Imagine it: You are sitting on your back deck watching your kids playing in the yard. Off in the distance you see a growing cloud of dust headed straight in your direction. You’ve seen this before. It’s the hogs, about 30 to 50 of them. You know you only have 3 to 5 minutes to get your kids inside to the safety of your home. You better act quick.

Pretty horrifying, right?

As one Arkansas man put it, this is indeed the case.

Legit question for rural Americans – How do I kill the 30-50 feral hogs that run into my yard within 3-5 mins while my small kids play?

— Willie McNabb 🐗 (@WillieMcNabb) August 4, 2019

The absurd image of violent, bloodthirsty pigs attacking small children at incredible speeds soon caught the attention of Twitter, and quickly responded with a flurry of memes.

https://twitter.com/jhermann/status/1158448132323192833?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1158448132323192833&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.vox.com%2Ffuture-perfect%2F2019%2F8%2F6%2F20756162%2F30-to-50-feral-hogs-meme-assault-weapons-guns-kids

What happened to the "Aporkalypse Now" novel?

— ribeyes4dinner 🌵🌊🌊🌊☮ (@ribeyes4dinner) August 8, 2019

https://twitter.com/alisarose_/status/1159237336577634304

for sale

30-50 feral hogs

never shot— rat liker (@rat_liker) August 5, 2019

At its core, we have to ask: how are rural Americans supposed to deal with the 30-50 feral hogs that run into their yard within 3-5 minutes while their kids play? Well for starters, it isn’t through Twitter. But it is a question worth posing.

Feral hogs pose a serious threat to the U.S. agricultural and livestock industries as well as native wildlife and the environment. The USDA estimates there are over 6 million feral hogs across 35 states, and their population is rapidly expanding. Estimates by the University of Mississippi report their range in at least 45 states, as far north as Michigan, North Dakota and Oregon.

And those hogs cause a lot of issues, costing the U.S. $1.5 billion each year in damages and control costs.

In Georgia, reported estimates are as high as $151 million in damages annually. This comes from a statewide survey by the University of Georgia, which estimates feral hogs cause $98.87 million in crop damages and $51.74 million in non-crop damages, things like fencing, roads and food plots, each year.

So they cause a lot of damage, but where do feral hogs come from, and how do we deal with them?

Why It’s Newsworthy: Across Georgia, the 10 million acres of farmland that bring in more than $3 billion in profit are threatened by a growing population of feral hogs estimated to be in all 159 counties.

How Did They Get Here?

Call them what you like, hogs, pigs, swine, boar, are all the same species: Sus scrofa. And they are not native to the Americas; they first arrived here with early explorers like Christopher Columbus in 1492 and Hernando de Soto in 1539, who first brought the hog to what is now the U.S.

Hogs made excellent livestock for explorers because they are highly adaptable and reproduce quickly, often producing two litters per year. They also are capable of fending for themselves which led to free-range management practices in the new world. Naturally, some of the hogs escaped and established the first feral hog population.

In the early 1900s, a new player was introduced: the Eurasian wild boar. This hog was first introduced in Hooper Bald, NC in 1912 for the purpose of sports hunting, but hunters soon spread them all across the southeast.

Today feral hogs are a combination of the cross-breeding between the two.

The Extent of the Damage

The threat feral hogs pose is multifaceted, ranging from crop and livestock damage to degradation to the environment and native species.

One of the most obvious forms of damage is to the farmers’ crops. Not only do the hogs eat them, they will also trample, root and wallow in the fields.

“It looks like a bomb went off in a corn field. All of the stalks are laying down, there’s pig scat everywhere, trample damage,” said Chris Boyce, a researcher at the University of Georgia who studied wild hog damage to corn and peanuts.

Boyce found that there was a critical period—when first planting their seeds—that farmers have to be weary of pigs.

“Pigs root down whole rows,” said Boyce. “They don’t even change rows sometimes, they’ll just pick one and move down it, digging up every single seed in the line that the farmers put in.”

But the damage doesn’t stop there. Feral hogs are susceptible to parasites and infections, which threatens domestic livestock primarily through the transmission of diseases. But hogs are ferocious eaters and opportunistic omnivores, and will readily consume livestock feed and even newborn sheep, goats and calves when given the chance.

In addition, hogs pose a serious threat to soil and water quality. Through rooting, wallowing and trampling, hogs compact the soil, which in turn disrupts water infiltration and nutrient cycling.

And, feral hogs are dirty. Remember that saying—pig sty? When hogs wade in streams, dirt and bacteria are flushed downstream, raising fecal concentrations beyond human health standards.

