(Photo/Joshua Benefield with J.A.B Photography)

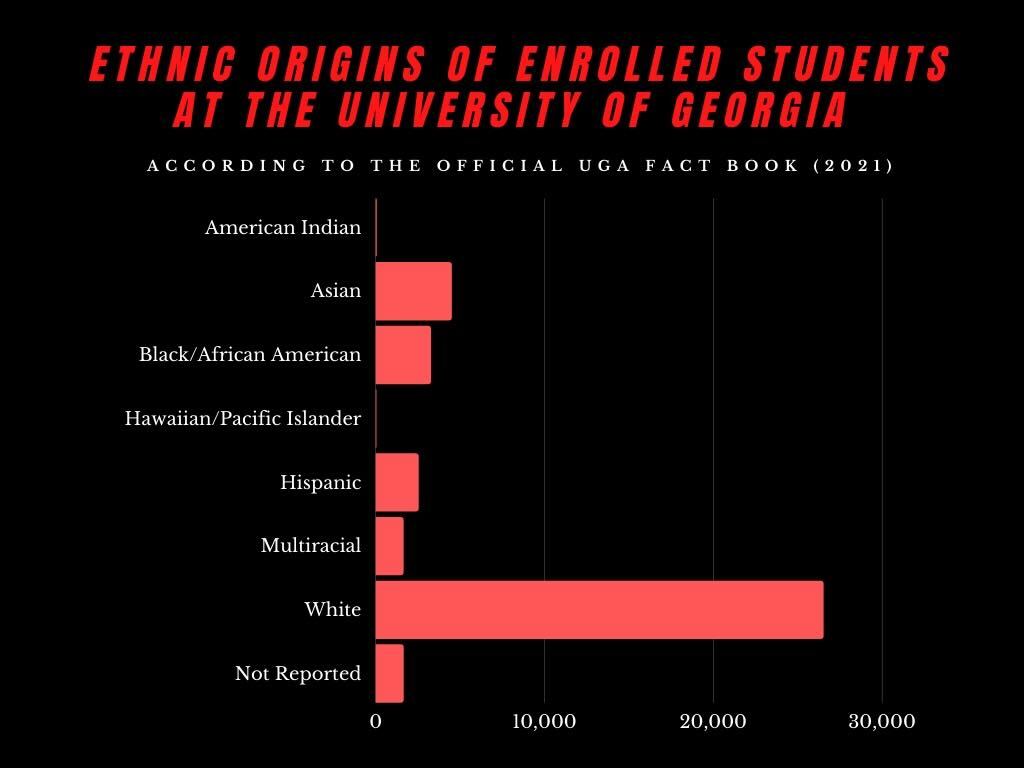

College dropouts have a grip on the U.S. economy, amounting to $6.2 billion in taxpayer money lost after students make the decision to call it quits.

A substantial 30.6% of those dropouts are Black students, according to the Education Data Initiative and the American Institute for Research. That’s nearly double the number of white dropouts. Furthermore, taxpayers will absorb $31 billion due to dropouts defaulting on student loans.

One factor that may contribute to this economic crisis is Black students leaving predominantly white institutions (PWI). The University of Georgia is working to turn those numbers around by creating more opportunities for Black students, and the students are coming together to craft their own experience.

Why It’s Newsworthy: In the United States, college dropouts generate billions in economic loss. Developing initiatives to foster a more inclusive campus can keep students in school and save people from paying for someone else’s decision to drop out.What Happened? A Look at the Historical Context

“From its very start, the school largely was about the perpetuation of inequality, disadvantage and privilege. And it’s rooted in the fact that African Americans were not allowed to attend UGA before 1961,” says Chana Kai Lee, associate professor of history at the University of Georgia.

Lee says from the establishment of the University of Georgia, UGA participated in slavery and the use of enslaved Black laborers. Enslaved people were involved in the building of the university before classes began in 1801 and worked there until the end of the Civil War.

Desegregation did not come to UGA until 1961 when Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter became the first Black students to be admitted into UGA.

It was not an easy process with multiple attempts by UGA to keep Holmes and Hunter from getting into the school. Ultimately, the university had to abide by a judge’s order and admit them both, ending 175 years of segregation at UGA.

“It was not a happy moment; it was a difficult moment. Eventually, of course, they were admitted and went on to graduate, but it was a time of struggle and strife for the university,” says Lee.

In response to integration, there was rioting. When Holmes and Hunter were admitted, they were met with crowds of people shouting racial slurs and chanting “two, four, six, eight. We don’t want to integrate.” And just a few days later, outside of Hunter’s dorm, a riot broke out with people throwing bricks, rocks and water bottles.

