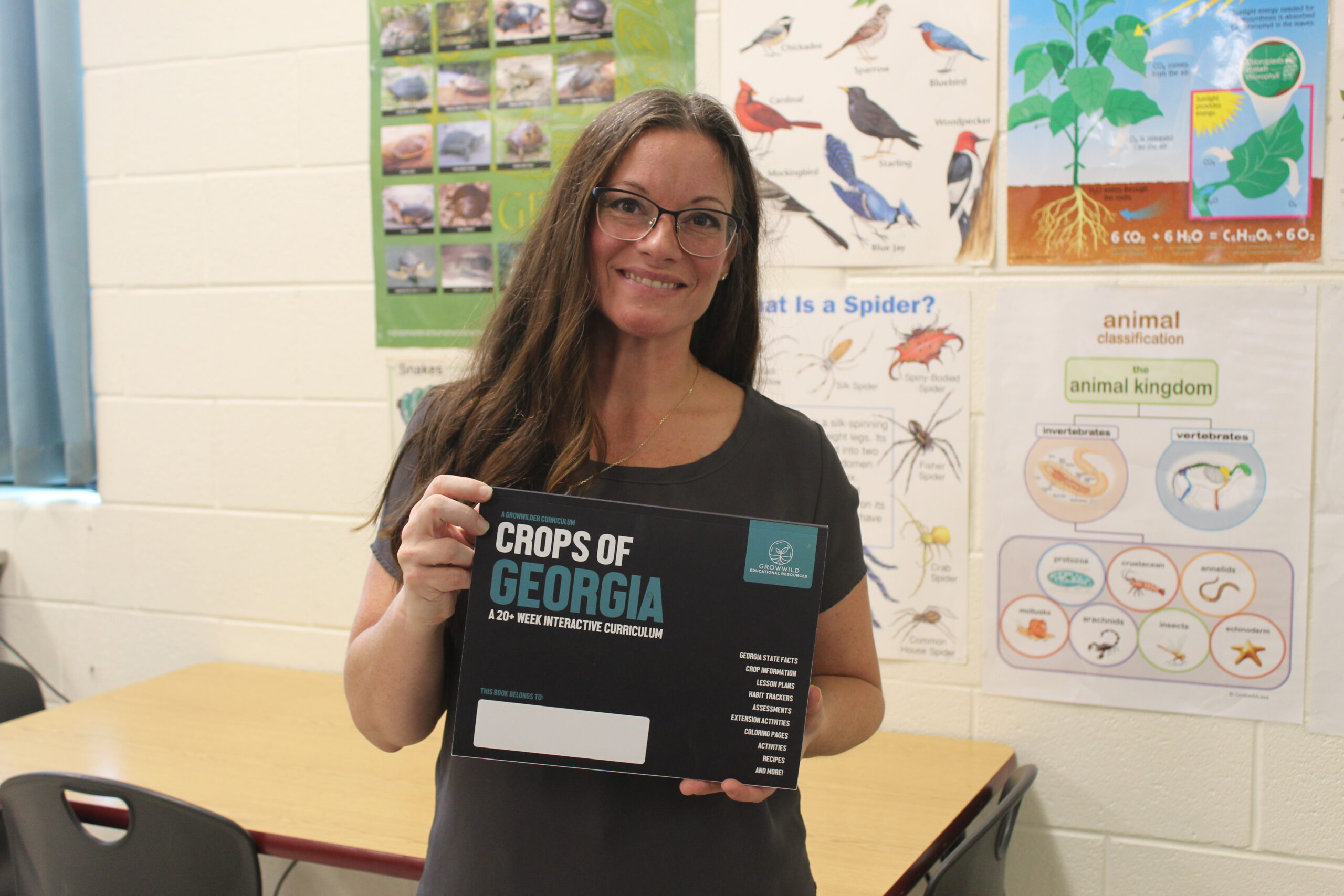

McGiboney is the owner and lead consultant of Grow Wild Educational Resources. She helps teachers and businesses become more sustainable by providing access to resources they might not have known about.

West Jackson Elementary was the first school she ever worked with. When McGiboney visits classrooms around Northeast Georgia, she brings presentations to show students how easy it is to grow their food and positively contribute to their environment. According to the National Institute of Health, home gardens help reduce carbon dioxide, which helps reduce the amount of global warming pollutants in the air.

McGiboney was inspired to share her ideas after making a change in her own life.

“Years ago, I was super unhealthy. I saw the trends in the nation and the way things were going. And I said, ‘you know, I need to do something.’ So I started with my own family” she said. “Myself and my children, we started growing our own food, and then I realized I should be doing this and helping other people.”

The services McGiboney provides extend outside the classroom. She’s worked with local businesses in Northeast Georgia to help make them more sustainable. In turn, she helps cut down production costs and eliminate waste. She introduces businesses to sustainable practices that she also uses.

