Kate Van Cantfort likes her feet to be in work boots and her face to be makeup free. What she wants is to be able to support herself and her 11-year-old daughter, Emma Van Cantfort-Carpenter.

But lately, the 41-year-old owner of Lotta Mae’s Supply Co., a home and garden store once located close to the train tracks on Barber Street, keeps all of the store’s inventory in her house and two storage units. As of February 2019, she lost the lease on the store where Emma used to flatten coins when trains came by.

At first, Van Cantfort did not realize the grief she felt when the landlord canceled her lease, leaving her 10 days to pack up the store she created in July 2017 with $30,000. “It is so heart upsetting for me,” Van Cantfort says about visiting her storage units that smell like Lotta Mae’s used to.

Van Cantfort is an example of a growing number of women who are opening up their own businesses. Every day between 2017 and 2018, 1,821 women-owned businesses opened, according to The 2018 State of Women-Owned Businesses Report by American Express. That was up from the previous year’s report, in which the net number of women owned businesses was 827.

Van Cantfort is also one of millions of single mothers in the South who contributes to all or a portion of their family’s income. As the number of women-owned businesses slowly increases, Van Cantfort remains positive despite the loss of her store’s physical location. In the meantime, she continues to develop her store’s online presence as well as hosting pop-up shops.

In February 2019, Van Cantfort posted on her website to alert her customers of the change in plans and location. “Sometimes we end up where we planned to arrive,” she wrote. “Sometimes. Often we arrive in a new destination – stretched and maybe worn – and yet, enriched. This is how it has been with the shop.”

Another business, RentPost, now runs out of her old space.

Hard Times Came for Van Cantfort

Forty percent of businesses are now either owned by a woman, or a woman owns at least 51% of the company, according to the American Express report. The state of Georgia ranks eighth in the nation for the most increased economic clout by women-owned businesses from 2007 to 2018, the report said. Economic clout is the increase in the number of firms as well as the increase in employment and revenue.

Despite the increase in the number of women who own businesses, these companies make up only 8% of employment in the private sector and 4.3% of total revenue in the U.S., the report said.

And women still face many difficulties when starting a business. For Van Cantfort, these struggles stem from the fact that she is both a business owner and a single mom.

An estimated 11.3 million family homes have children under the age of 18, according to The Status of Women in the South, a report published in 2016 by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. It included data from a dozen states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as the District of Columbia. Single mothers led 3.1 million of these homes. Women were the sole provider or contribute to 40% of family income in half of the 11.3 million households, the data showed.

This is true for Van Cantfort as she is the sole source of income for herself and her daughter. She says that she does not receive child support. She only receives money from her first ex-husband, Tracy Carpenter, when he thinks about it − which happens sporadically.

Think about the amount of money that little business generated that went into other things,” Van Cantfort said. “Any other business owner that I know, particularly a woman, has a partner, usually a man, who’s helping to pay the cost of living expenses.”

To make matters worse, Van Cantfort lost nearly everything following her second divorce in 2018. These losses include her premarital and cash assets, several family heirlooms, even the baby books for her only child. She lost the houses in Kansas, and her second ex-husband, who she asked to remain anonymous, put the farmhouse he bought her up for sale.

How It All Came to Be

While Van Cantfort’s is not the typical southern, agricultural family story, her ancestry and heritage were part of her inspiration to start this business. The store is named after her great-great-grandmother’s aunt, Lotta, for her adventurous spirit and her great-grandmother, Mae, a popular family name.

