Sarah Thurman is proud of the growth that the Athens Farmers Market has experienced since she took over as market manager three years ago. In that time, she says that she has seen the number of visitors who stop by the market almost every Saturday morning from March through December nearly triple.

From rural counties like Hart or Habersham, to larger towns like Athens and Gainesville, Northeast Georgia is just one of many areas where farmer’s markets have begun to crop up in high numbers in recent years. Data from the United States Department of Agriculture shows that from 2008 through 2014, there was a 76 percent increase in registered farmers markets nationwide.

Why It’s Newsworthy: There is substantial academic debate about whether organic farms have better environmental practices than traditional farms, and whether the consumption of organic food is better for the environment than the consumption of traditionally grown food. As organic eating and farmers markets become more prevalent in Northeast Georgia, should environmental concerns present a legitimate reason to switch over from traditional sourcing? How much organic food is wasted in Athens compared to traditionally-sourced food?

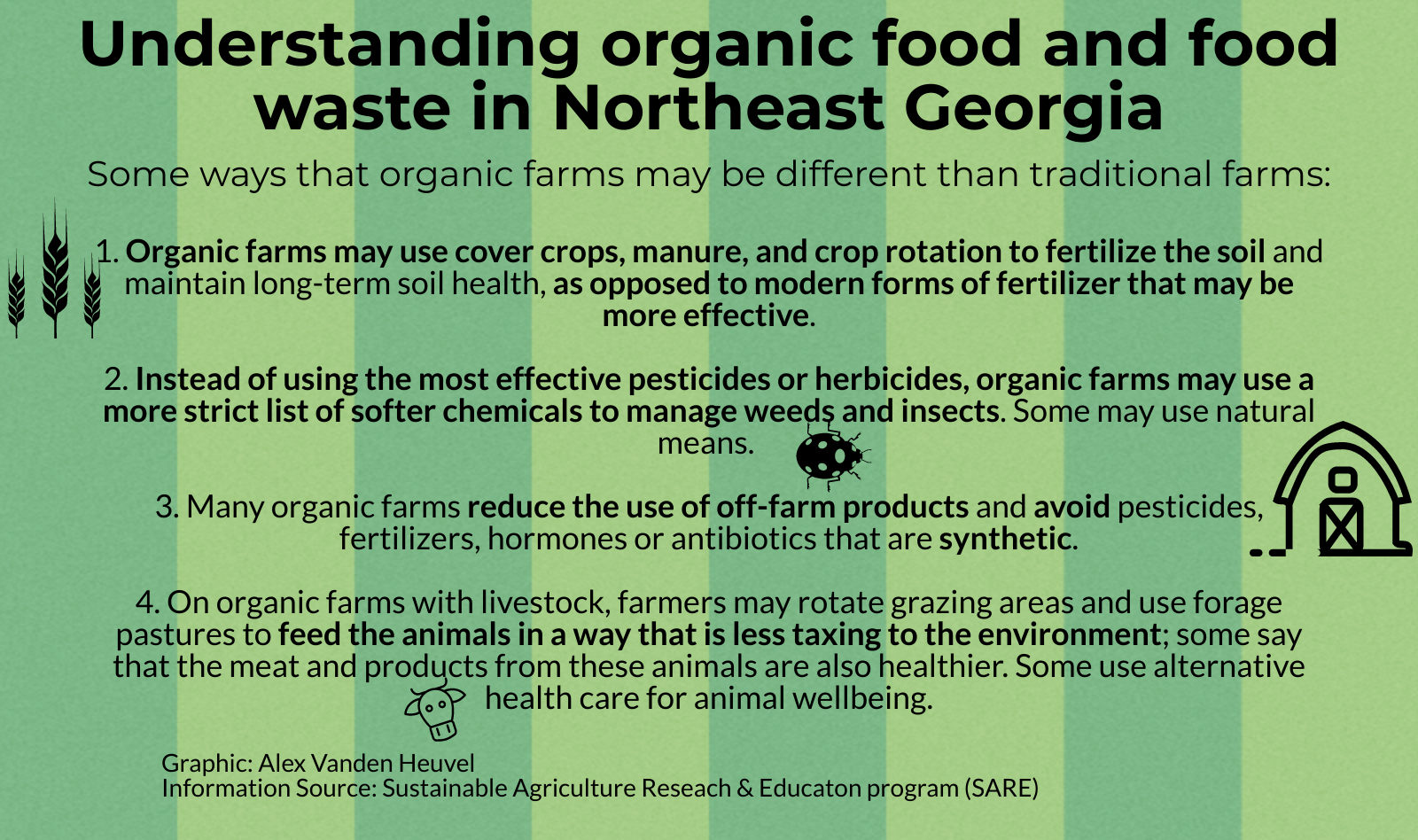

The markets increase the proportion of money going into a small farmer’s pocket for the sale of crops, increase accessibility of fresh food to low-income families who can potentially receive double SNAP benefits for food purchased at markets, and provide an opportunity for shoppers to buy food and agricultural products that are in many cases organically grown. The USDA says that “organic producers rely on natural substances and physical, mechanical, or biologically based farming methods to the fullest extent possible.” This means that many pesticides, most additives, and genetically engineered crops are prohibited from being used on organic farms.

In a time where more people are more aware of where their food comes from, there are many reasons that people buy organic food. Those reasons include a desire to support local business, a perceived need for food that is better quality or healthier, concerns over agribusiness farming practices or a desire to live a more eco-friendly lifestyle.

Thurman says that organic food, such as the produce that is offered at the Athens Farmers Market, is better for the environment than traditionally-grown food not only because the organic farming process is more eco-friendly, but also because she believes that organic food is wasted less.

“When you’re buying organic produce and it’s fresh, it generally lasts longer,” Thurman said, “You have a longer amount of time to decide to cook it and that creates less waste.”

Waste Not, Want Not

Thurman said that organic food is generally sold only a day or two after it has been picked. Most food sold at supermarkets has been transported for multiple days over longer distances to reach their destination. She said that some of the methods that agribusiness operations use to insure crops grow more uniformly in visually desirable ways tend to reduce the shelf life of the crops.

Thurman also said that when produce is organic, it tastes better, and is therefore wasted less because people are more willing to eat it. Buyers are also able to buy more precise amounts of produce and are not forced to buy produce that is prepackaged in larger amounts than they would otherwise need.