“UGA was forced to integrate. It was not something that people just decided out of the goodness of their hearts; it was something that they needed to do, that the time had come,” says Lee.

Although there was a grim response to integration at UGA, Lee says there were some important white faculty members who stepped forward and played a role in giving a voice to desegregation. For example, a math teacher asked his students to write about segregation and what it meant to them. And Horace Montgomery, a history professor, stood up and opposed UGA’s resistance to integration.

Charles S. Bullock, a political science professor who began teaching at UGA in 1968, says in the late 60s and early 70s, it was rare to see a Black student on campus.

Bullock even says it wasn’t until the late 1970s that he had a Black student in one of his classes, but that might’ve been because Black students were primarily majoring in other subjects.

“You could easily imagine that in the late 60s if you were a Black student, you certainly heard about the difficulties that Charlayne and Hamilton encountered, you might think, ‘Why do I want to subject myself to that?’” says Bullock.

Bullock says that 50 years ago there were some “pretty racist faculty members.” He mentions one specific example of a professor and if you were a Black or female student in their class it was known that you were not going to do well. Bullock would even encourage some students to not take that professor’s class if they mentioned taking it.

According to Bullock, aggressive recruitment of Black students and convincing them that UGA would be a place where they would be treated fairly possibly pushed Black enrollment. Bullock also suspects that the addition of the Hope Scholarship in 1993, giving students an opportunity to get a good education with little out-of-pocket expense, drove it as well.

Lee says college admissions are a competitive process when it comes to schools recruiting Black students, especially against historically Black colleges.

“I think it’s really hard to sell the place [UGA]. And it’s partly the history that students are still kind of wary of,” says Lee.

Who is Affected?

Take a look at a few UGA students who shared their PWI experience.

What’s Happening? What UGA Is Doing About It

While Lee explains the skepticism of some students, the general opinion on the reasoning behind choosing this institution has notably shifted.

Marques Dexter, assistant director of student affairs in the Office of Institutional Diversity at UGA, has firsthand experience regarding today’s recruitment and parental concerns.

“Parents and families are just really amazed at how much we are really providing key opportunities, resources and experiences for students to be successful,” says Dexter.

But just as important as the work Dexter and their colleagues are doing in the name of diversity and inclusion is what the students are doing for themselves. Dexter says that Black students are creating their own space.

“These individuals, our Black students, are very much so resilient in terms of how they are cultivating their experience and what they want here,” says Dexter.

Dexter explains that UGA’s Black students have much to show for the work they have done in making UGA theirs, too. Student-led organizations like Georgia Daze and the less formal community, BUGA (Black UGA), have resources in place to make the environment of a PWI more welcoming, such as weekend visits and tours around campus or Tate Time.

Morgan Finch, Georgia Daze president, is on the frontlines of this pursuit, saying she is passionate about developing valuable experiences for UGA’s Black students.

Georgia Daze is known for bringing interested Black students to UGA in an effort to show them around campus and talk with current students. While she wants to create an exciting and amicable atmosphere at UGA, Finch makes sure that incoming Black students know the truth.

“I make sure my ambassadors are authentic to these students. Tell the truth. We’re still Black students on a white campus and we still go through things, and their authenticity is appreciated,” says Finch.

This “truth,” however, is anything but an obstacle, says Finch, as Georgia Daze was founded on the experience of being part of the Black community at UGA.

“It’s great to be Black here at UGA; we’ve got a whole community,” says Finch.

And Lee adds to this, saying, “I’m struck by how much Black students feel isolated, or sort of off to themselves. Many of them are able to sort of create their own sense of community, but many of them when they first enter, they tell me how they feel kind of alone and isolated.”

Besides their main weekend visit event, Finch says that Georgia Daze puts on other events as well including Exposé, a student affair dance with a DJ, food, and Black vendors on campus. Additionally, the Office of Institutional Diversity organizes GAAME, a project of the University System of Georgia’s African-American Male Initiative (AAMI) focusing on the retention of Black males at UGA.

As the staff and students of UGA continue to forge more inclusive and united environments around campus, Dexter realizes this is all still a process that takes time.

“We have to continue connecting,” says Dexter. “The more we do that and be inclusive overall and model these practices, that will pay dividends and hopefully bring more students to our campus.”

Angel Sarpong, Erin Johnson, Jordan Stevenson, Mariah Rose, Reeves Jackson, and Jace Poole are a team of seniors majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (2)