That damage is just in rural areas. Feral hogs are also known to make their way to suburban areas, destroying parks and golf courses and consuming lawns and gardens.

So What Can Be Done About Feral Hogs?

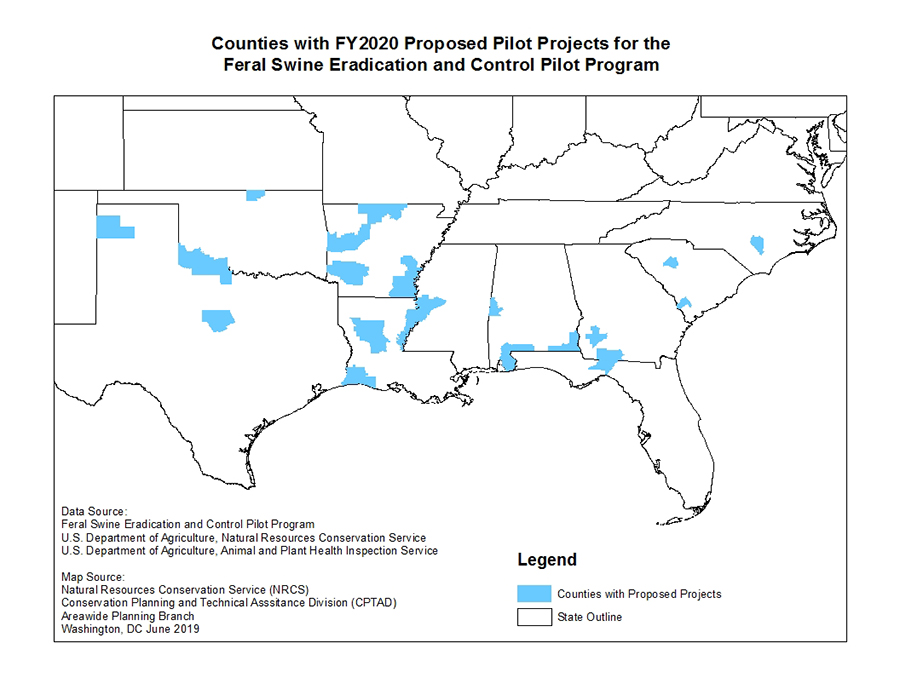

The 2018 Farm Bill established the “Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program” in response to their growing population. The program, set to begin later this year, provides $75 million in funding over the five-year life of the bill. Joint coordinated efforts by the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health and Inspection Service will work to remove hogs, restore land and provide needed assistance to farmers.

This bill is a step in that direction, yet its reach is limited. For the first round of funding, 20 pilot projects have been identified across 10 states, which is great, for those areas, including the two projects located in south Georgia.

Unfortunately for many areas across the country, including Northeast Georgia, this means no funding will be provided. For now, they have to continue to manage the hogs themselves.

According to Michael Mengak, a professor at the University of Georgia who surveyed farmers across the state, there are feral hogs present in every county. This puts the more than 10 million acres of farmland across the state, and almost 1.5 million acres in Northeast Georgia alone at risk.

Farmers across the state are having to take measures into their own hands. In his survey, Mengak found 47.7% of those surveyed did not seek outside help, usually shooting feral hogs on sight. Of those who did seek outside help, nearly 70% sourced outside help from “other,” meaning they sought out family, friends and neighbors to help them deal with the problem, usually in the form of organized hunting expeditions, which is known to be largely ineffective.

What has been proven to be effective is systematic trapping. These are large corral traps set up on the perimeter of farms. They are big enough to trap whole sounders, or groups, of hogs, usually 6 to 20 individuals. The goal is to trap the entire sounder at once, otherwise the hogs will learn to avoid the trap in the future. To achieve this, remote cameras are set up to record the area, and farmers are able to remotely trigger the door to drop.

The problem is that this approach takes a lot of effort, time and patience. According to Boyce, most nights only half of the sounder will go in. This leaves the farmer with a choice: capture half now, or wait. If they capture half of the sounder, the other half will be back, and they will be more hesitant to go inside of the trap.

Not to mention the cost. A study from the National Wildlife Research Center, found that in Georgia alone, the cost of trapping totaled $130,300 in 2014. Across the 11 states they looked at, trapping totaled nearly $692,000.

So Willie McNabb’s tweet rang partly true, albeit exaggerated. Feral hogs are a problem across Georgia and the Southeast U.S., but there is some hope in the near future. Yet, for now, most farmers are stuck dealing with the growing populations of hogs on their own, which doesn’t come cheap.

Billy Wright is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)