“Nothing is more depressing than buying something that looks pretty at the grocery store and coming home to realize that it tastes terrible,” she said, “Organic farmers are often selecting more for flavor than for appearance.”

Craig Landry is a professor at the University of Georgia in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics. He said one important factor that affects the level of food waste in a household is planning. Landry said often, an individual circumstance like the travel distance to a grocery store can either lead to more or less food waste depending on the planning skills of the subject.

“You shop, you kind of think about what you’re going to make, but you can’t predict exactly what you’re going to want,” Landry said, “And then sometimes you get a phone call, and hey, we’re going out to dinner. You were going to make something but then you don’t. So it’s kind of like the disconnect between the planning horizon and the consumption horizon.”

Things that make planning easier, such as longer shelf lives, more personalized buying quantities, and the perceived desirability that Thurman described could lead to relatively less food waste among organic food.

But Landry and his research co-author Travis Smith, a UGA professor specializing in the economics of food demand, both say that it is not that cut-and-dry. First of all, there is very little research about organic food waste specifically because a significant amount of the data used for dietary research is from previous decades before organic food caught on as a distinct concept.

One thing that is apparent from the research is that there is no one cause for food waste.

“It may be true that people who buy organic [produce] waste less food, but it also may be true that people who buy organic are different from people who don’t buy organic,” Landry said. “A lot of social science doesn’t try to tease out causality. For example, maybe organic food is wasted less not because it is better, but because the people who buy it are perhaps more environmentally-minded to begin with.”

Smith listed other factors determining waste, some of which could be linked to characteristics of the consumer, such as their culinary skill or income level. Other influences include produce cost, and expiration or sell-by labels, which Smith said are often misunderstood or poorly defined by the companies selling the produce. He said that the most common types of wasted food are produce and leftovers from restaurants; household meal producing efficiency has trended downwards since the 1970s.

Smith also said that due to the nature of research design a lot of food waste research is tainted by the Hawthorne effect, which is a psychological phenomenon in which research subjects alter their behavior due to the knowledge that they are being observed.

“Let’s say you want to know how much food people waste in Clarke County, so you randomly go to 100 houses and say, ‘Hey, instead of throwing your food in the trash, I want you to throw it in this bag right here,’” Smith said. “All of a sudden, people would be much more conscious about how much food they’re throwing away.”

