When University of Georgia senior Van H., who requested that his last name not be used to protect his privacy, decided to change his name, asking his friends and family to call him Van was the easy part—legally transitioning would prove to be more complicated.

Photo Identification Laws in Georgia, Other Strict States

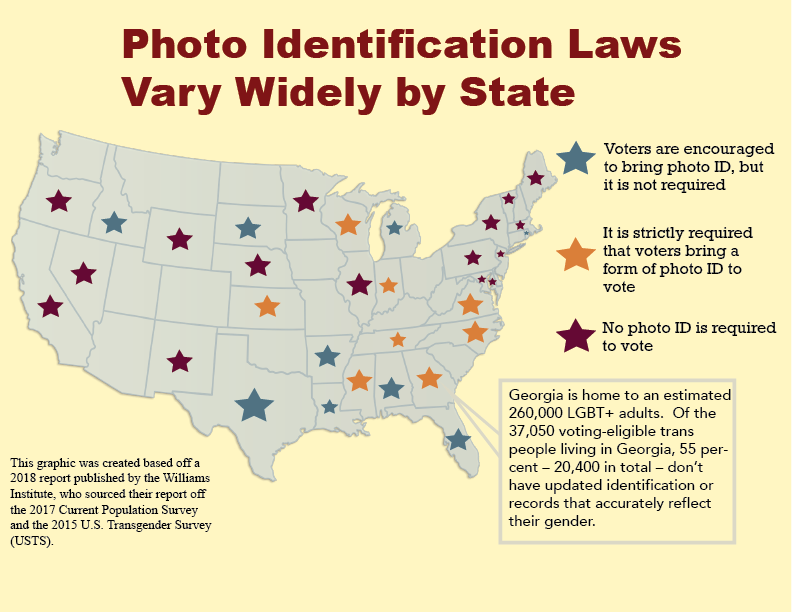

In Georgia, there are 37,050 voting-eligible transgender people, according to a 2018 report published by the Williams Institute, a think tank at University of California Los Angeles School of Law. Fifty-five percent of these individuals are legally known by their name given at birth, or what the trans community commonly refers to as your “dead name.” When driver’s licenses, passports and social security cards do not match a person’s gender identity or preferred name, complications can occur with legal processes such as voting.

Supporters of photo ID laws point to the alleged benefits to the state of requiring photo identification—including the deterrence of fraud and the greater belief in the integrity of elections. President Trump has expressed his approval of photo ID laws in the past and signed an executive order in 2017 to establish the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, a short-lived commission that was created to investigate vulnerabilities in voting systems.

Each state has jurisdiction over their own photo ID laws. For any given election, people living in certain states are not required to present photo ID when voting, while in other states, voters are strictly required to present photo ID. According to the Williams Institute, Georgia is one of eight states with laws that require voters to show photo identification at the polls. Of these eight states, Georgia has the highest number of trans voters who do not have updated government records.

Why It’s Newsworthy: In 2020, all 435 seats in the United States House of Representatives, 35 of the 100 seats in the United States Senate, and the office of president of the United States will be contested. Thirteen state and territorial governorships, as well as numerous other state and local elections, will also be contested. These elections will take place all across the country, and people should know their rights and requirements as voters.

(Infographic/Lilly McEachern)

(Infographic/Lilly McEachern)

How These Laws Affect Transgender Voters

When voters in these stricter states present their photo IDs at a polling place and their legal description does not match their physical appearance, they may be turned away and required to cast a provisional ballot. Provisional ballots are a placeholder for a final vote; the person must return with the missing information within three days of casting a vote.

“I do plan to vote. Everyone should vote!” Van H. said. “…I have never been fully stopped or restricted from voting. However, I get weird looks. Quite frankly, if I didn’t recognize the importance of voting, I might not just because I have to go and out myself as transgender to the poll volunteer just by handing them my license. It can be uncomfortable, but it doesn’t stop me. I hope the process can be reformed in some way for other members of the trans community…who may not be as willing to let a stranger out them.”

Another option is voting absentee, as mailing an absentee ballot does not require a photo ID. However, alternative methods of voting such as provisional and absentee ballots are at the center of an ongoing dispute about fair elections—668,000 voter registrations were canceled in Georgia in 2017 and multiple organizations have filed lawsuits claiming the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial election disenfranchised tens of thousands of voters, particularly voters of color, based on the state’s ‘exact match’ policy. Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger has denied the claims of voter suppression and requested that the judge dismiss the lawsuit filed by Fair Fight Action, an organization backed by Stacey Abrams, the Democratic candidate in the 2018 gubernatorial election who lost her bid to Gov. Brian Kemp.

(Infographic/Lilly McEachern)

Legally Changing Information Costly, Time Consuming

“No, I have yet to change my name,” Van H. said. “I am waiting until after I graduate just to make the process easier. The only time I face issues is when I am traveling out of the country. Any other time, people are mainly looking for age, so they don’t notice my name or gender. But when I’m entering another country, it can become problematic. I’ve never been fully stopped or not allowed to enter a country, but I’ve been given weird looks and asked to confirm the information, like address, on my passport.”

In Georgia, you are not allowed to change the gender marker on a license without a physician confirming you have had “sexual reassignment surgery,” a surgery only about a quarter of the trans population ever undergoes, according to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Overlapping federal laws allow citizens to change their gender marker on a U.S. passport without going through gender confirmation surgery.

(Infographic/Lilly McEachern)

Transgender and gender nonconforming people face unique obstacles when presenting government-issued documents. They run the risk of being outed, humiliated or even harassed. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 3 percent of respondents who were citizens and of voting age at the time of the 2014 midterm election were not registered to vote because they wanted to avoid anti-transgender harassment by election officials. Black respondents, who made up 7 percent, were also more likely to report that they did not register to vote in order to avoid harassment by election officials.

This election year, 78,000 voter-eligible trans people will be voting in states with strict photo ID laws. Organizations such as Georgia Equality and National Center for Transgender Equality educate and advocate for voters who are at risk of being turned away at the polls.

Lilly McEachern is a fourth-year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)