“I try to be paperless. I have my paper in to write with or post like little note cards, and then I compost them and put them in my garden. So I just try to be as sustainable as possible. And I brought that to the community,” she said.

But where McGiboney thrives is in schools with teachers and students, so much so, that she calls herself “a teacher’s best friend.”

She takes her ideas to schools to teach students about local agriculture alongside their teachers. She has an entire tool kit of resources and crafts that she uses to get students excited about gardening, but this does not come without a cost.

The largest barrier stopping most teachers from enhancing the classroom experience for their students is the cost. According to the National Education Association, educators spend $500 to $750 of their own money every year to get additional resources for their classrooms.

However, McGiboney is helping lessen that burden by connecting teachers with resources and people in the community to bring innovative educational experiences for students. She found out that she has a knack for writing; through that, she has been able to help teachers apply for grants and create fundraising opportunities for schools.

Andrea Rowe, a STEAM teacher at Austin Road Elementary School, wanted to incorporate more gardening and agriculture in her lessons while she was a teacher at West Jackson. While working with McGiboney, Rowe applied for and became a fellow of the Food Education Fellowship. The fellowship gave her a set of food education lessons that exposed West Jackson first-graders at the time to more than the standard curriculum, a stipend and money for classroom materials.

“I just realized that I could teach kids where their food comes from and how important it is to take care of the Earth and the value in eating nutritiously, the value in respecting the land and what was there before us and what comes after us,” said Rowe.

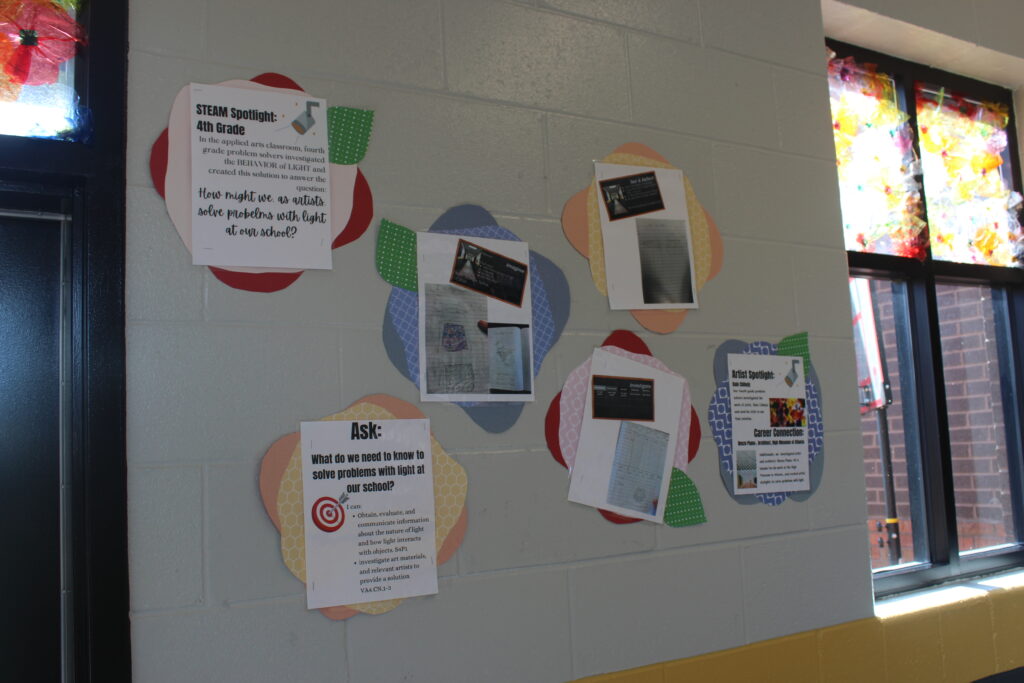

West Jackson Elementary shows how far grants and fundraisers can go. Students at West Jackson get opportunities to have hands-on experiences growing food inside and outside the classroom.

All around the school’s campus, there are different ways for students to see how they interact and affect their environment. There are composting bins where students can put their food scraps from lunch. There is a bee hotel, bat box and specific plants to attract local pollinators.

Many of the resources that help the 1,200 students at West Jackson Elementary understand how they interact and affect their environment were funded by grants and fundraisers. These experiences excite the students. Both McGiboney and Venable agree that students are more willing to eat and drink foods they would not because they took part in growing them.

“They can’t wait to drink a kale smoothie because they’ve had a hand in growing it,” said Venable.

What McGiboney provides to teachers and parents is changing the way students interact with things they used to avoid.

“But knowing that I can inspire those kids to eat [what] they’re not wanting to try at home,” said McGiboney. “That impact makes it totally worth it.”

Grace Saidi is a student majoring in journalism at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)