A Problem of Scale

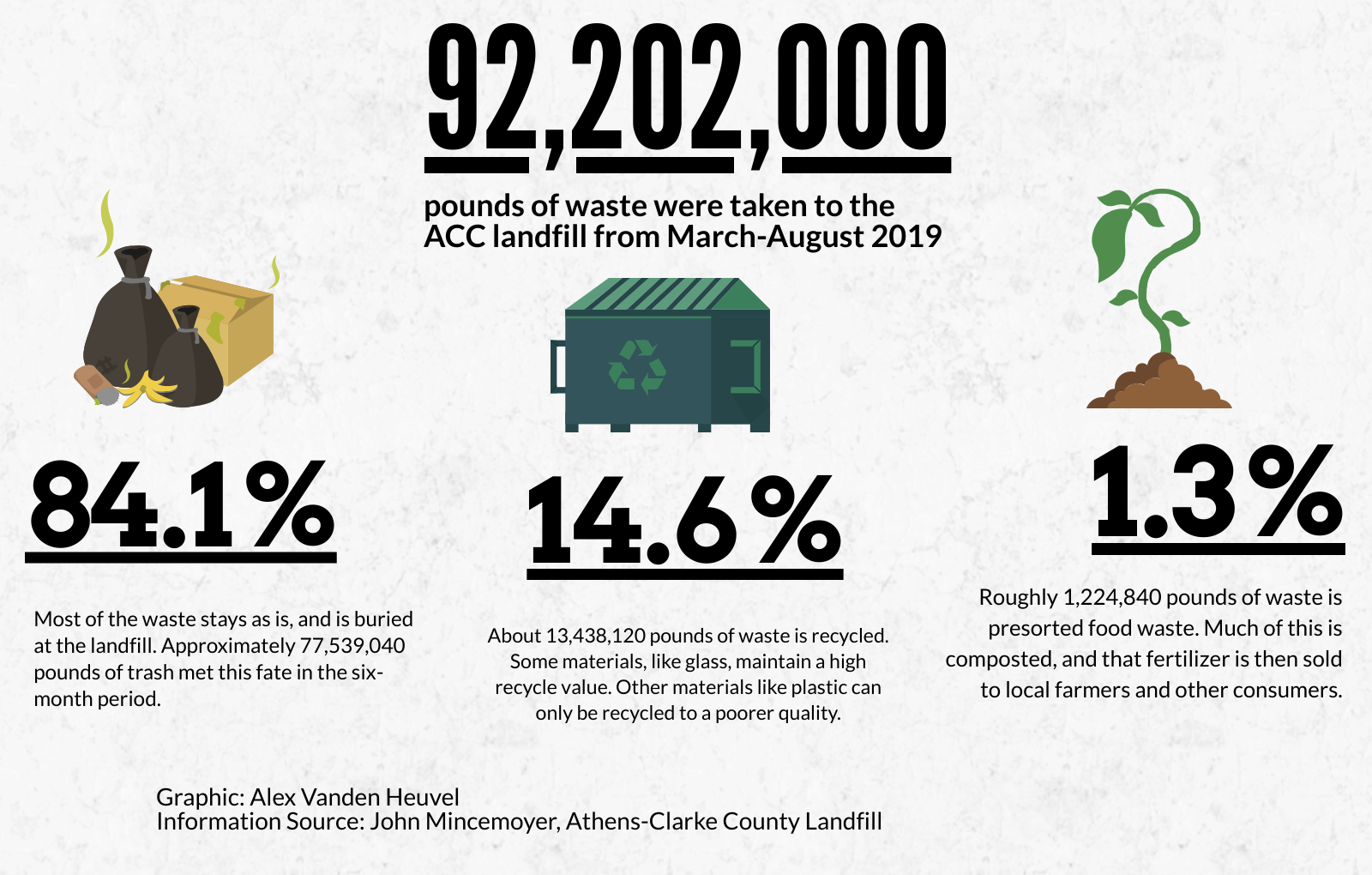

John Mincemoyer, the administrative secretary for the Athens-Clarke County Municipal Solid Waste Landfill, said the facility does not make a distinction between organically-grown food and traditionally-grown food, so there is no way to know what the breakdown is locally.

Between March 1, 2019 and Aug. 31, 2019, there was 612.42 tons of presorted food waste, some of which was used in the landfill’s composting system to create a compost mixture that is sold to consumers. It represents a tiny portion of the 46,101 tons of trash that was brought to the landfill during the same period. A lot of unsorted food waste ended up being lost in that larger share of trash. As for recycled goods, 6,719.06 tons of material accounts for the portion of the landfill’s intake during that six-month period.

