Periods play a role in the lives of the majority of women who, in 2019, made up 44% of all NCAA athletes and 43% of all high school athletes, according to the NCAA and the National Federation of State High School Associations, respectively.

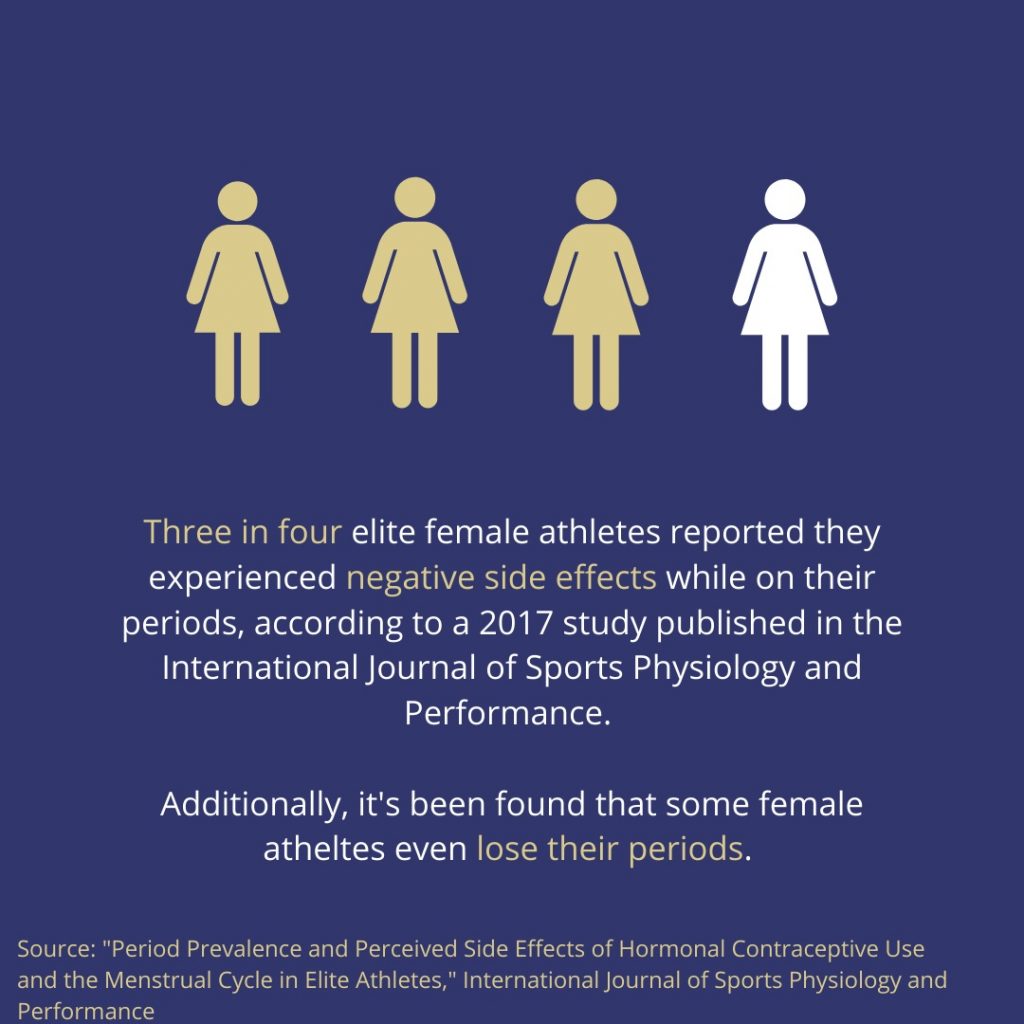

However, due to the taboos surrounding menstrual cycles, athletes may feel less comfortable bringing up any problems arising from their periods—or their lack of one altogether—which poses health risks.

Jessica Ma, a senior sociology and women’s studies major from Johns Creek, Georgia, and the UGA chapter president of national organization PERIOD, said the stigma surrounding periods stems from both generational and cultural norms concerning the menstrual cycle.

“There’s just a lot of negative connotations attached to the bleeding and the blood that makes it very shameful to talk about,” Ma said.

Misinformation concerning periods is another factor which lends to the taboo, Ma said, and is something PERIOD works to dispel.

Gender and Periods in Sports

Stigmas concerning periods carry into the sports realm as gendered notions impact how certain athletes are viewed.

Ilsa Ott, a junior cellular biology and anthropology major from Marietta, Georgia, ran cross country throughout middle school and then switched to competitive swimming while in high school. She now swims for UGA’s club team and talked about her experiences as an athlete.

I think that anything that makes you more female in sports is seen as a weakness,” Ott said. “It’s seen as like, ‘Oh, this part of my body or this part of my bodily functions somehow makes me weaker because it makes me more feminine.’”

Due to the nature of the sport, Ott said tampons were the only product she or her fellow teammates could use when they began their periods because menstrual cups weren’t as popular among her peers as they are now.

The taboo surrounding periods also made it difficult for Ott to openly discuss her period, or any complications arising from it, with her teammates or mostly male coaches.

Ott said there was an additional level of discomfort that stemmed from the tight-fitting swimsuits she wore, which put up an even greater communication barrier between herself and the coaches, especially concerning a topic she was already uncomfortable talking about.