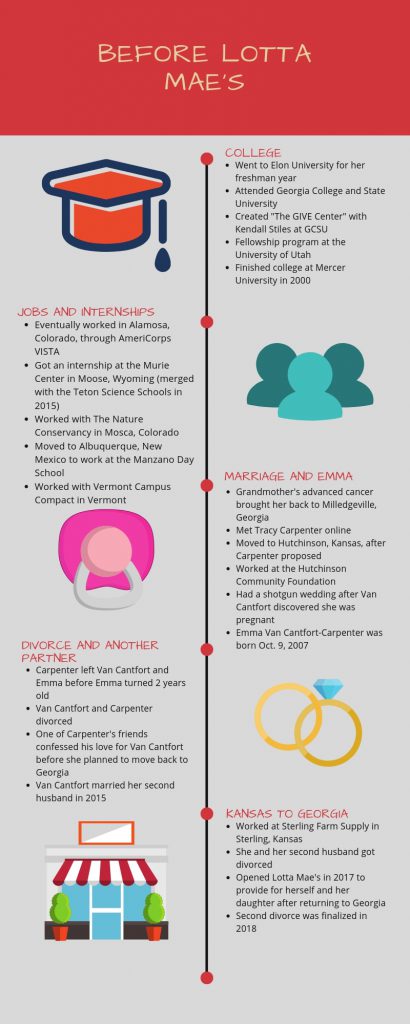

Van Cantfort was born in Kingstree, South Carolina, on Sept. 8, 1977, and later moved to several small towns in Georgia, including McRae, Gordon, LaGrange, Milledgeville, Jesup and back to Milledgeville.

After living in small town after small town, Van Cantfort jokingly calls herself the “queen of nowhere.” She thought she was “highfalutin” when her grandfather took her to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

Small town living influenced Van Cantfort to make her store welcoming and community-minded. She also learned to connect customers with other local businesses in order to meet the customers’ needs.

The path to opening this business was not straightforward for Van Cantfort. After she graduated from Mercer University in 2000, she said, “I gotta save the world.” She alternated working in social work and environmental work for several years.

Van Cantfort later moved to Kansas, married Emma’s father, Carpenter and gave birth to Emma. After they divorced, she began dating a man whose family owned Sterling Farm Supply in Sterling, Kansas. They would get married years later. She sold plants, seeds and other items out of the farm supply headquarters. This was the first iteration of Lotta Mae’s, though at the time, that was not the shop’s name.

The Little Store That Could

After her second divorce, Van Cantfort opened the next iteration of her home and garden store, Lotta Mae’s Supply Co., on July 16, 2017, to provide for herself and Emma.

The first day, she expected to be open for four hours and did not plan to have many visitors. But people lined up at the door, forcing her to keep the shop open for six hours. For a time, the store was doing well.“This little engine has been just busting tail,” Van Cantfort says.

Looking back on the days at Barber Street, two customers of Lotta Mae’s, Tori Hiel and Curtis Jester, both say that Van Cantfort brought in local goods and made a point to talk to her customers.

Jester says that he went to the store about twice a month, sometimes “just to chat.” Karol Patterson, a vendor and customer at Lotta Mae’s, says that the inventory surprised her. The items were somewhat expensive yet rare enough that customers did not mind the cost.

Van Cantfort’s close relationship with her customers and her daughter is evident, even when the future is not. This mother-daughter duo is separated by 30 years, one month and one day.

“She is definitely Kate’s [Van Cantfort’s] priority in life. And their unique, loving interaction is to be envied,” Patterson says.

Losing the shop was hard for little Emma as well. Lotta Mae’s was like the sibling she never had. Selling the new inventory was like “changing a baby’s diaper.” Emma just did not like to water the plants.

While the future of the business and Van Cantfort’s income is uncertain, she continues to fulfill online orders from customers. She recently held a pop-up shop in Washington, Georgia, and plans to host another in Brunswick, Georgia, on May 10-11.

Outside of their rental house in Athens, Van Cantfort faces Emma as they discuss the store and the future. She holds each side of her cardigan sweater in her hands and wraps one side over the other, crossing her arms at the same time.

Between the laughter, the fond memories and the hopeful ideas for what the future could hold, Van Cantfort’s voice begins to choke up. Emma looks at her mom and says that if she wants to reopen Lotta Mae’s, “You’d have my full support.”

With those words, the self-proclaimed “queen of nowhere” tries to hide the tear that starts to run down her left cheek.

Mary Martin Harper is a junior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.