Mincemoyer said a lot of that trash is derived from areas of town where the businesses almost certainly do not source organic, and he agrees there might be something to the idea that organic food is wasted less. But at the end of the day, the end destination is going to be the same.

“Athens is unique because of the university, and the influence of the student population. So we see spikes in trash. When the students move out we have a spike in May, and then we see a dip in tonnage when the students are gone in the summer, for the most part,” Mincemoyer said. “Then when late July, early August comes around we see that spike again, because of all the trash created from the move in. It’s like three, six, nine, and twelve on the clock.”

Back to the Start

On the production side, there is evidence to promote the idea that organic farming practices are better for the environment. Thurman, who spent several years working as an organic farmer before becoming the Market Manager for the Athens Farmers Market, said that a lot of it comes down to what organic farmers are choosing to use, or not use, during the growing process. The residual impact of many of the substances used manifests itself in ground water, soil composition and runoff.

“While [organic farms] do use pesticides, they tend to be of a softer variety that isn’t toxic to humans,” Thurman said, “a really popular one around here is actually a fungus that thrives within the body of the pest. When I was a farmer and I sprayed it to protect our greens, I wouldn’t have to wear a mask or gloves because it’s not dangerous.”

Mark Risse is the Director of UGA’s Marine Extension who also specializes in water resources and nonpoint source pollution management. He said that when managed properly, organic farms can be healthier for the environment than traditional farms because of the lowered runoff pollution.

Risse was reluctant to say in a sweeping generalization that organic farming is better for the environment than traditional farming because farming practices vary a lot. On organic farms, a lack of use in chemical fertilizers can lead to an overuse in manure, which puts an excess of a different substance in the soil to be carried away by groundwater or runoff. Risse mentioned that nitrogen is an example of something that can be carried away in runoff. Nitrogen tends to be overly depleted by traditional farming, whereas organic farming techniques tend to leave more nitrogen, which is usually better.

“It’s important to have nitrogen in the soil, because plants depend on being able to have it to grow. It’s like protein for us. If you don’t have sufficient levels of nitrogen, then you’re not going to get the plant growth and the yields that you need,” Risse said, “But having too much is a bad thing, because nitrogen is very mobile. And wherever water goes, the nitrogen goes as well. And it’s a plant nutrient that can impact our aquatic systems as well.”

Furthermore, Risse said in some cases organic farming techniques can be linked to more erosion due to tilling practices. Ultimately, he said that responsible decisions made by farmers affect the environmental impact of their farms more; on the margin, organic farms tend to be more eco-friendly than traditional ones, but only when managed properly.

Risse said that while the environmental benefits of organic farms are marginally noticeable across the entire industry, more significant benefits can be traced to organic farms that primarily focus on growing produce and not on raising animals. Many of the farms that sell produce at the Athens Farmers Market are primarily or exclusively dedicated to growing plants.

What Does It All Mean?

More so than any other factor, Risse listed reducing food waste as the best way to reduce humanity’s carbon footprint and fight back against climate change.

Smith said that at the end of the day, there needs to be a more cohesive conversation about what is defined as food waste. Different systems and metrics have differing definitions.

Is any food that does not reach a human stomach considered wasted? Should food that is composted count as waste? Should visually unappealing produce that is sold to second tier markets count as waste? These second tier markets include farms that use the produce as animal feed and the restaurant industry, since, for example, it does not matter if a tomato is ugly as long as it is diced in the kitchen. The second tier markets only pay a much reduced rate to the farmer. What about extra food planted or bought as an insurance policy against a bad harvest or an overcrowded party, but ultimately not used? People pay for insurance for years without reaping the benefits, yet few would argue that the payments made for insurance are wasted.

Thurman, Landry, Smith, Mincemoyer and Risse all agree on one thing—waste is driven the most by the decisions that people make every day, and those choices are what bear out more than the benefit yielded by any particular change in sourcing or diet.

“Think about it, we’re just one small landfill in one county in the state that has 159 counties, one state in a country of 50…” Mincemoyer said “When you see a trash truck driving through town, it might be filled to the gills with 13 to 15 tons of trash. That’s just one truck out of how many thousands running right now in the country; and that’s just one country in the entire earth. So it’s mind blowing to me the amount of waste that’s created.”

Alex Vanden Heuvel is a senior majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia. He is also majoring in political science and international affairs at the School of Public and International Affairs while working towards the Public Affairs Practitioner Certificate.

Show Comments (0)