Athletes Losing Their Periods

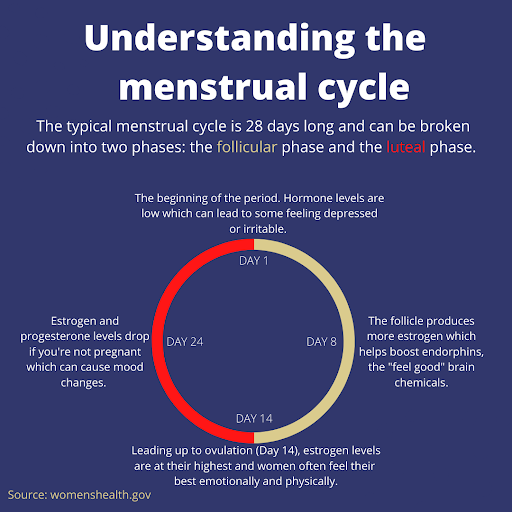

Amenorrhea, the medical term for the absence of menstruation, and hypothalamic amenorrhea, when the brain doesn’t send specific hormonal signals, is what happens when athletes lose their periods, said gynecologist Petra Casey in Women’s Wellness: Female athletes and their periods, an article on the Mayo Clinic website.

Casey described how losing one’s period over an extended amount of time can be damaging because one does not receive enough estrogen. Without the estrogen, bones tend to become thinner and there are increased chances of developing osteopenia or osteoporosis, which may or may not reverse itself.

Emily Doherty, a junior majoring in human development and family sciences from Athens, Georgia, is a distance runner for the UGA track and field team. She said she has seen the impact of losing one’s period through the experiences of some of her teammates.

Listen to Doherty’s story here.

Junior Rachel Doxey hasn’t had her natural period in two years due to hypothalamic amenorrhea. Doxey, a food science major from Evans, Georgia, works out 21 hours a week. She runs competitively, cycles for fun and instructs multiple cycling classes.

“At one point, I’d always joke. I’d be like, ‘It’s so cheap because I don’t have to buy tampons or like, it’s nice I don’t have to worry about wearing my pants,’” Doxey said. “But it’s been going on for so long that there’s definitely some frustration with it.”

Physicians have suggested she work out less to see if that would induce her period, but Doxey said this task is more difficult said than done.

“I have some sort of identity with my active lifestyle,” Doxey said. “It’s that same frustration I feel now. I’m like, ‘I know something’s up. I want to get my period back,’ but it’s me fighting against myself.”

Doxey expounded on the appeal of getting her period back.

“If the hormones are imbalanced in my body, does that mean my body’s imbalanced? What could I be capable of doing if I was in balance?” Doxey said. “It’s always that wonder of like, ‘if this was fixed, then my period should be fixed. Then I would know I was alright.”

Future of Periods and Athletes

Years of intense training and dedication brought Fu Yuanhui, a Chinese swimmer specializing in the backstroke, to the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. While she received a bronze medal for her 100m backstroke, she garnered even more media attention for opening up about her performance in the 4x100m medley relay and the fact that she was on her period.

Fu, doubled over in pain, told a reporter shortly after the race that, while it wasn’t an excuse, she had started her period the day before and was feeling weak and tired.

She became a national icon, and many rallied behind the young athlete in support. Ott said she remembered hearing about the interview and was sympathetic toward Fu as a swimmer who has also experienced pain while on her period.

However, Ott said she didn’t notice any changes surrounding the stigma of the subject following Fu’s statement and instead encountered conversation in which Fu’s mensuration was deemed a sign of weakness.

“It is very tricky to have conversations where you admittedly like say, ‘My period makes me not perform my best or feel at my best’ without someone twisting your words and using them against you.”

“[Such as], ‘you must be weaker because of that, or this aspect of how your body functions makes you less competent than somebody else,” Ott said.

Pushes for transparency are trending nationally across subjects and platforms and the health concerns of female athletes are not falling by the wayside.

In November 2019, Mary Cain, once considered the fastest female runner of her generation and a runner for Nike’s Oregon Project, shared how the intense exercise regimen and culture to stay skinny eventually broke down her body. The story and video interview were published by The New York Times and went viral, sparking conversation concerning image and health concerns for young, female athletes.

Cain and Fu’s stories are only the first steps in a long conversation. Ott said the cultural shift toward making conversations concerning periods easier begins with normalizing menstruation and its correlated side effects on a national scale.

“That’s not something that you can change overnight, unfortunately, as much as I wish I could push a button to make everyone comfortable talking about it,” Ott said.

Ending the stigma around menstruation is one of PERIOD’s top priorities. UGA’s PERIOD chapter president, Ma, said gaining visibility through social media and fundraising campaigns are some of the organization’s efforts to normalize conversation around this topic.

“The name of our organization is PERIOD, so you can’t really avoid it,” Ma said. “And the more that we insert those messages and conversations into everyday life, the more people will realize that it’s just a normal part of life.”

Hawa Camara is a senior majoring in journalism at Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication with a certificate in entrepreneurship from the Terry College of Business, both at the University of Georgia.

Erica Jackson is a fourth-year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication with a minor in Spanish in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Georgia.

Rachel Priest is a senior majoring in journalism and history in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, respectively, with a minor in French at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)